To the casual observer, a drone is a feat of mechanical engineering—a symphony of carbon fiber, high-speed brushless motors, and lithium-polymer batteries. However, to a flight systems engineer, a drone is a floating laboratory of trigonometry. At the heart of every stable hover, every precision maneuver, and every autonomous waypoint mission lie two fundamental mathematical functions: sine and cosine.

While most of us remember these terms from high school geometry, in the world of flight technology, they are far more than abstract triangles on a chalkboard. They are the essential tools used by flight controllers to translate digital commands into physical motion. Understanding sine and cosine is critical to understanding how a modern Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) maintains its orientation, navigates the globe, and resists the unpredictable forces of nature.

The Fundamentals: How Trigonometry Translates Motion into Data

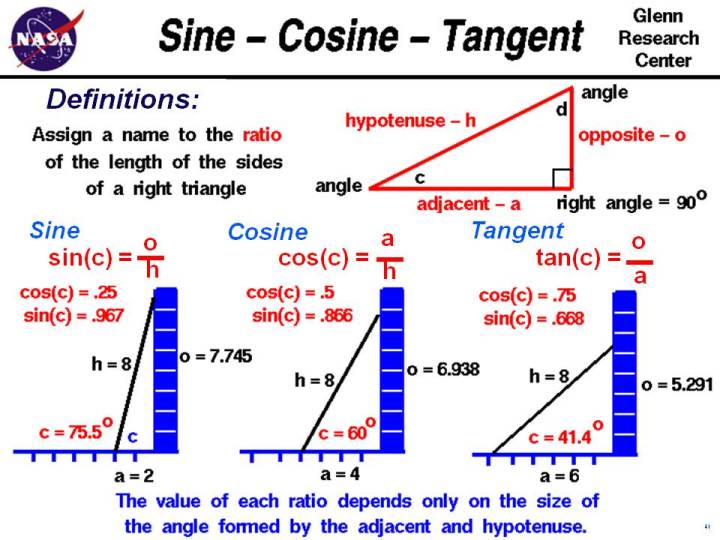

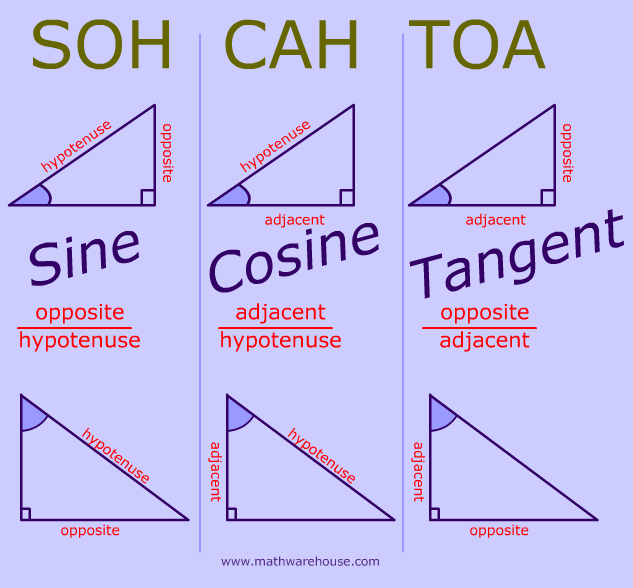

At its simplest level, trigonometry is the study of the relationships between the sides and angles of triangles. In flight technology, we use these relationships to break down complex movements into manageable components. When a drone moves through three-dimensional space, it doesn’t just move “forward” or “up”; it moves along a vector that has a specific magnitude and direction.

Defining Sine and Cosine in 3D Space

In the context of a flight controller, think of the drone’s movement as the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle. If a drone tilts forward at a specific angle to accelerate, the flight controller needs to know how much of its total motor thrust is pushing it forward (the horizontal component) and how much is keeping it in the air (the vertical component).

The cosine of the tilt angle determines the vertical lift, while the sine of that same angle determines the horizontal acceleration. Without these functions, the drone’s “brain” would be unable to calculate how much power to send to each motor to prevent the craft from losing altitude while trying to gain speed.

The Unit Circle and Propeller Rotation

Beyond movement, sine and cosine are rotational functions. A drone’s flight controller processes data in cycles, often at rates of 4kHz or 8kHz (thousands of times per second). The “Unit Circle”—a circle with a radius of one—is the mathematical model used to describe these oscillations. As the propellers spin and the internal sensors vibrate, sine and cosine waves help the flight controller filter out high-frequency noise from the actual movement data, ensuring that the stabilization system isn’t reacting to the mere vibration of the motors.

Flight Stabilization: Maintaining Level Flight via IMUs

The most impressive aspect of modern flight technology is “Locked-In” stability—the ability of a drone to remain perfectly level even in turbulent air. This is achieved through the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), which houses gyroscopes and accelerometers. These sensors are constantly outputting raw data that would be meaningless without trigonometric interpretation.

