The concept of an “interval” is fundamental in mathematics, providing a precise way to describe a range of numbers. Whether you’re dealing with real numbers on a number line, sets of solutions to equations, or the domain and range of functions, understanding intervals is crucial for clear and concise mathematical communication. In essence, an interval represents a contiguous subset of the real numbers, meaning all the numbers between two endpoints, inclusive or exclusive of those endpoints. This article delves into the definition, notation, types, and common applications of intervals in mathematics.

Understanding the Building Blocks of Intervals

At its core, an interval is defined by two real numbers, which we call the endpoints. These endpoints dictate the boundaries of the set of numbers included. However, the nature of these boundaries – whether they are included in the interval or not – leads to different types of intervals.

Endpoints and Their Significance

The two numbers that define an interval are its lower bound and its upper bound. The lower bound is the smallest number in the interval, and the upper bound is the largest. For example, in the interval from 2 to 5, 2 is the lower bound and 5 is the upper bound. The numbers within the interval are all the real numbers that fall between these two values.

The distinction between whether these endpoints are themselves part of the interval is critical. This leads to the classification of intervals into open, closed, and half-open (or half-closed) types. The type of interval dictates how we interpret the mathematical statements involving that interval.

Number Lines as Visual Representations

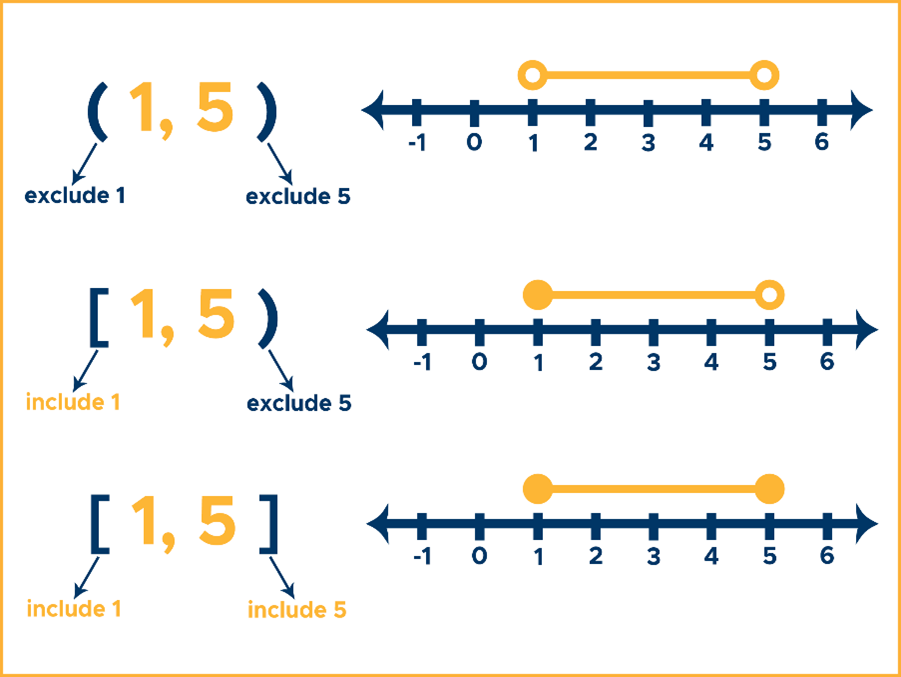

One of the most intuitive ways to visualize intervals is by using a number line. A number line is a straight line with numbers placed at equal intervals along its length. We can represent intervals on this line using different notations. Typically, open endpoints are indicated by an unfilled circle or a parenthesis, while closed endpoints are shown with a filled circle or a square bracket. This visual aid helps in grasping the concept of a continuous range of numbers and the inclusion or exclusion of boundary values.

For example, to represent the interval from 2 to 5 on a number line:

- If it’s a closed interval (including 2 and 5), we would place filled circles at 2 and 5 and shade the line segment between them.

- If it’s an open interval (excluding 2 and 5), we would use unfilled circles at 2 and 5 and shade the line segment between them.

- If it’s half-open, one endpoint would have a filled circle, and the other an unfilled circle.

Types of Intervals and Their Notations

Mathematical notation provides a concise and universally understood way to represent intervals. These notations are essential for accurately conveying information about ranges of numbers in equations, inequalities, and function definitions.

Open Intervals: Excluding the Endpoints

An open interval contains all real numbers between two given numbers, but it does not include the endpoints themselves. If $a$ and $b$ are real numbers such that $a < b$, the open interval between $a$ and $b$ is denoted by $(a, b)$. This notation signifies that any number $x$ such that $a < x < b$ belongs to this interval.

On a number line, an open interval $(a, b)$ is represented by a line segment between $a$ and $b$ with open circles at $a$ and $b$. For example, the interval $(2, 5)$ includes all numbers greater than 2 and less than 5, such as 2.1, 3, 4.99, but not 2 or 5 themselves.

Closed Intervals: Including the Endpoints

A closed interval contains all real numbers between two given numbers, and it does include the endpoints. If $a$ and $b$ are real numbers such that $a < b$, the closed interval between $a$ and $b$ is denoted by $[a, b]$. This notation signifies that any number $x$ such that $a le x le b$ belongs to this interval.

On a number line, a closed interval $[a, b]$ is represented by a line segment between $a$ and $b$ with filled circles at $a$ and $b$. For example, the interval $[2, 5]$ includes all numbers greater than or equal to 2 and less than or equal to 5, including 2 and 5.

