The Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test has long been a subject of fascination and debate. While widely used as a measure of cognitive ability, the precise nature of what it quantifies remains a complex and multifaceted question. Far from being a simple assessment of innate brilliance, an IQ test endeavors to gauge a range of mental aptitudes that contribute to an individual’s ability to learn, reason, solve problems, and adapt to new situations. Understanding what these tests truly measure requires a deeper dive into their historical development, the specific cognitive domains they assess, and the ongoing scientific discussion surrounding their validity and interpretation.

The Multifaceted Nature of Intelligence

The concept of intelligence itself is not a monolithic entity but rather a spectrum of cognitive capabilities. Historically, early attempts to measure intelligence were driven by practical needs, such as identifying children who required specialized educational support. Over time, these assessments evolved, moving from simple observational methods to more standardized and psychometrically rigorous tests. The prevailing understanding today is that intelligence encompasses multiple facets, each contributing to an individual’s overall cognitive profile.

Early Theories and Evolution of IQ Testing

The origins of IQ testing can be traced back to the early 20th century, with pioneers like Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon developing the first practical intelligence test in France. Their goal was to identify children who would benefit from additional educational resources, focusing on abilities such as attention, memory, and problem-solving. The concept of a “mental age” was introduced, comparing a child’s performance to the average performance of children of a specific chronological age.

