In an increasingly interconnected world driven by technology and innovation, the concept of time synchronization transcends mere convenience; it is the fundamental backbone enabling global operations, accurate data exchange, and the seamless functioning of complex systems. At the heart of this global temporal coordination lies Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), a term that, while historically significant, has evolved into its modern iteration: Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Understanding GMT and its derivatives is not just an academic exercise; it’s essential for anyone involved in developing, managing, or utilizing technology on a global scale. From the precise flight paths of autonomous drones to the timestamping of critical financial transactions and the orchestration of distributed AI systems, a universal standard for time is indispensable.

The Universal Synchronizer: Demystifying GMT and Its Evolution to UTC

To truly grasp the importance of GMT in the realm of tech and innovation, we must first understand its origins and its relationship with the modern standard, UTC. The need for a universal time standard became evident with the advent of rapid communication and transportation methods in the 19th century.

From Greenwich Meridian to Global Standard

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) originated from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London. Established in 1675, the observatory played a crucial role in naval navigation, as sailors needed accurate time to calculate their longitude at sea. By the late 19th century, with the expansion of railways and international trade, the need for a standardized time system became paramount. In 1884, at the International Meridian Conference in Washington, D.C., the Greenwich Meridian was adopted as the Prime Meridian (0° longitude), and GMT was chosen as the world’s standard time. This decision provided a single reference point for timekeeping across the globe, facilitating international shipping, telegraphy, and later, aviation.

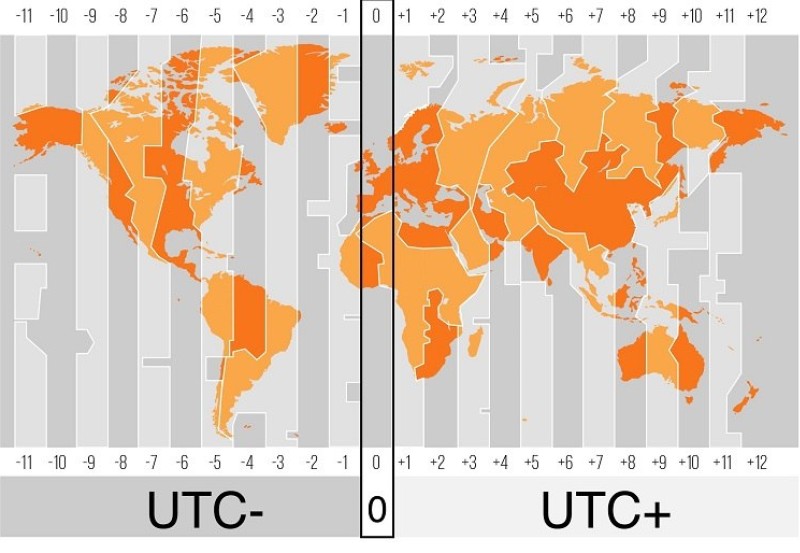

GMT was initially defined astronomically, based on the rotation of the Earth relative to the sun. Specifically, it was the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory. For many decades, GMT served as the primary civil time standard for much of the world, acting as the zero-point for all other time zones. For instance, a time zone might be described as GMT+1 or GMT-5, indicating its offset from Greenwich.

The Transition to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

While GMT served its purpose admirably for a long time, the increasing precision requirements of modern science and technology, particularly in fields like atomic physics and space exploration, exposed its limitations. Earth’s rotation is not perfectly uniform; it experiences tiny, unpredictable fluctuations and a gradual slowing down. Relying solely on astronomical observations for timekeeping was no longer precise enough for systems requiring accuracy down to microseconds or even nanoseconds.

This led to the development of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) in 1960 and its formal adoption in 1972. UTC is based on International Atomic Time (TAI), which is a highly stable, uniform time scale derived from a weighted average of the readings of atomic clocks around the world. To keep UTC aligned with the Earth’s less uniform rotation (and thus with local solar time), leap seconds are occasionally added or subtracted from UTC. This ensures that UTC remains within 0.9 seconds of UT1 (a form of GMT based on astronomical observation).