Half-Open (or Half-Closed) Intervals: One Endpoint Included

Half-open intervals (also known as half-closed intervals) include one endpoint but exclude the other. There are two types:

- Left-open, right-closed interval: This interval includes all real numbers between $a$ and $b$, including $b$ but not $a$. It is denoted by $(a, b]$ and represents numbers $x$ such that $a < x le b$.

- Left-closed, right-open interval: This interval includes all real numbers between $a$ and $b$, including $a$ but not $b$. It is denoted by $[a, b)$ and represents numbers $x$ such that $a le x < b$.

On a number line, $(a, b]$ is shown with an open circle at $a$ and a filled circle at $b$, while $[a, b)$ has a filled circle at $a$ and an open circle at $b$. For instance, the interval $[2, 5)$ includes numbers from 2 up to, but not including, 5. The interval $(2, 5]$ includes numbers greater than 2 up to and including 5.

Infinite Intervals: Extending Beyond Finite Bounds

Not all intervals are bounded by two finite numbers. Infinite intervals extend indefinitely in one or both directions on the number line. These are crucial for describing the behavior of functions or the solutions to certain types of inequalities.

Intervals Extending to Infinity

An infinite interval that is bounded from below but extends indefinitely upwards is denoted using the symbol for infinity ($infty$).

- Left-unbounded, right-closed interval: $[a, infty)$ represents all real numbers $x$ such that $x ge a$. The parenthesis before $infty$ is because infinity is not a number that can be included.

- Left-unbounded, right-open interval: $(a, infty)$ represents all real numbers $x$ such that $x > a$.

- Left-closed, right-unbounded interval: $(-infty, b]$ represents all real numbers $x$ such that $x le b$. The parenthesis before $-infty$ is standard.

- Left-open, right-unbounded interval: $(-infty, b)$ represents all real numbers $x$ such that $x < b$.

On a number line, these intervals are represented by shading the line from the finite endpoint (with an appropriate circle) extending infinitely to the right or left, usually indicated by an arrow.

The Entire Real Number Line

The entire set of real numbers is also considered an interval, denoted by $(-infty, infty)$. This encompasses all possible real numbers, from negative infinity to positive infinity.

Applications of Intervals in Mathematics

The concept of intervals is not merely an abstract mathematical construct; it has profound practical applications across various branches of mathematics and its related fields.

Solving Inequalities

One of the most direct applications of intervals is in expressing the solution sets of inequalities. For instance, consider the inequality $2x + 3 < 7$.

- Subtract 3 from both sides: $2x < 4$.

- Divide by 2: $x < 2$.

The solution set for this inequality is all real numbers less than 2. In interval notation, this is represented as $(-infty, 2)$.

Similarly, the inequality $x^2 – 4 ge 0$ can be solved by factoring: $(x-2)(x+2) ge 0$. This inequality holds true when both factors are non-negative or both are non-positive.

- Case 1: $x-2 ge 0$ and $x+2 ge 0 implies x ge 2$ and $x ge -2$. The intersection is $x ge 2$, which is $[2, infty)$.

- Case 2: $x-2 le 0$ and $x+2 le 0 implies x le 2$ and $x le -2$. The intersection is $x le -2$, which is $(-infty, -2]$.

The complete solution set is the union of these two intervals: $(-infty, -2] cup [2, infty)$.

Domains and Ranges of Functions

In calculus and pre-calculus, intervals are essential for defining the domain and range of functions. The domain of a function is the set of all possible input values (x-values) for which the function is defined. The range is the set of all possible output values (y-values) that the function can produce. These sets are frequently expressed using interval notation.

For example, consider the function $f(x) = sqrt{x-3}$. For the function to be defined, the expression under the square root must be non-negative. Therefore, $x-3 ge 0$, which means $x ge 3$. The domain of this function is $[3, infty)$. The range of this function (assuming it produces real numbers) is $[0, infty)$, as the square root of a non-negative number yields a non-negative number.

Another example, $g(x) = frac{1}{x-1}$, has a domain that excludes any value of $x$ that makes the denominator zero. So, $x-1 neq 0$, which means $x neq 1$. The domain can be expressed as the union of two intervals: $(-infty, 1) cup (1, infty)$. The range of this function is also $(-infty, 0) cup (0, infty)$, as the reciprocal of any non-zero number is also non-zero.

Set Theory and Interval Arithmetic

Intervals are a fundamental concept in set theory. Operations on sets, such as union, intersection, and complement, can be applied to intervals. For instance, the intersection of two intervals represents the numbers that are common to both. If we have interval A = [1, 5] and interval B = [3, 7], their intersection is [3, 5]. Their union, A $cup$ B, would be [1, 7].

Interval arithmetic is a branch of numerical analysis that deals with the computation of intervals rather than single numbers. This is particularly useful in situations where uncertainty exists, such as in computer programming or when dealing with measurements. Instead of a single value, an interval represents a range of possible values. Operations are then performed on these intervals to produce a resulting interval that bounds the true result.

Other Mathematical Fields

The utility of intervals extends to other areas like:

- Probability: Describing the probability of an event falling within a certain range of values.

- Analysis: Defining convergence of sequences and series, and describing regions of continuity or differentiability for functions.

- Topology: Understanding connectedness and compactness of topological spaces.

In conclusion, the interval is a versatile and indispensable concept in mathematics. Its clear notation and ability to represent ranges of numbers make it a cornerstone for expressing solutions to inequalities, defining the scope of functions, and performing operations in set theory and beyond. Mastering the understanding of different interval types and their notations is a crucial step in developing a strong foundation in mathematical reasoning and problem-solving.