In the rapidly evolving landscape of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and high-endurance flight technology, the focus often shifts toward battery density and electric motor efficiency. However, for the heavy-lift, long-endurance, and industrial sectors of the drone industry, internal combustion engines (ICE) and hybrid-electric powerplants remains the gold standard for sustained operations. In these sophisticated machines, the lifeblood of the propulsion system is its lubricant. Understanding what causes a loss of oil pressure is not merely a matter of mechanical curiosity; it is a critical component of flight safety, asset protection, and mission success.

As flight technology pushes into more extreme environments—ranging from high-altitude atmospheric research to long-range maritime surveillance—the stress placed on the oiling systems of gas-powered UAVs increases exponentially. A sudden drop in oil pressure can lead to catastrophic engine failure within seconds, resulting in the total loss of the aircraft. This article explores the intricate mechanics, environmental factors, and technological vulnerabilities that contribute to oil pressure loss in the context of modern flight technology.

The Role of Lubrication in High-Performance UAV Engines

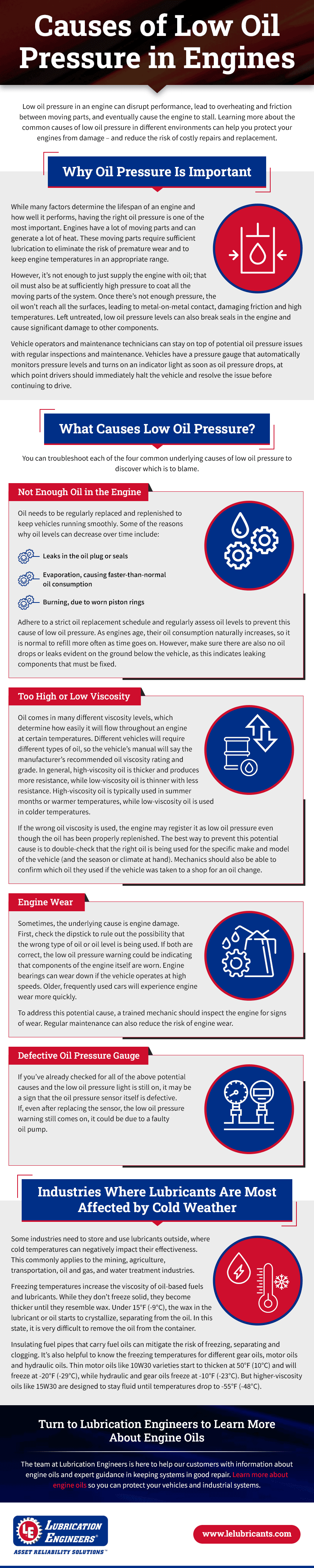

To understand failure, one must first understand the function. In flight technology, oil serves three primary purposes: lubrication, cooling, and debris management. Unlike terrestrial vehicles, UAVs often operate at high RPMs for hours on end, necessitating a flawless pressurized system to keep internal components separated by a microscopic film of oil.

Lubrication and Friction Reduction

At the heart of any combustion-based flight system are moving parts—pistons, crankshafts, and camshafts—that move at incredible velocities. The oil pressure system ensures that these metal surfaces never actually touch. If the pressure drops, the hydrodynamic wedge that supports these loads collapses. In the context of a drone operating several kilometers away from its pilot, this friction leads to “seizing,” where the heat generated by metal-on-metal contact welds parts together mid-flight.

Thermal Management in Sustained Flight

While liquid or air cooling handles the exterior of the engine block, oil is the primary cooling agent for the internal components. In high-performance UAVs, oil is circulated through a heat exchanger (oil cooler) before being pumped back into the engine. A loss of pressure means a loss of flow, which causes internal temperatures to spike. This thermal runaway can warp cylinder heads and degrade the structural integrity of the engine casing, leading to a complete “black-sky” failure event.

Primary Mechanical Causes of Oil Pressure Drops

Mechanical failure remains the most common culprit behind oil pressure issues. Because UAVs are designed with weight-saving measures in mind, components are often built to tight tolerances, leaving little room for error.