Crucially, from a practical standpoint, UTC is effectively the same as GMT for most everyday purposes and many technical applications. The time zone offsets are typically measured from UTC (e.g., UTC+1, UTC-5). However, for high-precision technical applications, especially in navigation, satellite communication, and advanced computing, UTC is the universally recognized and preferred standard. When you see “GMT” in a modern technological context, it’s often used colloquially to refer to UTC.

Why GMT/UTC Remains Crucial for Modern Systems

The shift from an astronomically defined GMT to an atomic-clock-driven UTC represents a profound leap in timekeeping precision, directly impacting the capabilities and reliability of modern technology. Without a consistent, highly accurate global time standard like UTC, the intricate web of digital systems that define our modern world would quickly unravel. It provides the single, unambiguous reference necessary for coordinating events across vast geographical distances and diverse technological platforms.

The Backbone of Digital Operations: GMT in Data, Networks, and AI

In the digital age, time is not merely a sequence of events but a critical metadata point, an ordering principle, and a synchronizing agent that underpins nearly every technological endeavor. The consistent application of GMT/UTC ensures integrity, coherence, and functionality.

Timestamping and Data Integrity

Every digital event—from creating a file, sending an email, making a database entry, or logging sensor data—is typically associated with a timestamp. When these systems operate across different geographical locations, using local time zones for timestamps would lead to confusion, ambiguity, and potential data corruption. For example, if a data log shows an event occurred at “08:00,” was that 08:00 AM in New York, London, or Tokyo? Using UTC for all internal timestamps eliminates this ambiguity.

This consistency is vital for:

- Auditing and Forensics: In cybersecurity, financial transactions, or regulatory compliance, precise, unambiguous timestamps are crucial for reconstructing event sequences and identifying anomalies.

- Data Aggregation and Analysis: When combining data from multiple sources worldwide, UTC timestamps ensure that events are correctly ordered chronologically, which is essential for accurate analytics, time-series analysis, and trend identification in big data applications.

- Software Versioning and Collaboration: In software development, version control systems rely on timestamps to track changes and merge contributions from developers working in different parts of the world.

Network Synchronization and Distributed Systems

Modern computing relies heavily on distributed systems and global networks. Servers, databases, and services are often spread across continents, yet they must function as a cohesive unit. Network Time Protocol (NTP) is a standard protocol used to synchronize computer system clocks over a network, and it typically references UTC.

Without accurate time synchronization via NTP, using a UTC reference:

- Data Inconsistencies: Transactions or updates might be processed out of order, leading to corrupted data in distributed databases or inconsistent states across networked services.

- Authentication Failures: Many security protocols (e.g., Kerberos) rely on closely synchronized clocks between client and server; desynchronization can lead to failed authentications.

- Fault Tolerance Issues: In high-availability systems, correct timestamping is critical for determining the order of events when recovering from failures or coordinating failovers.

- Real-time Applications: Video conferencing, live streaming, and online gaming depend on synchronized clocks for a smooth, lag-free user experience.

AI, Machine Learning, and Time-Series Analysis

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning models frequently operate on vast datasets, many of which are time-series data—data points indexed in time order. This includes everything from sensor readings in an IoT network, stock market fluctuations, energy consumption patterns, to user interaction logs.

- Model Training and Inference: For AI models to accurately learn patterns and make predictions based on temporal sequences, the input data must be chronologically sound. UTC timestamps ensure that the sequence is unambiguous, regardless of where the data was collected.

- Real-time Anomaly Detection: In fraud detection, predictive maintenance, or cybersecurity, AI systems monitor continuous streams of data. UTC synchronization is critical for correlating events from diverse sources and detecting anomalies in real-time.

- Autonomous Decision-Making: For systems like self-driving cars or industrial robots that rely on AI for decision-making, correlating sensor inputs (camera, radar, lidar) with precise timestamps (often in UTC) is non-negotiable for accurate perception and safe operation.

Cybersecurity and Event Logging

In the critical domain of cybersecurity, accurate and universally referenced timestamps are not just important; they are indispensable. Every security-relevant event, from a failed login attempt to a network intrusion alert, is logged with a timestamp.

