The fundamental building blocks of life, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), are often mentioned in the same breath, their molecular dance underpinning the very processes that allow organisms to grow, reproduce, and function. While both are nucleic acids and share a common ancestry in their chemical structure, their roles, structures, and even their chemical compositions present distinct differences that are critical to understanding the intricacies of cellular biology. This exploration will delve into these key divergences, illuminating how these two vital molecules, though related, are far from interchangeable in the grand design of living systems.

The Structural Blueprint: Sugar and Backbone Variations

At the heart of the difference between DNA and RNA lies a subtle yet significant variation in their core molecular structure, specifically in the sugar component and the overall stability of their helical frameworks. These seemingly minor alterations have profound implications for their respective functions within the cell.

The Sugar Moiety: Deoxyribose vs. Ribose

The most fundamental structural distinction between DNA and RNA lies in the type of pentose sugar they contain. DNA, as its name suggests, contains deoxyribose sugar. The prefix “deoxy” signifies the absence of an oxygen atom at the 2′ (pronounced “two prime”) carbon position of the sugar ring. In contrast, RNA utilizes ribose sugar, which possesses a hydroxyl group (-OH) at this same 2′ carbon position.

This seemingly small difference in an oxygen atom has significant consequences. The presence of the hydroxyl group in ribose makes RNA a more reactive molecule compared to DNA. This increased reactivity is crucial for RNA’s diverse, often transient, roles in the cell, such as acting as messengers or catalysts. Deoxyribose, lacking this extra oxygen, confers greater stability to the DNA molecule, making it ideally suited for its primary function as a long-term repository of genetic information. This inherent stability allows DNA to withstand the rigors of cellular life and environmental factors, safeguarding the integrity of the genetic code.

The Backbone of Stability: Phosphate and Sugar Strands

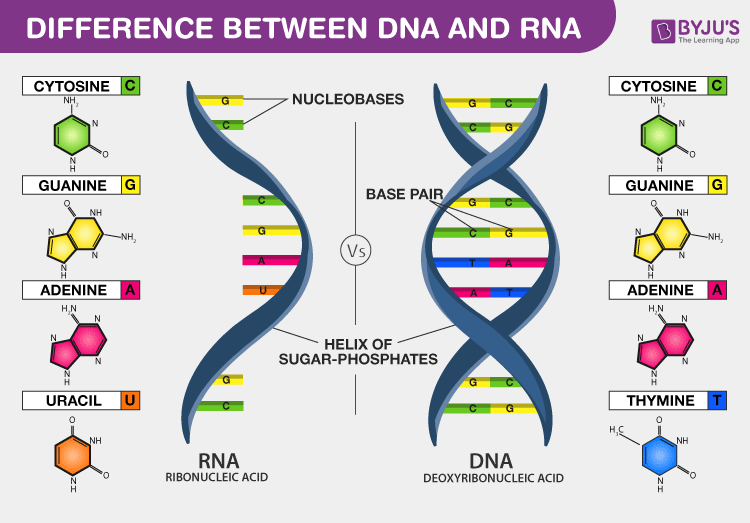

Both DNA and RNA are polymers composed of repeating nucleotide units. Each nucleotide consists of three components: a phosphate group, a sugar molecule (deoxyribose in DNA, ribose in RNA), and a nitrogenous base. These nucleotides link together via phosphodiester bonds, forming a sugar-phosphate backbone.

In DNA, this backbone is formed by alternating deoxyribose sugars and phosphate groups. The absence of the 2′-hydroxyl group in deoxyribose means that the phosphodiester bond in DNA is more resistant to hydrolysis, contributing to its overall stability. DNA typically exists as a double helix, with two complementary strands wound around each other. The sugar-phosphate backbones run along the outer edges of the helix, with the nitrogenous bases paired in the interior.

RNA, on the other hand, generally exists as a single strand. While it can fold upon itself to form complex three-dimensional structures, it lacks the robust double-helical structure characteristic of DNA. The presence of the 2′-hydroxyl group in ribose makes the RNA backbone more susceptible to alkaline hydrolysis. This inherent lability is consistent with RNA’s often temporary roles in the cell. Its single-stranded nature also allows for greater structural flexibility, enabling RNA molecules to adopt a wide array of shapes that are essential for their diverse functions, from enzymatic activity to protein synthesis.

The Alphabet of Life: Nitrogenous Bases and Their Roles

While both DNA and RNA employ four nitrogenous bases, a key distinction lies in one of these bases, fundamentally altering their coding potential and interaction capabilities.

The Quartet of Bases: Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine, and Thymine/Uracil

The nitrogenous bases are the letters in the genetic alphabet. Both DNA and RNA share three of these bases:

- Adenine (A)

- Guanine (G)

- Cytosine (C)

However, there is a crucial difference in the fourth base. DNA utilizes Thymine (T), while RNA uses Uracil (U). Adenine always pairs with Thymine in DNA (A-T), and Guanine always pairs with Cytosine (G-C) via hydrogen bonds, forming the rungs of the DNA ladder. Similarly, in RNA, Adenine can pair with Uracil (A-U), and Guanine with Cytosine (G-C).

The substitution of Uracil for Thymine in RNA is a significant divergence. Uracil is a less complex and energetically less expensive molecule to synthesize than Thymine. This reflects the often transient nature of RNA molecules. As RNA is typically produced when needed and degraded after its function is complete, the evolutionary economy of using Uracil is advantageous. Thymine, with its methyl group, is a more stable base and is crucial for the long-term storage and accuracy of the genetic information housed within DNA.

