In the rapidly evolving landscape of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the terminology we use to describe performance is increasingly borrowing from the biological world. When we discuss “high BUN and creatinine” within the context of high-end drone technology and innovation, we are not referring to human renal function, but rather to the sophisticated diagnostic metrics that determine the “metabolic” health of an autonomous system. In the world of Tech & Innovation—specifically remote sensing, AI-driven flight, and edge computing—these terms serve as metaphors for two critical indicators: Battery Utility Network (BUN) efficiency and Compute-Resources and Task-Integration-Efficiency (Creatinine).

Understanding these metrics is vital for engineers and enterprise operators who manage fleets of autonomous drones. High readings in these internal diagnostics often signal that the drone’s “internal organs”—its ESCs (Electronic Speed Controllers), NPUs (Neural Processing Units), and power distribution boards—are under significant stress. This article explores what these high levels mean for drone longevity, mission success, and the future of autonomous predictive maintenance.

The Biometrics of Flight: Monitoring Internal Diagnostic Telemetry

Modern drones are no longer simple mechanical flyers; they are complex, data-driven robots that process gigabytes of information per second. To ensure these machines function at peak performance, developers have implemented internal diagnostic telemetry that mirrors biological monitoring.

Understanding the Drone’s “Metabolic” Rate

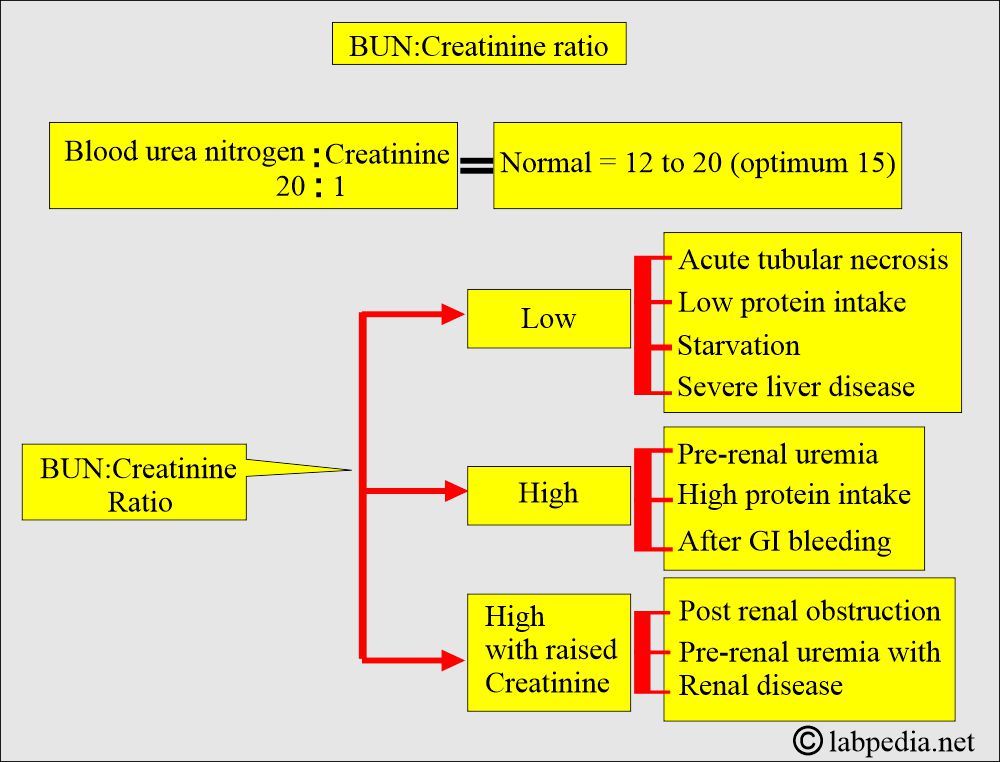

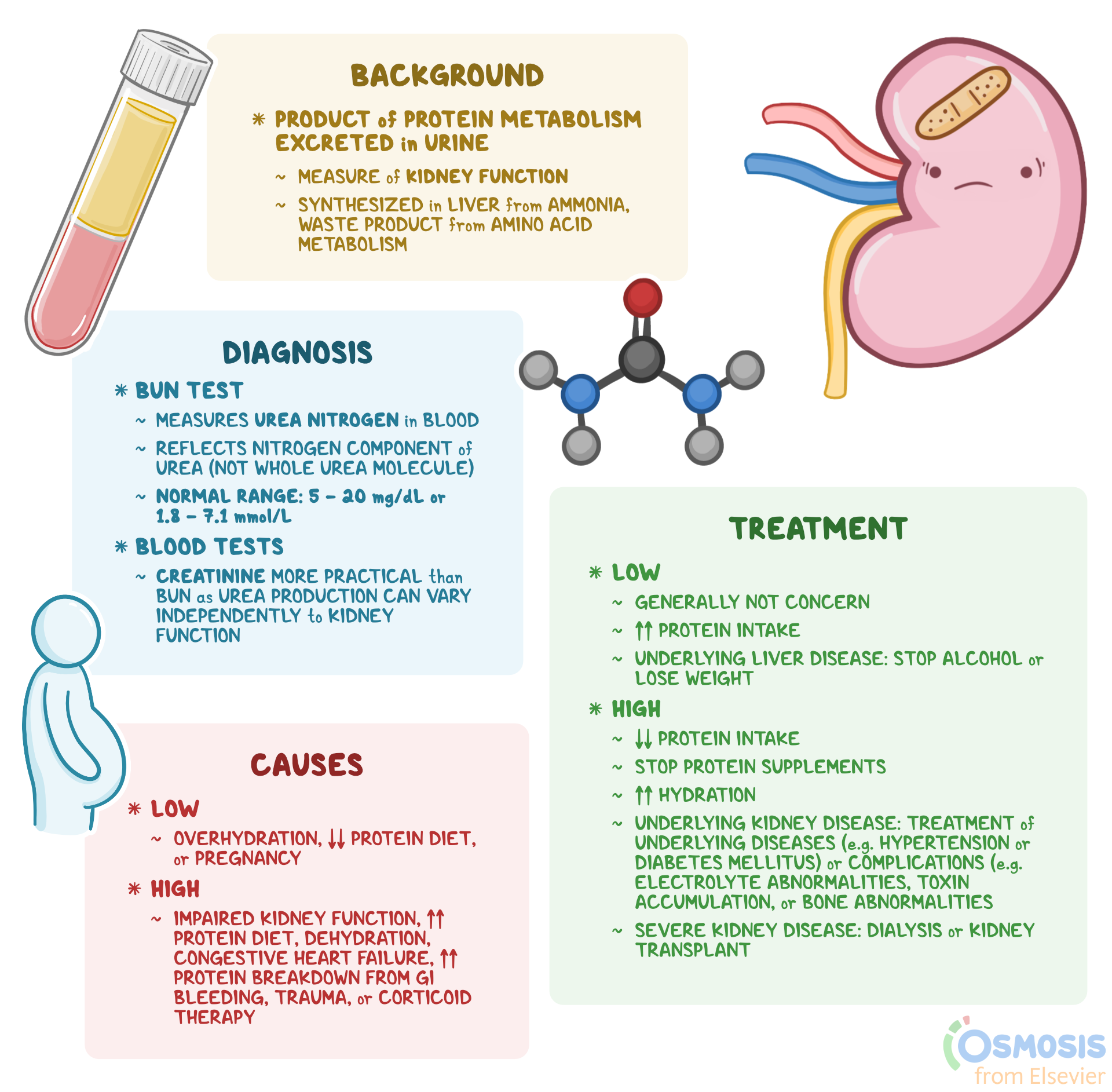

Just as a biological organism requires a balanced metabolism to convert fuel into energy without producing excessive waste, a drone must convert stored electrical energy into mechanical thrust and computational output. The “metabolic rate” of a drone refers to the efficiency of this energy conversion. When we see high “BUN” or “Creatinine” equivalents in our telemetry logs, it suggests that the system is working harder than it should to achieve standard flight parameters. This inefficiency often results in thermal buildup, reduced flight times, and, in severe cases, catastrophic hardware failure.