Euler Angles and the Roll, Pitch, Yaw Dynamics

Drones operate on three axes: Roll (tilting left or right), Pitch (tilting forward or back), and Yaw (rotating on the vertical axis). These are known as Euler angles. To maintain a steady hover, the flight controller must constantly solve for “Theta” (the angle of tilt).

If a gust of wind tips the drone 10 degrees to the left (Roll), the IMU detects this change. The onboard software immediately uses the sine of that 10-degree angle to calculate the “gravity vector” offset. By understanding exactly how much the drone has deviated from the horizontal plane, the flight controller can increase the RPM of the left-side motors to produce a counter-balancing force.

Accelerometers and Gyroscopes: Interpreting Vector Components

Accelerometers measure the force of gravity. When a drone is level, the gravity vector points straight down the Z-axis. However, when the drone maneuvers, gravity is distributed across the X, Y, and Z axes of the internal sensor.

To find the true orientation, the drone uses “Sensor Fusion.” It calculates the cosine of the angle between the drone’s body and the earth’s gravitational pull. If the cosine of the angle on the X-axis is anything other than zero, the drone knows it is not level. This constant trigonometric checking is what allows a drone to “know” which way is up, even when it is moving at high speeds or performing aggressive flips.

Navigation and Pathfinding: From 2D Coordinates to 3D Waypoints

While stabilization keeps the drone in the air, navigation tells it where to go. GPS technology provides us with latitude and longitude, but translating those coordinates into a flight path requires advanced spherical trigonometry.

The Haversine Formula and Global Positioning

Because the Earth is a sphere (or more accurately, an oblate spheroid), the distance between two GPS coordinates is not a straight line. To calculate the distance between a drone and its “Home” point, flight controllers use the Haversine Formula.

This formula relies heavily on both sine and cosine to calculate the “great-circle distance” between two points on a sphere. When you tap a location on your controller’s map, the drone isn’t just “driving” there; it is constantly calculating the sine of the latitudes and the cosine of the longitudes to ensure it is taking the most efficient path across the Earth’s curved surface.

Real-time Trajectory Correction

When a drone follows a pre-programmed flight path (Autonomous Waypoints), it rarely moves in a perfectly straight line due to environmental variables. If a drone needs to travel North-East at a 45-degree angle, the flight controller treats this as a vector.

- Cosine(45°) tells the drone how much power to apply to its lateral movement.

- Sine(45°) tells the drone how much power to apply to its longitudinal movement.

By balancing these two outputs, the drone maintains a precise diagonal trajectory. If the drone drifts off-course, the trigonometry is updated in real-time to create a new “correction vector” to bring it back to the line.

Wind Compensation and External Force Mitigation

One of the greatest challenges in flight technology is the “invisible hand” of the wind. A drone that appears to be hovering perfectly still in a 15-knot breeze is actually working incredibly hard. It is tilted into the wind, fighting to stay in one spot.

Vector Addition in Headwinds and Crosswinds

To maintain a stationary GPS hover in the wind, a drone must produce an equal and opposite force to the wind’s pressure. This is a classic problem of vector addition. If the wind is hitting the drone from the North-West at 30 degrees, the flight controller uses sine and cosine to break that wind force into its North and West components.

The drone then tilts its body at an angle where its horizontal thrust perfectly matches those components. The pilot sees a drone sitting still; the flight controller sees a complex trigonometric equation being solved 400 times per second to maintain that equilibrium.

The PID Loop and Trigonometric Feedback

The Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) loop is the software algorithm that governs how a drone reacts to change. When the drone’s sensors detect an error (e.g., the drone is 5 degrees off its target angle), the PID loop uses trigonometric functions to scale the response.

The “Proportional” aspect of the loop might say: “The error is the sine of 5 degrees; therefore, increase motor output by X amount.” This ensures that the correction is smooth. Without the scaling provided by sine and cosine, the drone’s movements would be jerky and unstable, as the motors would only have two states: “on” or “off,” rather than the nuanced, variable speeds required for fluid flight.

The Future of Trigonometry in Autonomous Flight

As we move toward a future of fully autonomous UAVs, the role of sine and cosine is expanding into the realm of computer vision and Obstacle Avoidance Systems. Technologies like LiDAR and Binocular Vision sensors work by projecting light or comparing two images to determine depth.

When a LiDAR sensor bounces a laser off a tree, it measures the time it took for the light to return. But to know where that tree is in 3D space, it must also know the exact angle of the sensor at the nanosecond the laser was fired. By taking the cosine of the sensor’s angle and multiplying it by the distance measured, the drone maps the obstacle into a 3D grid.

In conclusion, sine and cosine are not just relics of mathematics textbooks; they are the very language of flight. They allow a drone to interpret its environment, understand its own physical orientation, and navigate the world with a level of precision that was once reserved for military-grade aircraft. Every time you take to the skies, you are witnessing the incredible power of trigonometry in motion—translating the abstract beauty of mathematics into the breathtaking reality of flight technology.