The question of “what was Africa called before” the adoption of its modern name is not merely a linguistic curiosity; it is a gateway into a complex history of geography, civilization, and the evolution of human settlement. While historical texts point to names like Alkebulan, Ethiopia, or Libya, modern Tech & Innovation has provided a new lens through which we can verify these ancient claims. Through the use of advanced remote sensing, autonomous mapping, and AI-driven geospatial analysis, researchers are now able to reconstruct the physical and political landscapes of the continent as they existed thousands of years ago.

This article explores how modern innovation—specifically within the realm of mapping and remote sensing—is being used to bridge the gap between ancient nomenclature and physical reality, uncovering the hidden structures of the civilizations that defined the continent long before the name “Africa” became the global standard.

The Evolution of Continental Mapping: From Alkebulan to Remote Sensing

To understand what the continent was called before, we must look at the oldest surviving records. Many historians suggest that Alkebulan is the oldest name of indigenous origin, meaning “mother of mankind” or “garden of Eden.” However, verifying the extent of the civilizations that used this name requires more than just oral tradition; it requires precise mapping of ancient land use and migratory patterns.

Understanding Alkebulan and Ancient Cartography

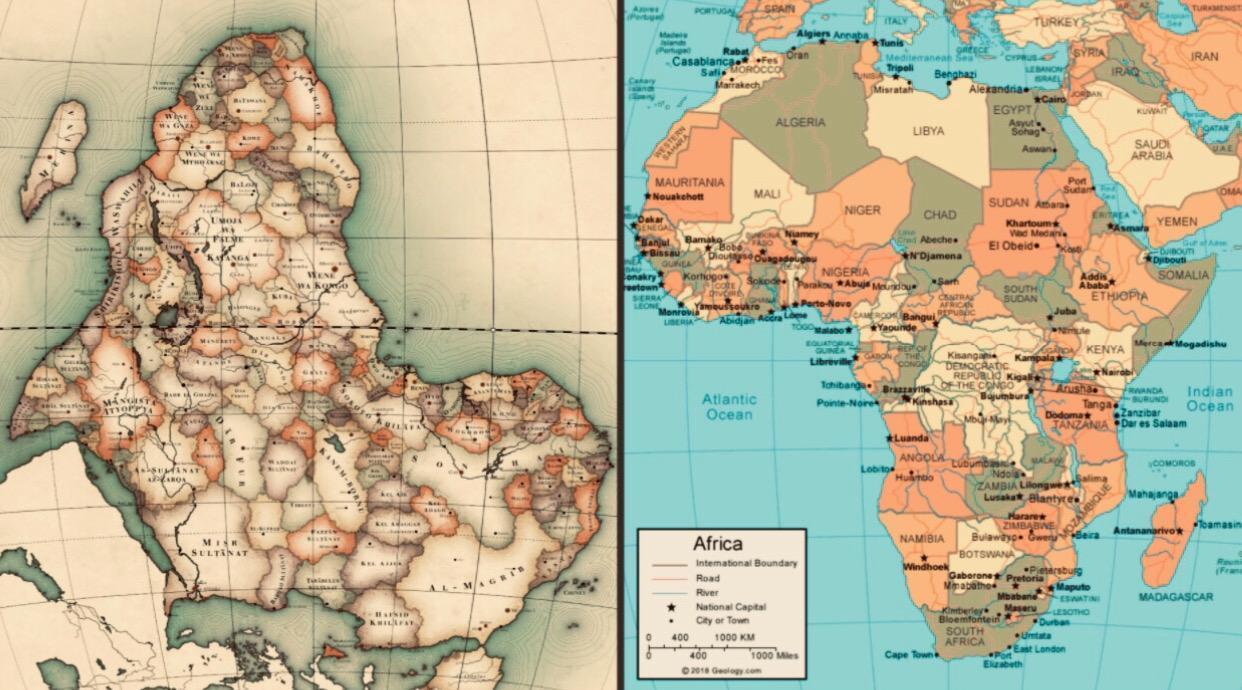

The transition from Alkebulan to the Roman-influenced Africa represents a shift in how the world viewed the continent’s boundaries. Ancient cartography was often limited by the physical reach of explorers. Today, mapping innovation has moved beyond the “edge of the world” mentality. By using multispectral imaging from orbital and aerial platforms, tech-innovators can identify ancient trade routes and agricultural systems that suggest a much more interconnected continent than previously thought. These digital maps allow us to see the “Alkebulan” era not as a collection of isolated tribes, but as a sophisticated network of kingdoms with defined boundaries.

The Role of Satellite Imagery vs. High-Resolution Drone Mapping

While satellite imagery provides a macro-view of the continent, it often lacks the resolution required to identify specific archaeological features. Innovation in high-resolution drone mapping has filled this gap. By deploying Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) equipped with Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) positioning, researchers can create maps with centimeter-level accuracy. This technology allows us to visualize the footprints of ancient cities that existed when the continent was known by its various regional names, such as Kush or Punt, providing a technical foundation for historical claims.