Base Pairing and Interactions: The Double Helix vs. Single Strands

The base-pairing rules are central to the function of nucleic acids. In DNA, the complementary base pairing (A with T, and G with C) is what allows the double helix to form and maintain its structure. This complementarity is also the basis for DNA replication, where each strand serves as a template for the synthesis of a new complementary strand, ensuring faithful inheritance of genetic information.

In RNA, while base pairing still occurs, it is primarily within a single molecule or between an RNA molecule and a DNA template during transcription. The A-U and G-C pairings dictate how RNA molecules fold into specific three-dimensional structures, which are critical for their function. For instance, messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules fold in specific ways to interact with ribosomes for protein synthesis, and transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules fold into characteristic L-shapes that enable them to carry specific amino acids to the ribosome. The single-stranded nature of RNA, coupled with its ability to form internal base pairs, grants it a remarkable versatility in shape and function that the rigid double-stranded DNA helix does not possess.

Functional Divergence: Information Storage vs. Molecular Workhorses

The structural and chemical differences between DNA and RNA directly translate into their vastly different roles within the cell. DNA is the master blueprint, while RNA acts as a versatile executor of instructions.

DNA: The Permanent Genetic Archive

DNA’s primary function is to serve as the genome, the complete set of genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth, and reproduction of all known organisms and many viruses. Its double-helical structure and the chemical stability conferred by deoxyribose and the A-T pairing make it exceptionally well-suited for this role. DNA resides predominantly in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells, protected from the cellular machinery that might damage it.

The genetic information encoded in DNA is organized into genes, which are segments of DNA that carry the instructions for building specific proteins or functional RNA molecules. This information is replicated with remarkable fidelity during cell division, ensuring that daughter cells receive an accurate copy of the genome. DNA is essentially a stable, long-term storage medium for the hereditary material passed down from generation to generation.

RNA: The Dynamic Executors of Genetic Information

RNA molecules, in contrast to DNA, are far more diverse in their functions and generally more transient in their existence. They are the key players in the expression of genetic information, translating the DNA code into the functional components of the cell, primarily proteins. There are several major types of RNA, each with a specialized role:

- Messenger RNA (mRNA): Carries the genetic code from DNA in the nucleus to the ribosomes in the cytoplasm, where protein synthesis takes place.

- Transfer RNA (tRNA): Acts as an adaptor molecule, carrying specific amino acids to the ribosome and matching them to the codons on the mRNA sequence during protein synthesis.

- Ribosomal RNA (rRNA): A structural and catalytic component of ribosomes, the cellular machinery responsible for protein synthesis.

- Regulatory RNAs: This encompasses a broad category of RNAs that do not code for proteins but play crucial roles in gene regulation. Examples include microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which can silence gene expression, and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which have diverse regulatory functions.

The inherent reactivity of RNA, due to the ribose sugar, and its single-stranded nature allow it to adopt complex shapes and interact with a variety of cellular molecules, enabling its diverse enzymatic and regulatory functions. RNA is not just a messenger; it is an active participant in the complex molecular ballet of cellular life.

Location and Stability: Nucleus vs. Cytoplasm and Beyond

The physical location and inherent stability of DNA and RNA within the cell further underscore their differing roles.

DNA’s Fortress: The Nucleus

In eukaryotic cells, the vast majority of DNA is located within the nucleus, a membrane-bound organelle that acts as the cell’s control center. This compartmentalization protects the precious genetic material from potential damage by cytoplasmic enzymes and other cellular stresses. Small amounts of DNA are also found in mitochondria and chloroplasts (in plant cells), reflecting their evolutionary origins as endosymbiotic organelles. The nuclear location of DNA ensures its stability and its role as the central repository of genetic information, accessible for replication and transcription but largely shielded from the direct activities of protein synthesis.

RNA’s Ubiquitous Presence and Transient Nature

RNA molecules are far more mobile and transient within the cell. mRNA, once transcribed in the nucleus, moves to the cytoplasm to interact with ribosomes. tRNA molecules also operate in the cytoplasm, delivering amino acids. rRNA is a fundamental component of ribosomes, which are found in the cytoplasm and on the endoplasmic reticulum.

Furthermore, RNA plays roles in various cellular processes beyond protein synthesis. Some viruses are composed entirely of RNA, using it as their genetic material. Moreover, the discovery of catalytic RNA molecules, known as ribozymes, has revealed that RNA can act as an enzyme, performing chemical reactions essential for cellular life. The relatively short lifespan of many RNA molecules, coupled with their presence in multiple cellular locations, highlights their dynamic and functional roles in the ongoing business of the cell, rather than as permanent archives.

In conclusion, while DNA and RNA share a common molecular heritage, their differences in sugar composition, base pairing, structural integrity, and cellular location dictate their distinct and complementary roles in the symphony of life. DNA stands as the stable, enduring blueprint, safeguarding the genetic legacy. RNA, in its varied forms, acts as the dynamic messenger, the intricate regulator, and the catalytic worker, translating the genetic code into the very fabric of cellular function. Understanding these fundamental distinctions is crucial for unraveling the complexities of molecular biology and appreciating the elegant mechanisms that govern all living organisms.