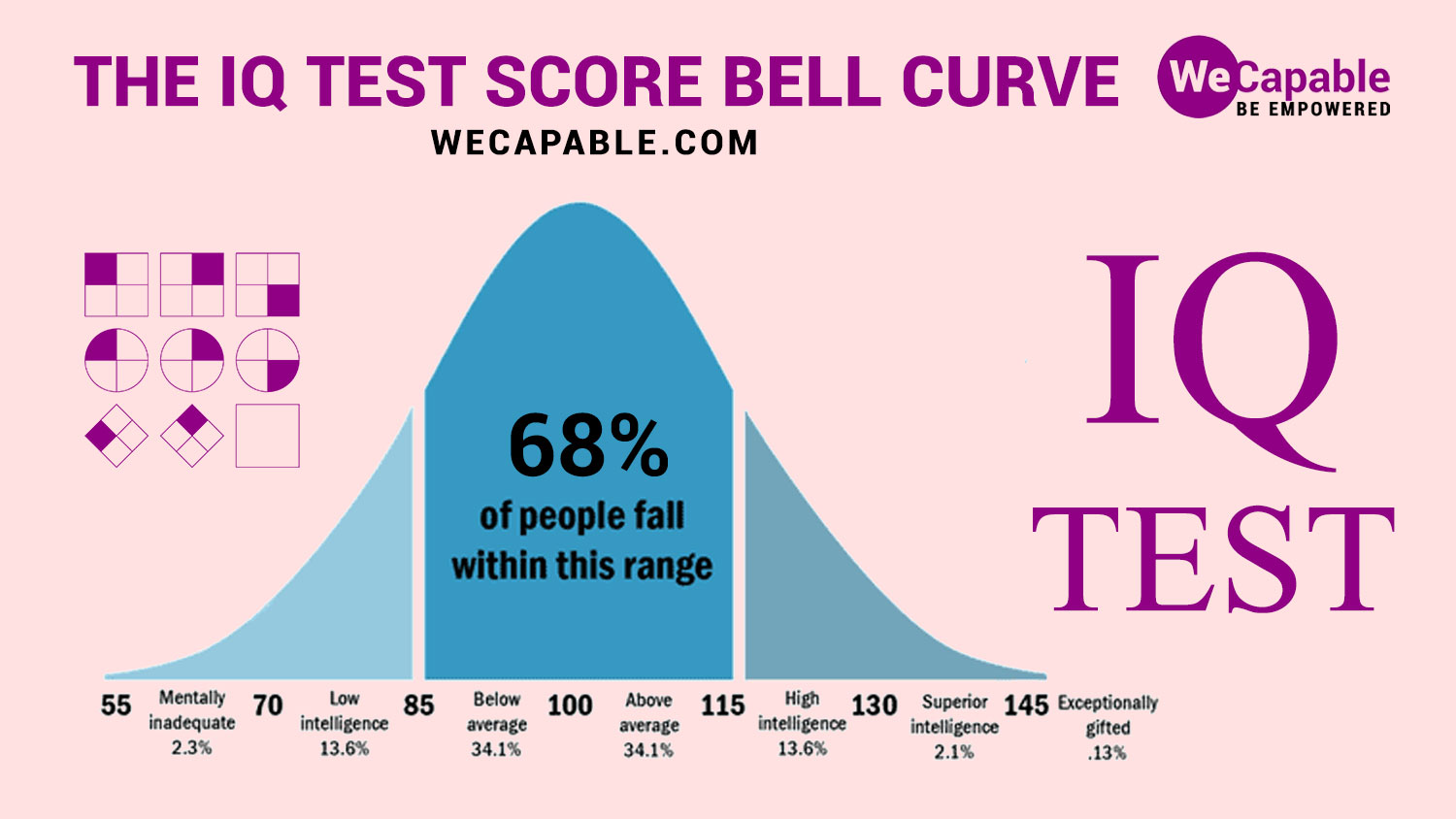

This early work was later refined and popularized by Lewis Terman at Stanford University, who developed the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales. Terman introduced the ratio of mental age to chronological age, multiplied by 100, to derive the Intelligence Quotient (IQ). While groundbreaking, this ratio approach proved problematic for adults, as mental age doesn’t linearly increase indefinitely. The modern definition of IQ, as used in most contemporary tests, relies on a deviation score, comparing an individual’s performance to the average performance of their age group, typically with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

Beyond a Single Score: Multiple Intelligences

As psychological research progressed, it became increasingly clear that a single IQ score might not fully capture the breadth of human cognitive abilities. Howard Gardner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences, for instance, proposed that individuals possess several distinct types of intelligence, including linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. While these intelligences are not directly measured by traditional IQ tests, Gardner’s work highlights the limitations of a narrow definition of intelligence.

Similarly, Robert Sternberg’s Triarchic Theory of Intelligence suggests three fundamental aspects: analytical, creative, and practical intelligence. Analytical intelligence, often most emphasized in traditional IQ tests, involves problem-solving and abstract reasoning. Creative intelligence relates to the ability to generate novel ideas and solutions. Practical intelligence, often termed “street smarts,” pertains to the ability to adapt to and function effectively in everyday environments. While some modern IQ tests attempt to incorporate elements of these broader intelligences, the core of what is measured often remains rooted in analytical and logical reasoning.

Cognitive Domains Assessed by IQ Tests

Contemporary IQ tests, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) and the Stanford-Binet, are designed to assess a range of cognitive abilities that are considered fundamental to intellectual functioning. These tests typically break down performance into several key domains, each tapping into different aspects of cognitive processing.

Verbal Comprehension

The Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) measures an individual’s ability to understand and use spoken language, as well as their acquired knowledge and reasoning with verbal concepts. This sub-section often includes tasks like:

- Vocabulary: Defining words and understanding their nuances. This assesses a person’s learned knowledge of language and their ability to access and articulate word meanings.

- Similarities: Identifying the common relationship between two words. This tests abstract verbal reasoning and the ability to categorize and generalize. For example, asking “In what way are an apple and a banana alike?” requires the respondent to go beyond superficial similarities to conceptual ones, like “both are fruits.”

- Information: Answering general knowledge questions. This reflects an individual’s accumulated knowledge about the world, often acquired through formal education and life experiences. It assesses the breadth and depth of learned information.

- Comprehension (sometimes): Explaining the meaning of proverbs or providing common-sense answers to social situations. This measures practical judgment and the ability to understand social conventions and abstract concepts related to human interaction.

The VCI is crucial because language is a primary tool for thought and communication. A strong performance in this domain suggests an individual can effectively process and utilize verbal information, a cornerstone of academic learning and complex cognitive tasks.

Perceptual Reasoning

The Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI) evaluates an individual’s non-verbal reasoning abilities, visual-spatial processing, and the ability to organize visual information. This domain is particularly important for understanding how individuals process and make sense of the world around them through visual and tactile input. Key sub-tests include:

- Block Design: Recreating a given pattern using colored blocks. This assesses visual-spatial reasoning, pattern recognition, and the ability to analyze and synthesize visual information. It requires manipulating abstract representations in one’s mind.

- Matrix Reasoning: Completing a visual pattern or sequence. This involves identifying abstract relationships and logical patterns within visual stimuli, often requiring inductive and deductive reasoning. This is akin to solving visual analogies.

- Visual Puzzles: Assembling a whole image from its constituent parts. This tests the ability to decompose and recompose visual information, understanding part-whole relationships and spatial arrangement.

- Figure Weights (sometimes): Identifying a missing element in a visually presented balance scale or matrix based on proportional reasoning. This assesses quantitative and logical reasoning applied to visual representations.

