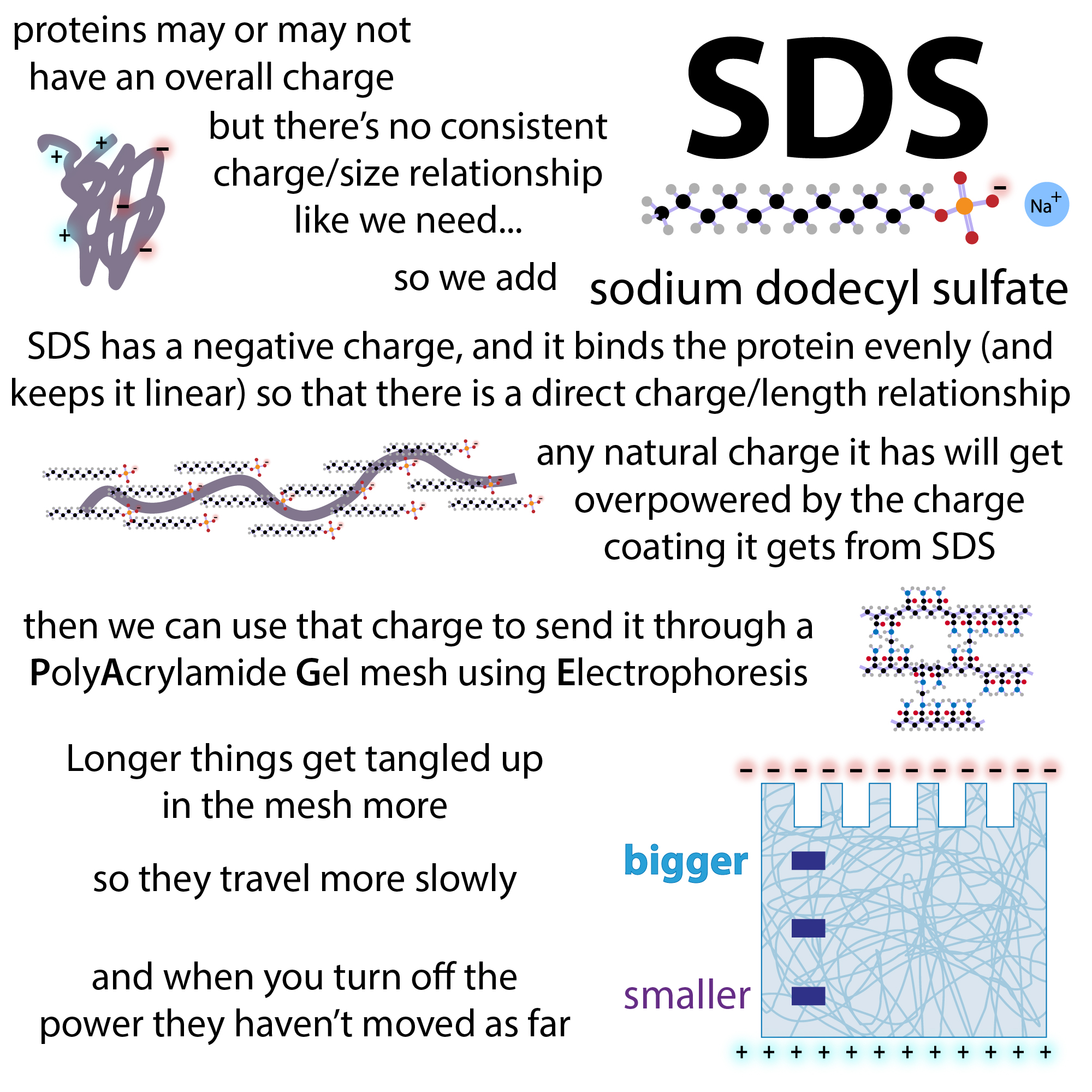

The acronym SDS-PAGE stands for Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis. While the “PAGE” component clearly points to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, a fundamental technique in molecular biology for separating proteins based on size, the role of “SDS” is often less immediately apparent to those new to the field. Sodium dodecyl sulfate, commonly abbreviated as SDS, is not merely a passive additive in this process; it is an indispensable detergent that fundamentally dictates the effectiveness and interpretability of the SDS-PAGE technique. Its actions are crucial for ensuring that the separation achieved is primarily based on molecular weight, a cornerstone of protein analysis.

