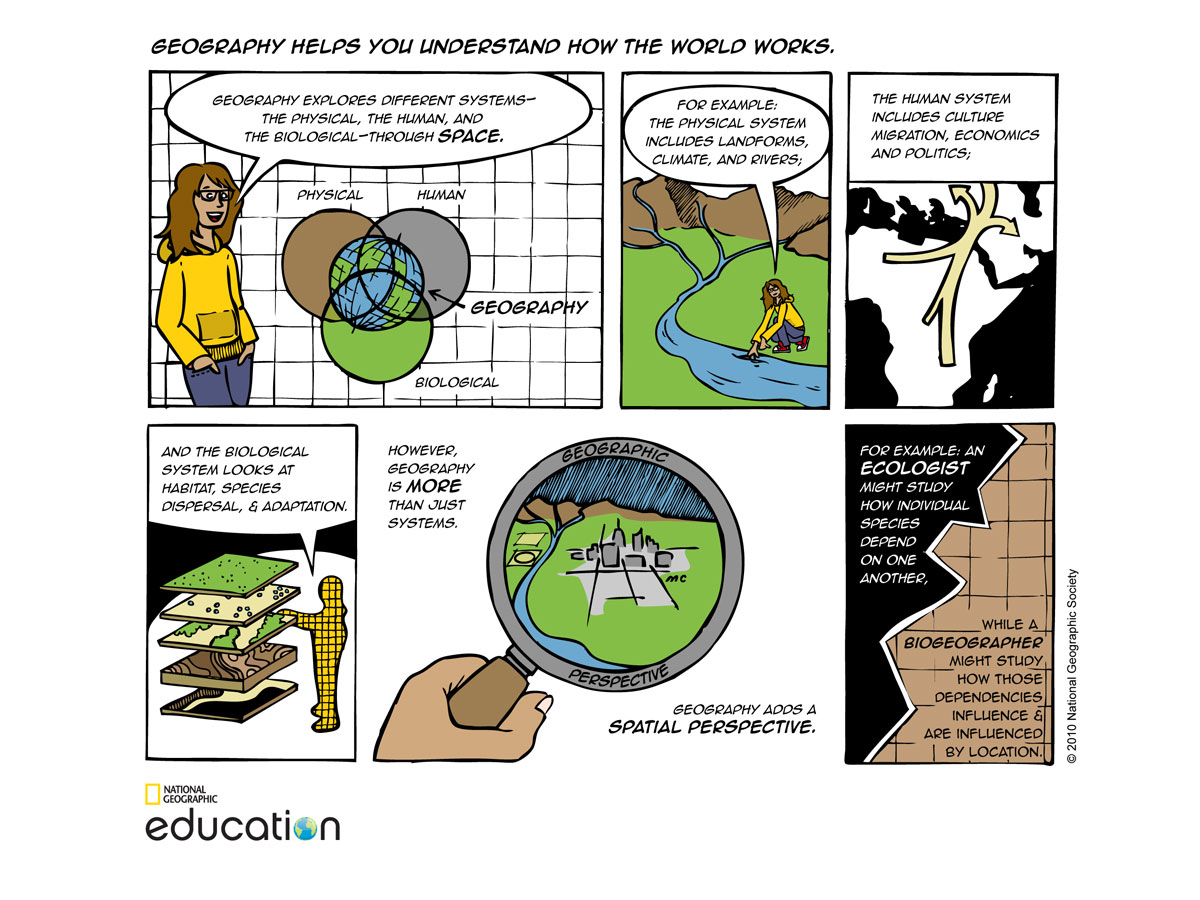

The term “geographic” directly relates to geography, the study of the Earth’s surface, its physical features, climate, population, and how these elements interact. In the context of technology, especially aerial technology, “geographic” often refers to the ability to understand, interact with, and map the physical space around a device. This involves a confluence of technologies that allow machines to perceive their location, their surroundings, and to process this information in a meaningful way. It’s about enabling a device, such as a drone, to have a spatial awareness, to navigate intelligently, and to perform tasks that are informed by its position and the characteristics of the environment it occupies.