- Attack Reconstruction: When analyzing a security incident, investigators piece together a timeline of events from logs across multiple systems, servers, and network devices. If these logs use different local times or are not accurately synchronized to UTC, reconstructing the attack chain becomes incredibly difficult, if not impossible.

- Regulatory Compliance: Many industry regulations (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA) require robust auditing and logging capabilities, often specifying the use of a universal time standard to ensure data integrity and traceability for legal and compliance purposes.

- Threat Intelligence: Sharing threat intelligence across organizations and national borders relies on a common time reference to correlate attack indicators and patterns effectively.

Precision Timing for Autonomous Systems and IoT Ecosystems

The rise of autonomous systems and the Internet of Things (IoT) marks a new frontier for technology, where the coordination of countless devices and the execution of complex tasks without human intervention are paramount. Here, the precision offered by UTC is absolutely critical.

Drones and Robotics: Synchronized Navigation and Sensor Fusion

For drones (UAVs), autonomous vehicles, and sophisticated robotics, precise time synchronization is a cornerstone of their operation.

- Flight Planning and Mission Execution: Pre-programmed flight paths, waypoints, and mission commands are often time-stamped. Coordinating multiple drones in a swarm or synchronizing their actions requires a common time reference (UTC) to ensure they operate in harmony, avoid collisions, and execute tasks at the right moments.

- Sensor Fusion: Autonomous systems integrate data from a multitude of sensors: GPS, IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units), cameras, lidar, radar, and more. To create an accurate, real-time understanding of their environment, the data from these disparate sensors must be fused. This fusion process is highly dependent on precise timestamps, typically in UTC, to correctly align sensor readings taken at slightly different moments. Even minuscule timing errors can lead to significant positional or environmental misinterpretations, jeopardizing safety and mission success.

- Data Logging for Post-Analysis: For regulatory compliance, incident investigation, or performance optimization, flight data recorders and drone logs timestamp every event, sensor reading, and control input. UTC ensures these logs are unambiguous for later analysis, regardless of where the drone operated.

Smart Cities and IoT: Orchestrating Interconnected Devices

Smart cities and vast IoT ecosystems involve millions of interconnected devices, from smart traffic lights and environmental sensors to utility meters and security cameras.

- Event Correlation: In a smart city, a traffic sensor detects congestion, a public transport system adjusts schedules, and an emergency service is dispatched. Correlating these events from different systems requires a universal time standard. Without UTC, understanding the sequence and cause-and-effect relationships between these events would be nearly impossible.

- Resource Management: Energy grids use smart meters and sensors to optimize distribution and consumption. Precise UTC timestamps allow for accurate load balancing and demand-response management across vast, distributed networks.

- Predictive Maintenance: IoT sensors on infrastructure or machinery continuously collect data. UTC timestamps are crucial for building accurate time-series models to predict failures and schedule maintenance proactively.

Satellite Technology and Geospatial Data

Satellite systems, including GPS (Global Positioning System), GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou, are inherently reliant on extremely precise timekeeping.

- GPS Operation: GPS receivers calculate their position by measuring the time delay of signals received from multiple satellites. Each satellite transmits its precise location and an atomic clock timestamp. The difference between the time the signal was sent and the time it was received allows the receiver to determine its distance from the satellite. This entire system relies on all satellite clocks and the receiver clock being synchronized to an extremely high degree of accuracy, typically based on UTC, to achieve centimeter-level precision.

- Earth Observation and Remote Sensing: Satellites collecting imagery, weather data, or environmental measurements timestamp their observations in UTC. This is crucial for correlating data from different satellite passes, other sensors, or ground truth measurements, enabling accurate mapping, climate modeling, and disaster response.

Facilitating Global Innovation: Collaboration Across Time Zones

Innovation thrives on collaboration, and in today’s globalized landscape, teams are often distributed across continents. UTC serves as the silent facilitator, bridging geographical divides and ensuring smooth, efficient teamwork.

Software Development and DevOps Workflows

The software industry is a prime example of global collaboration. Development teams, testing teams, and operations teams can be spread across multiple time zones.