The Denaturing Power of SDS: Unleashing the Polypeptide Chain

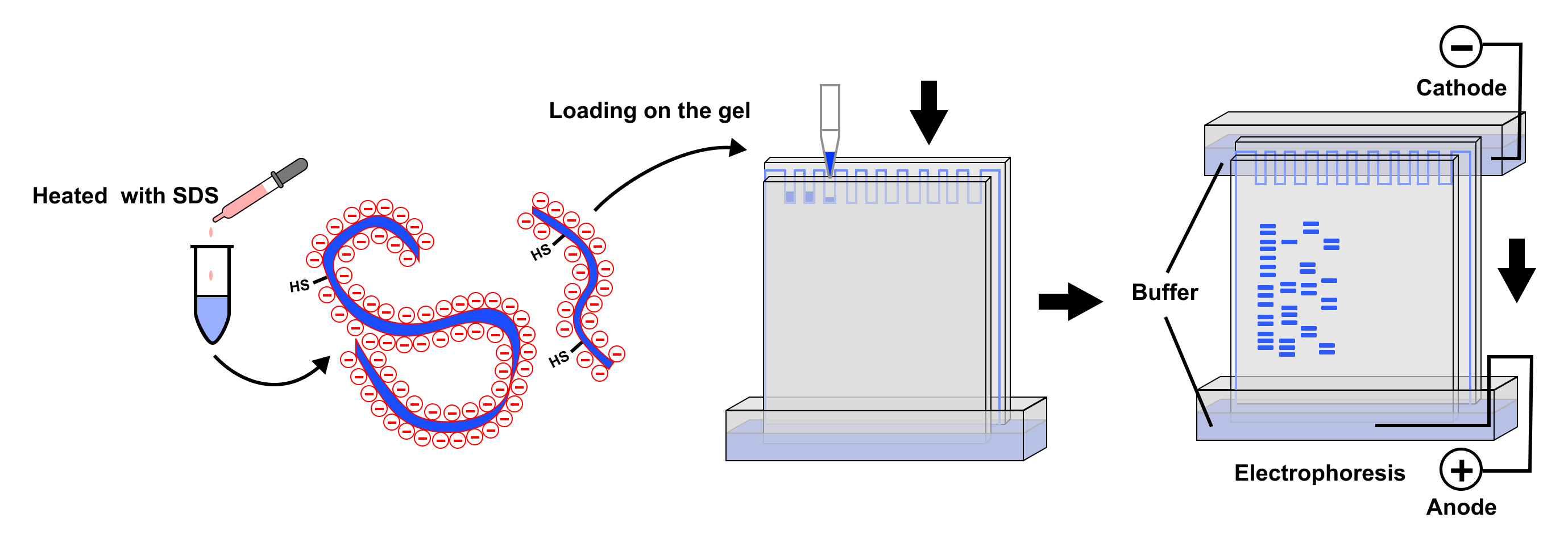

SDS exerts its primary influence by acting as a potent denaturant. Proteins, in their native state, fold into complex three-dimensional structures dictated by a multitude of interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, ionic bonds, and disulfide bridges. These intricate folds are essential for a protein’s function but pose a significant obstacle to size-based separation. If proteins were to migrate through the gel in their native conformations, their migration speed would be a complex function of their size, shape, and charge, making accurate molecular weight determination virtually impossible.

Disrupting Non-Covalent Interactions: Unfolding the Protein’s Architecture

The key to SDS’s denaturing power lies in its amphipathic nature. SDS is an anionic surfactant, meaning it possesses a hydrophobic tail (the dodecyl chain) and a hydrophilic head (the sulfate group). In aqueous solutions, SDS molecules form micelles. When added to protein samples, these SDS micelles readily bind to hydrophobic regions of the protein. This binding initiates a cascade of unfolding. The hydrophobic tails of SDS molecules intercalate into the protein’s interior, disrupting the hydrophobic core that stabilizes the folded structure. Simultaneously, the hydrophilic sulfate heads interact with water, further driving the unfolding process.

This disruption extends to the various non-covalent interactions that maintain protein tertiary and quaternary structure. Hydrogen bonds are weakened and broken as SDS molecules insert themselves between amino acid residues. Ionic interactions, formed between oppositely charged amino acid side chains, are shielded by the charged sulfate heads of SDS, diminishing their attractive forces. The overall effect is the systematic dismantling of the protein’s complex three-dimensional architecture, reducing it to a linear, unfolded polypeptide chain.