Perceptual reasoning is vital for tasks requiring spatial awareness, mechanical aptitude, and the ability to understand diagrams, maps, and visual data. It reflects how well individuals can think and problem-solve visually.

Working Memory

The Working Memory Index (WMI) measures an individual’s ability to hold and manipulate information in their mind for a short period. This is a critical component for complex cognitive tasks, learning, and reasoning. Working memory is the mental workspace where information is temporarily stored and processed. Components typically include:

- Digit Span: Repeating a sequence of numbers presented auditorily, forwards and backward. The forward portion assesses attention and immediate recall, while the backward portion requires manipulation and mental reversal of the information, indicating active processing.

- Arithmetic: Solving mathematical problems mentally. This tests numerical reasoning, the ability to recall mathematical rules, and the capacity to hold and manipulate numbers in working memory to arrive at a solution.

- Letter-Number Sequencing: Repeating a mixed sequence of letters and numbers in a specific order (numbers first, then letters). This requires holding distinct types of information and reorganizing them according to a rule, demonstrating both memory capacity and executive control.

A robust working memory is essential for tasks requiring sustained attention, logical reasoning, and the ability to follow complex instructions or engage in multi-step problem-solving. Deficits in working memory can significantly impact learning and daily functioning.

Processing Speed

The Processing Speed Index (PSI) assesses how quickly and accurately an individual can perform simple cognitive tasks. This domain is about the efficiency of cognitive operations. It reflects the speed at which information can be processed and acted upon. Common sub-tests involve:

- Symbol Search: Identifying whether a target symbol appears in a list of symbols within a time limit. This requires visual scanning, discrimination, and rapid decision-making.

- Coding (or Digit Symbol Substitution): Matching symbols to numbers or vice versa according to a key, as quickly as possible. This involves learning a simple code and applying it with speed and accuracy, demonstrating psychomotor speed and visual-motor coordination.

Processing speed is often considered a marker of overall cognitive efficiency. While not directly measuring the complexity of thought, it influences how quickly an individual can complete tasks that require cognitive effort, impacting performance in other areas and in real-world situations.

Interpretation and Limitations of IQ Tests

While IQ tests provide valuable insights into certain cognitive abilities, it is crucial to understand their interpretation and acknowledge their inherent limitations. The score itself is not a definitive measure of a person’s worth, intelligence, or potential.

Statistical Significance and Predictive Validity

IQ tests are designed to be statistically reliable and valid measures of the cognitive abilities they purport to assess. This means that the scores are consistent over time (reliability) and that they measure what they are intended to measure (validity). Research has consistently shown that IQ scores have predictive validity for academic achievement and, to a lesser extent, occupational success. Individuals with higher IQ scores tend to perform better in school and are more likely to attain higher levels of education and professional positions.

However, it’s important to note that “predictive validity” does not mean perfect prediction. Many other factors, such as motivation, personality, social skills, opportunities, and environmental influences, play significant roles in an individual’s life outcomes. An IQ score is just one piece of a much larger puzzle.

Cultural Bias and Environmental Factors

A significant area of debate surrounding IQ tests concerns potential cultural bias. Historically, some tests have been criticized for relying on knowledge and language more familiar to individuals from specific cultural backgrounds, potentially disadvantaging those from different environments. While test developers strive to minimize cultural loading, complete neutrality is difficult to achieve.

Furthermore, environmental factors play a profound role in cognitive development. A child’s upbringing, access to quality education, nutrition, and stimulation all significantly influence their cognitive abilities. Therefore, an IQ score reflects a combination of genetic predispositions and environmental influences up to the point of testing. It is not a static, unchangeable measure of innate potential.

The Dynamic Nature of Intelligence

Intelligence is not a fixed entity but can evolve and develop over time. While IQ scores tend to be relatively stable in adulthood, significant life experiences, learning opportunities, and targeted interventions can influence cognitive functioning. Furthermore, different life demands may emphasize different cognitive skills. For example, a person might have a moderate IQ score but excel in a field that requires immense creativity or interpersonal skill, areas not fully captured by traditional IQ measures.

In conclusion, IQ tests measure a specific set of cognitive abilities, primarily focusing on logical reasoning, verbal comprehension, perceptual skills, working memory, and processing speed. They are valuable tools for understanding an individual’s cognitive profile in these areas and have demonstrated predictive validity for academic and occupational success. However, they are not exhaustive measures of all forms of intelligence and should be interpreted within the broader context of an individual’s life, environment, and other multifaceted talents and abilities. The ongoing research and discussion surrounding intelligence continue to refine our understanding of what it truly means to be cognitively capable.