- Version Control Systems: Tools like Git rely heavily on timestamps for commit history, merges, and resolving conflicts. Consistent UTC timestamps ensure that the sequence of changes is unambiguous, regardless of the developer’s location.

- Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD): Automated build and deployment pipelines depend on accurate event logging and scheduling. UTC timestamps prevent ambiguity when tracking deployments across different environments or coordinating releases.

- Meeting Scheduling: While seemingly mundane, scheduling virtual meetings and agile ceremonies across diverse time zones is made infinitely easier by having a common reference point like UTC, allowing participants to easily convert to their local time.

International Research and Development Projects

Large-scale scientific and technological research often involves international consortia. From particle accelerators to space telescopes and climate modeling initiatives, collaboration on massive datasets and complex experiments requires universal time.

- Experiment Coordination: Synchronizing experiments performed in different labs around the world, or correlating data collected by globally distributed sensor networks (e.g., seismic sensors, astronomical observatories), demands precise UTC timestamps.

- Data Archiving and Sharing: Research data repositories adopt UTC as the standard for timestamps, ensuring that data contributed by various institutions is consistently cataloged and easily retrievable for future analysis.

Cloud Computing and Global Infrastructure

Cloud providers like AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud operate massive data centers worldwide. Their services—compute instances, databases, storage—are designed to be globally accessible and highly available.

- Load Balancing and Geo-Replication: Distributing user requests and replicating data across different regions for performance and redundancy requires accurate time synchronization. UTC ensures that different nodes in the cloud infrastructure have a consistent view of time, preventing data conflicts and ensuring seamless service delivery.

- Serverless Computing: Functions triggered by events in a serverless architecture rely on event timestamps. UTC provides the consistent context for these event-driven operations.

- Monitoring and Logging: Cloud monitoring tools aggregate logs and metrics from thousands of servers and services globally. Consistent UTC timestamps are crucial for creating a coherent picture of system health and performance across the entire cloud ecosystem.

Future Forward: The Continuing Relevance of Universal Time Standards

As technology advances, the demand for even greater precision and reliability in timekeeping will only intensify. The principles behind GMT and UTC will remain foundational, though the methods of achieving and distributing them will continue to evolve.

Challenges in Time Synchronization at Scale

Despite the robust nature of UTC and protocols like NTP, challenges persist, especially with the proliferation of edge devices, highly distributed systems, and real-time demands.

- Network Latency and Jitter: Achieving microsecond-level synchronization across vast, unpredictable networks remains a challenge due to varying network latencies and jitter.

- Resource Constraints: Small, low-power IoT devices may have limited processing power or battery life, making it difficult to implement sophisticated time synchronization protocols.

- Security Vulnerabilities: NTP, like any network protocol, can be susceptible to attacks, making secure time synchronization a continuous area of research and development.

Atomic Clocks and Future Precision

The relentless pursuit of precision continues. New generations of atomic clocks, including optical atomic clocks, promise even greater accuracy, potentially leading to future revisions or refinements of UTC. These advancements are not merely academic; they unlock new possibilities in fundamental physics research, ultra-precise navigation (e.g., next-generation GPS), and even quantum computing.

The Human Element: Bridging Universal Time with Local Experience

While UTC is the undisputed standard for machines and global operations, humans still operate primarily within their local time zones. The seamless conversion between UTC and local time is a critical user experience challenge for developers. User interfaces and applications must effectively translate UTC timestamps into a contextually relevant local time, taking into account daylight saving changes and regional variations, without introducing errors or confusion. Tools and libraries that handle these conversions reliably are an integral part of modern software development, ensuring that while the machines speak UTC, the users understand their local “what time is it?”

In conclusion, “What is the GMT time?” is far more than a simple question about a time zone. It delves into the very fabric of our technological world. From its humble origins at the Greenwich Observatory to its modern manifestation as UTC, this universal time standard is an invisible yet indispensable force. It enables the global coordination of autonomous systems, safeguards the integrity of digital data, fuels the intelligence of AI, and facilitates human collaboration on an unprecedented scale. As we push the boundaries of innovation, the precise and unambiguous rhythm of UTC will continue to be the heartbeat of technological progress.