Disrupting Disulfide Bonds: Liberating Subunits

While SDS primarily targets non-covalent interactions, its presence, often in conjunction with reducing agents like beta-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), also plays a role in breaking covalent disulfide bonds. These disulfide bridges, formed between cysteine residues, are crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of many proteins, particularly in their native state. When proteins are heated in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent, the disulfide bonds are cleaved, yielding free sulfhydryl groups. This further ensures that the protein is fully linearized and that any subunit interactions held together by disulfide bonds are broken, allowing for the separation of individual polypeptide chains. The complete unfolding and reduction of proteins into their constituent polypeptide chains are critical prerequisites for size-based separation in SDS-PAGE.

Imparting a Uniform Negative Charge: The Charge-to-Mass Ratio Predominance

Beyond its denaturing capabilities, SDS plays another critical role: it imparts a strong, uniform negative charge to the unfolded polypeptide chains. The sulfate head group of SDS carries a net negative charge. In an SDS-PAGE sample buffer, SDS is present in a large molar excess relative to the protein. This excess ensures that SDS molecules bind to the protein backbone in a relatively constant ratio. For every two amino acid residues in the polypeptide chain, approximately one SDS molecule binds. This extensive binding saturates the protein with negative charges.

Overcoming Intrinsic Protein Charge: The Dominance of SDS

Native proteins possess a net charge that varies depending on their amino acid composition and the pH of the surrounding environment. This intrinsic charge significantly influences their electrophoretic mobility. If this intrinsic charge were to remain dominant, the separation in electrophoresis would be a complex interplay of size, shape, and charge, rendering accurate molecular weight estimations challenging.

However, the sheer number of SDS molecules that bind to the unfolded polypeptide chain effectively masks the protein’s intrinsic charge. The negative charge contributed by the SDS molecules far outweighs the protein’s inherent charge. This phenomenon ensures that virtually all proteins, regardless of their initial amino acid composition, acquire a comparable and predominantly negative charge-to-mass ratio. This uniformity is the linchpin of SDS-PAGE’s ability to separate proteins based on size.

Establishing a Consistent Charge-to-Mass Ratio: The Foundation of Size-Based Separation

By conferring a uniform negative charge, SDS ensures that the primary driving force during electrophoresis is the interaction between the negatively charged protein-SDS complexes and the positively charged electrode. The electric field exerts a force on these complexes, pulling them towards the anode. The rate at which they migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix is then primarily determined by their size and shape. Since the proteins are unfolded and uniformly coated with SDS, their shapes are largely similar, resembling linear rods. Therefore, larger polypeptides encounter more resistance from the gel matrix and migrate slower, while smaller polypeptides navigate the pores more easily and migrate faster. This consistent charge-to-mass ratio, established by SDS, is the fundamental principle that allows SDS-PAGE to function as a powerful tool for estimating protein molecular weights.

Facilitating Migration and Interaction with the Gel Matrix: The Detergent’s Lubricating Effect

The presence of SDS also influences the interaction of the protein-SDS complexes with the polyacrylamide gel matrix. The gel itself is a cross-linked polymer network that forms pores of varying sizes. The separation of molecules is based on their ability to navigate these pores.

Reducing Frictional Forces: Smooth Passage Through the Gel

The hydrophobic tails of the SDS molecules, even after binding to the protein, can interact with the hydrophobic regions of the polyacrylamide gel matrix. This interaction, coupled with the overall hydrophilic nature of the SDS-coated protein, can be thought of as a form of “lubrication.” This effect reduces the frictional forces that would otherwise impede the movement of larger, more irregularly shaped molecules through the gel. While the gel matrix is the primary source of sieving and resistance, SDS helps to ensure that this resistance is predominantly a function of the polypeptide chain’s length, rather than its propensity to snag or get stuck due to unfavorable interactions with the gel material.

Uniform Interaction with the Gel: Predictable Sieving

By creating a relatively uniform, rod-like structure for all proteins and coating them with a charged, somewhat hydrophobic layer, SDS promotes a more predictable and uniform interaction with the gel matrix. The pores of the gel act as a sieve. Larger protein-SDS complexes will be sterically hindered by the gel pores, slowing their migration. Smaller complexes will pass through more readily. Without the consistent size and charge imparted by SDS, the interaction of proteins with the gel would be highly variable, influenced by specific binding affinities between the protein and the gel matrix, or by the protein’s native conformation stubbornly trying to squeeze through pores. SDS minimizes these confounding factors, making the sieving process more efficient and the results more interpretable in terms of molecular weight.

In essence, SDS transforms a heterogeneous collection of folded proteins with diverse charges and shapes into a collection of uniformly charged, linear molecules whose migration is primarily governed by their length as they navigate the porous gel. This simplification is the very reason SDS-PAGE has become a ubiquitous and indispensable technique in molecular biology.