The Role of Real-Time Diagnostic Algorithms

Innovation in the drone space has led to the development of Real-Time Diagnostic Algorithms (RTDA). These AI-driven layers sit atop the flight controller, constantly “sampling” the digital bloodstream of the UAV. They monitor current draw, voltage sag, and CPU cycle latency. By establishing a baseline of “healthy” telemetry, these systems can alert operators to spikes in “waste products”—the digital noise and heat generated by inefficient processing or mechanical friction.

High “BUN” Equivalents: Analyzing Power Distribution and Thermal Throttling

In our technical nomenclature, “BUN” stands for the Battery Utility Network. This metric tracks the relationship between the power source and the distribution of energy across the drone’s various subsystems. A “high BUN” reading indicates that the power distribution system is experiencing high resistance or excessive demand that it cannot efficiently filter.

Battery Utility and Network Stress

When an autonomous drone is equipped with heavy remote sensing payloads—such as LiDAR or hyperspectral sensors—the power draw is immense. High BUN readings often occur when the Battery Management System (BMS) detects that the cells are discharging at a rate that exceeds their C-rating, or when the distribution board is generating electromagnetic interference (EMI) due to high current throughput. This “nitrogenous waste” of the electrical system leads to voltage ripples, which can destabilize sensitive GPS and IMU sensors.

Identifying Over-Voltage and Power Surge Patterns

Innovation in power electronics has introduced “smart” ESCs that can report back on their own health. A high “BUN” reading in a specific motor branch often points to a failing bearing or a slightly warped propeller, forcing the motor to draw more current to maintain the RPM commanded by the flight controller. For autonomous fleets, recognizing these spikes early is the difference between a routine landing and an expensive mid-air motor burnout.