Remote Sensing: Redefining Archaeological Discovery in the Saharan and Sub-Saharan Regions

One of the greatest challenges in answering “what was Africa called before” is that many of the physical records are buried under the shifting sands of the Sahara or the dense canopies of the equatorial rainforests. Remote sensing technology has become the primary tool for bypassing these environmental obstacles.

LiDAR Technology: Seeing Through the Vegetation

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is perhaps the most significant innovation in the field of remote sensing over the last decade. By firing thousands of laser pulses per second at the ground and measuring the time it takes for them to bounce back, LiDAR can create a highly detailed 3D map of the terrain (a “point cloud”). In regions like the Bight of Benin or the dense forests of Central Africa, LiDAR can “strip away” the digital representation of trees to reveal the ruins of ancient earthworks and structures beneath. These findings often correlate with ancient names for these regions, proving that the “pre-Africa” era was one of high urban density and complex engineering.

Photogrammetry and 3D Reconstruction of Ancient Sites

Once a site is identified through LiDAR, photogrammetry is used to create immersive 3D models. By taking hundreds of high-resolution images from different angles and processing them through sophisticated software like Pix4D or Agisoft Metashape, innovators can reconstruct ancient ruins with photographic textures. This allows historians to “walk through” the kingdoms of the past. These reconstructions provide a visual context to the names found in ancient texts, such as the legendary “Land of the Spirits” or “Ta-Neter,” terms used by the Egyptians to describe the coastal regions of East Africa.

Mapping Lost Civilizations: Tech-Driven Insights into Pre-Colonial Names

The nomenclature of the continent was historically divided into powerful regional empires. Mapping technology is now being used to define the exact borders of these entities, providing a clearer picture of the geopolitical landscape before the colonial era.

The Kingdom of Kush and the Nubian Survey Tech

In the northern regions, what we now call Sudan was once the heart of the Kingdom of Kush. Modern tech-driven surveys use Magnetometry and Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to identify buried temples and pyramids without ever breaking the soil. These innovations allow researchers to map the “Kushite” influence across the Nile Valley. By integrating this geophysical data with topographical maps, we can see how the environmental tech of the time—such as “haffirs” (water reservoirs)—supported a civilization that rivaled Egypt, giving physical weight to the name “Kush” as a primary identifier for the region.

Uncovering the Walls of Benin through Autonomous Flight Data

The Walls of Benin were once one of the largest man-made structures in the world, yet much of their extent was lost to time and forest overgrowth. Autonomous flight technology, combined with AI-pathfinding, allows drones to map these walls in areas that are inaccessible to humans. The data collected reveals a massive network of linear earthworks that define the Edo civilization. This mapping innovation proves that the “Benin” identity was a sophisticated territorial state long before the continent was aggregated under a single name by European cartographers.

The Future of Aerial Innovation in Preserving African Heritage

As we look toward the future, the technology used to explore the past is becoming more accessible and intelligent. The question of “what was Africa called before” is being answered by a new generation of African tech innovators using AI and remote sensing to reclaim their own history.

AI-Driven Feature Recognition in Remote Landscapes

The sheer volume of data produced by remote sensing is too vast for human analysis alone. AI and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms are now being trained to recognize specific patterns in the landscape—such as the circular foundations of ancient dwellings or the tell-tale signs of ancient irrigation furrows. These AI models can scan thousands of square miles of satellite and drone data in hours, identifying potential archaeological sites that have been “hidden in plain sight” for centuries. This tech is uncovering the physical reality of the “Alkebulan” era at an unprecedented pace.

Open-Source Geospatial Data and Local Innovation Hubs

One of the most exciting trends in mapping innovation is the democratization of data. Platforms like OpenStreetMap and the use of open-source GIS (Geographic Information Systems) software are allowing local universities across the continent to lead their own mapping projects. By combining local oral histories (the traditional names of the land) with modern geospatial data, these hubs are creating a “living map” of the continent. This innovation ensures that the answer to “what Africa was called before” is informed by the people who live there, supported by the most advanced technology available.

Conclusion: Tech as a Bridge to the Past

The inquiry into “what was Africa called before” is a journey through time that is increasingly being paved by technological innovation. From the use of LiDAR to penetrate the deepest jungles to the application of AI in identifying ancient urban centers, remote sensing and mapping are doing more than just creating charts—they are reconstructing an identity.

By moving beyond the limitations of traditional archaeology and using the tools of the 21st century, we are discovering that the continent was a tapestry of sophisticated names and cultures—Alkebulan, Kush, Punt, Ethiopia, and many others—each with a defined geographic footprint that can now be measured, modeled, and preserved. This fusion of history and technology does not just tell us what the continent was called; it shows us how it lived, how it thrived, and how it continues to innovate into the future. Through mapping and remote sensing, we are finally seeing the continent’s past in high definition, honoring the legacy of the many names that came before “Africa.”