Pump Failure and Mechanical Wear

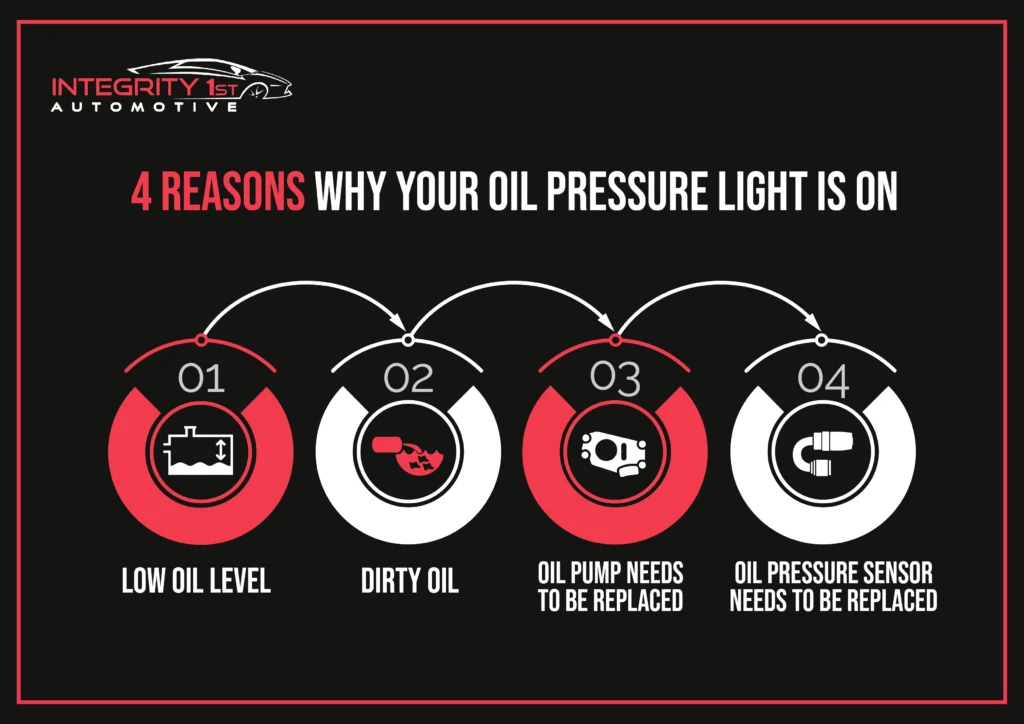

The oil pump is the heart of the flight technology’s propulsion system. Most UAV engines utilize a positive displacement pump geared directly to the crankshaft. If the drive gear shears or if the internal rotors of the pump sustain wear from microscopic particulates, the pump loses its ability to generate the necessary PSI (pounds per square inch). In professional flight operations, pump efficiency is monitored via telemetry; a gradual decline usually indicates wear, while a sudden drop indicates a mechanical shear.

Seal Breaches and External Leaks

Flight systems are subject to intense vibrations, especially in multi-rotor gas hybrids or fixed-wing UAVs with high-vibration powerplants. These vibrations can lead to the “backing out” of bolts or the degradation of gaskets and O-rings. An external leak is a dual threat: it depletes the total volume of oil available and creates a fire hazard if the oil contacts the hot exhaust manifold. In the realm of advanced flight technology, even a minor weep can become a major spray under the high-pressure conditions of cruising altitude.

Contamination and Filter Blockages

The oil filter’s job is to trap carbon deposits and metallic shavings. However, if an engine is pushed beyond its service interval, or if internal components begin to fail, the filter can become “blinded” or clogged. Most aviation engines include a bypass valve that allows unfiltered oil to circulate if the filter is blocked, but this is a temporary fix. If the blockage occurs at the oil pickup screen (the “strainer” in the sump), the pump will cavitate—sucking in air instead of fluid—resulting in an immediate and total loss of pressure.

Environmental and Operational Factors

Flight technology does not operate in a vacuum. The environment plays a massive role in how lubricants behave, and failing to account for these variables is a leading cause of pressure-related incidents.