The Foundation: Understanding Location and Position

At its core, understanding “geographic” in a technological context begins with accurately determining a device’s position in the world. This is the bedrock upon which all other geographic capabilities are built. Without a reliable sense of where it is, a device cannot truly engage with its surroundings in a geographically informed manner.

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS)

The most ubiquitous technology for establishing global position is the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). While often referred to by its most well-known component, GPS (Global Positioning System), GNSS encompasses a constellation of satellite networks operated by various countries. These systems work by receiving signals from multiple satellites orbiting the Earth. By measuring the time it takes for these signals to reach the receiver, and knowing the precise location of the satellites, a device can triangulate its own position with remarkable accuracy.

- GPS (United States): The original and most widely recognized GNSS, providing foundational positioning data.

- GLONASS (Russia): A comparable system to GPS, offering an alternative and often complementary satellite network.

- Galileo (European Union): A highly precise and modern GNSS, designed for both civilian and professional use, offering advanced features like increased accuracy and integrity monitoring.

- BeiDou (China): A rapidly expanding GNSS that provides global coverage and is integral to China’s technological infrastructure.

The integration of multiple GNSS signals allows devices to achieve greater accuracy and reliability, especially in challenging environments where signals from a single system might be weak or obstructed. This multi-constellation capability is crucial for applications demanding high precision, such as surveying, precision agriculture, and autonomous navigation.

Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs)

While GNSS provides absolute positioning, Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) offer a way to track relative motion and orientation. An IMU is a sophisticated sensor package that typically includes accelerometers and gyroscopes. Accelerometers measure linear acceleration, while gyroscopes measure angular velocity. By integrating these measurements over time, an IMU can estimate changes in position, velocity, and orientation.

- Accelerometers: Detect linear forces, allowing the device to sense movement along its axes.

- Gyroscopes: Measure rotational movement, enabling the device to track its pitch, roll, and yaw.

- Magnetometers: Sometimes included in IMUs, these sensors measure the Earth’s magnetic field, providing a compass-like orientation reference.

IMUs are vital for maintaining stability and tracking movement between GNSS updates. They are particularly important during periods of signal loss, such as when a drone flies indoors or through dense foliage. By fusing data from GNSS and IMUs, a device can achieve a more continuous and accurate estimate of its state, a process known as sensor fusion.

Dead Reckoning and Visual Odometry

Beyond satellite-based and inertial navigation, other techniques contribute to a device’s geographic understanding, especially in environments where GNSS is unavailable or unreliable. Dead reckoning uses a known starting point and estimates current position by calculating successive movements. Visual odometry, on the other hand, uses cameras to track the movement of features in the environment. By analyzing the changes in these features between successive camera frames, the device can estimate its own motion.

- Dead Reckoning: A continuous estimation of position, often used in conjunction with other navigation systems to bridge gaps or improve accuracy.

- Visual Odometry: Leverages camera input to perceive motion relative to the environment, a key component in many autonomous systems.

These methods are particularly relevant for indoor navigation or for drones operating in complex urban canyons where GNSS signals can be heavily degraded or entirely blocked.

Sensing the Environment: Beyond Position

Understanding “geographic” is not solely about knowing where a device is; it’s also about comprehending the features and characteristics of its surrounding environment. This involves a suite of sensors that perceive the world in various ways, providing data that informs navigation, mapping, and interaction.

Environmental Perception Sensors

These sensors are designed to detect and interpret the physical world around the device. They provide the raw data that allows a device to “see” and “understand” its geographic context.

- Cameras (Visible Spectrum): Standard cameras capture visual information, allowing for object recognition, scene understanding, and visual mapping. The quality and type of camera (e.g., resolution, frame rate, lens) significantly impact the detail and clarity of the geographic information captured.

- Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging): Lidar systems emit laser pulses and measure the time it takes for them to reflect off objects. This creates a detailed 3D point cloud of the environment, providing precise measurements of distances and shapes. Lidar is instrumental in creating highly accurate 3D maps and for obstacle detection.

- Radar (Radio Detection and Ranging): Radar uses radio waves to detect objects and their distance, velocity, and direction. It is less affected by weather conditions like fog or rain compared to Lidar or optical cameras, making it valuable for all-weather sensing.

- Ultrasonic Sensors: These sensors emit sound waves and measure the time for the echo to return, providing short-range distance measurements. They are commonly used for close-proximity obstacle avoidance and precise landing.

Obstacle Avoidance Systems

A critical aspect of geographic awareness is the ability to safely navigate around obstacles. This relies heavily on a combination of sensors and sophisticated algorithms.

- Forward and Downward Facing Sensors: Many systems use cameras and/or ultrasonic sensors to detect obstacles directly in front of or below the device.

- 360-Degree Sensing: Advanced systems incorporate multiple sensors to provide a comprehensive view of the surrounding environment, detecting obstacles in all directions.

- Predictive Algorithms: These algorithms not only detect current obstacles but also predict potential collisions based on the device’s trajectory and the movement of surrounding objects.

The effective integration of these sensors allows a device to build a dynamic, real-time understanding of its geographic space, enabling it to fly, move, and operate without colliding with its surroundings.

Geographic Data Processing and Application

The raw data gathered by sensors is only useful when it is processed, interpreted, and applied to specific tasks. This involves transforming sensor readings into actionable geographic information.

Mapping and Surveying

One of the most significant applications of geographic awareness in technology is in the creation of maps and the performance of surveys.

- Orthomosaics: By stitching together multiple aerial images taken from different angles and locations, a highly accurate and georeferenced 2D map, known as an orthomosaic, can be created. These maps are geometrically corrected and can be used for precise measurements and analysis.

- 3D Models: Using data from Lidar, photogrammetry (the process of creating 3D models from images), or a combination of both, detailed 3D models of landscapes, buildings, and infrastructure can be generated. These models are invaluable for planning, inspection, and visualization.

- Topographic Mapping: Creating maps that represent the elevation and shape of the land surface is a classic geographic application, now greatly enhanced by aerial technology.

Georeferencing and Spatial Analysis

Georeferencing is the process of assigning real-world coordinates to data. This allows geographic data to be precisely located on a map and integrated with other spatial datasets.

- Coordinate Systems: Understanding and utilizing different coordinate systems (e.g., Latitude/Longitude, UTM) is fundamental to georeferencing.

- Spatial Analysis: Once data is georeferenced, it can be subjected to spatial analysis. This involves examining the relationships between geographic features and their distribution. Examples include calculating distances, identifying patterns, and performing suitability analysis.

Autonomous Navigation and Path Planning

The ultimate expression of geographic awareness is the ability for a device to navigate autonomously. This requires sophisticated algorithms that can process geographic information to plan and execute flight paths.

- Waypoint Navigation: Pre-programmed flight paths defined by a series of geographic coordinates (waypoints) that the device follows.

- Dynamic Path Planning: The ability to adjust the flight path in real-time based on sensor data, environmental changes, and mission objectives. This includes avoiding obstacles, following specific features, or maintaining optimal survey patterns.

- Geofencing: Establishing virtual boundaries in geographic space to restrict a device’s movement within or outside of defined areas. This is crucial for safety and regulatory compliance.

In essence, “geographic” in the realm of technology signifies a device’s ability to understand its place in the world, perceive its surroundings with precision, and leverage this spatial intelligence to perform complex tasks, from simple navigation to advanced data acquisition and analysis. It’s the bridging of the physical world with the digital realm, enabling machines to interact with and understand the Earth in ways previously unimaginable.