High “Creatinine” in Flight: Compute Saturation and Sensor Processing Latency

If BUN represents the power system, then “Creatinine” represents the efficiency of the drone’s “kidneys”—its onboard processors. In the context of Category 6 Tech & Innovation, high Creatinine refers to Compute-Resources and Task-Integration-Efficiency. It measures the buildup of unprocessed data packets and the latency in the drone’s decision-making loop.

The Bottleneck of Edge Computing

As drones move toward full autonomy, they rely heavily on edge computing to process AI-follow modes and obstacle avoidance in real-time. High Creatinine levels occur when the NPU (Neural Processing Unit) is saturated. If the drone is flying through a complex environment, such as a dense forest or a busy construction site, the amount of visual data coming from the stereo cameras can overwhelm the processor. This creates a “buffer bloat” where the drone is making decisions based on data that is several milliseconds old—a dangerous state for high-speed flight.

Data Congestion and Internal Communication Lag

In sophisticated mapping drones, the internal communication bus (often using CAN bus or similar protocols) can become congested. When “Creatinine” levels are high, it means the metadata from the sensors is not being stamped and saved quickly enough. This “waste product” of data congestion leads to dropped frames in a mapping mission or “stuttering” in the drone’s autonomous path-planning. Innovators are solving this by using faster bus architectures and optimized AI models that require fewer “compute cycles” to achieve the same level of environmental awareness.

Diagnostic Tools for Predictive Maintenance in Remote Sensing

The ability to interpret high BUN and Creatinine levels is the cornerstone of modern predictive maintenance. In industrial applications, where drones are used for inspecting power lines or offshore wind turbines, “downtime” is the enemy.

Leveraging AI for Anomaly Detection

Tech leaders are now integrating “Health and Usage Monitoring Systems” (HUMS) into drone firmware. These systems use machine learning to analyze historical flight data. If a drone’s BUN levels have been steadily rising over ten flights, the AI can predict a failure of the power distribution board before it happens. This move from reactive to proactive maintenance is a major shift in the UAV industry, allowed by the granular tracking of these “internal” metrics.

Digital Twins and Performance Benchmarking

Another innovative approach is the use of “Digital Twins.” By creating a virtual replica of the drone in a simulation environment, engineers can run “stress tests” to see what causes high BUN and Creatinine readings. Operators can then compare their real-world flight data against the Digital Twin’s baseline. If the real-world drone shows higher “Creatinine” (compute latency) than the digital model under the same conditions, it indicates a firmware bug or hardware degradation that needs immediate attention.

Optimization Strategies: Restoring Equilibrium to Drone Systems

When a system displays high BUN and Creatinine equivalents, the goal is to bring the drone back to a state of “homeostasis.” This requires a mix of hardware adjustments and software optimizations.

Firmware Optimization and Load Balancing

Just as a medical professional might recommend a change in diet, a drone engineer will look at the “code diet” of the UAV. Optimizing the flight stack (such as ArduPilot or PX4) can significantly lower compute latency. By offloading certain non-critical tasks to different processor cores or reducing the frequency of non-essential sensor polling, engineers can “flush out” the Creatinine buildup and return the drone to a responsive state. Load balancing across the CPU ensures that the obstacle avoidance system always has the priority it needs.

Hardware Cooling and Structural Integrity Checks

Heat is the primary driver of electronic inefficiency. High BUN levels are often exacerbated by thermal throttling. Innovation in drone chassis design—such as using carbon fiber frames that act as heat sinks or integrating active cooling fans for the compute module—can help lower these readings. Furthermore, ensuring that the drone’s mechanical “joints” (the motors and bearings) are clean and lubricated reduces the physical resistance, thereby lowering the power draw and the “BUN” levels of the battery network.

The Future of Autonomous System Diagnostics

As we look toward the future of drone technology, the complexity of these machines will only increase. We are entering an era where drones will be expected to operate for weeks at a time from “drone-in-a-box” stations without human intervention. In such scenarios, the ability of the drone to self-diagnose high “BUN and Creatinine” levels is paramount.

The innovation lies in the integration of autonomous “healing” protocols. Imagine a drone that, upon detecting a rise in its internal compute latency (Creatinine), automatically adjusts its flight speed to reduce the data processing load, or switches to a more efficient flight path to preserve battery health (BUN). This level of systemic awareness will be what separates consumer gadgets from true enterprise-grade autonomous robots.

In conclusion, “high BUN and creatinine” in the drone world are the vital signs of the digital age. By monitoring the Battery Utility Network and Compute-Resource Efficiency, we can ensure that our autonomous systems remain “healthy,” efficient, and ready to tackle the complex challenges of remote sensing and AI-driven flight. The professional drone operator of tomorrow won’t just be a pilot; they will be a system “physician,” interpreting the complex telemetry of high-tech machines to keep them soaring safely.