Extreme Altitudes and Temperature Fluctuations

As a UAV climbs, the ambient temperature drops significantly. This affects the kinematic viscosity of the oil. If the oil becomes too thick (high viscosity) due to extreme cold, the pump may struggle to move it through the narrow galleries, leading to a “pressure spike” followed by a drop as the pump starves. Conversely, at high operating temperatures, the oil can become too thin, failing to provide the resistance necessary for the pump to build pressure. Modern flight technology often employs “multi-grade” synthetic oils designed to handle these swings, but even these have limits.

Aggressive Maneuvering and G-Force Impacts

In tactical or racing UAVs, high-G maneuvers are common. Standard “wet sump” engines, where oil sits in a pan at the bottom of the engine, are susceptible to “oil starvation” during steep dives, high-speed banks, or rapid climbs. Centrifugal force pushes the oil to the sides of the pan, away from the pickup tube. Advanced flight technology mitigates this through “dry sump” systems, which use multiple scavenge pumps and an external reservoir to ensure the engine is fed oil regardless of the aircraft’s orientation. A failure in any one of these scavenge lines will lead to an immediate pressure drop.

Monitoring and Mitigation via Sensor Technology

The “Tech” in flight technology is nowhere more apparent than in the sensor arrays used to monitor engine health. Modern UAVs are equipped with a suite of sensors that provide a digital window into the oily depths of the powerplant.

Real-Time Telemetry and Low-Pressure Alerts

Advanced flight controllers now integrate oil pressure transducers that send real-time data to the Ground Control Station (GCS). These sensors use piezo-resistive technology to convert physical pressure into an electrical signal. If the pressure falls below a pre-defined threshold—calibrated for the specific engine and altitude—the flight software can trigger an automated “Return to Home” (RTH) or an emergency landing sequence. This autonomous response is vital, as a human pilot might not notice a flickering gauge in time to save the aircraft.

Redundancy Systems and Emergency Protocols

In high-value flight operations, redundancy is key. Some high-end UAV propulsion systems utilize dual oil pumps or secondary pressure sensors to cross-validate data. If Sensor A reports 10 PSI and Sensor B reports 50 PSI, the flight logic recognizes a sensor failure rather than a mechanical failure, preventing an unnecessary emergency landing. Furthermore, the use of “Acoustic Emissions” sensors is an emerging field in flight tech, where AI-driven algorithms listen for the specific sound frequency of a starving oil pump before the pressure even drops.

Maintenance Protocols for Long-Endurance Flight Systems

The prevention of oil pressure loss is rooted in rigorous maintenance and the application of predictive analytics. In the professional drone industry, “fix it when it breaks” is replaced by “fix it before it fails.”

Pre-flight Inspection Rigor

Before any long-range flight, the “flight technology checklist” must include a verification of oil levels and a check for “milky” oil (indicating coolant contamination) or “glittery” oil (indicating bearing wear). Technicians also inspect the “oil breather” system, which regulates internal crankcase pressure. A clogged breather can cause internal pressure to build up to the point where it blows out a main seal, leading to an immediate loss of oil and pressure.

Predictive Analytics in Flight Technology

The future of UAV maintenance lies in “Condition-Based Monitoring.” By analyzing the historical data of oil pressure versus engine temperature and RPM, flight teams can predict when a pump is nearing the end of its life cycle. Spectrographic oil analysis is another tool borrowed from general aviation, where a small sample of oil is burned in a lab to see which metals are present. If high levels of copper are found, it indicates that a bushing is wearing down—allowing the flight team to replace the component before it causes a loss of oil pressure mid-mission.

Conclusion

Loss of oil pressure remains one of the most daunting challenges in the world of high-performance flight technology. Whether caused by the mechanical failure of a pump, the environmental stress of high-altitude flight, or the simple degradation of a rubber seal, the results are almost always the same: a compromised mission and a grounded aircraft.

However, through the integration of advanced sensors, dry-sump engineering, and predictive maintenance analytics, the risks are being mitigated. As we continue to rely on gas-powered and hybrid UAVs for critical infrastructure, search and rescue, and global logistics, the technology used to monitor and maintain oil pressure will remain as vital as the engines themselves. For the flight professional, understanding these systems is not just about mechanics—it’s about ensuring that every take-off is followed by a safe and controlled landing.