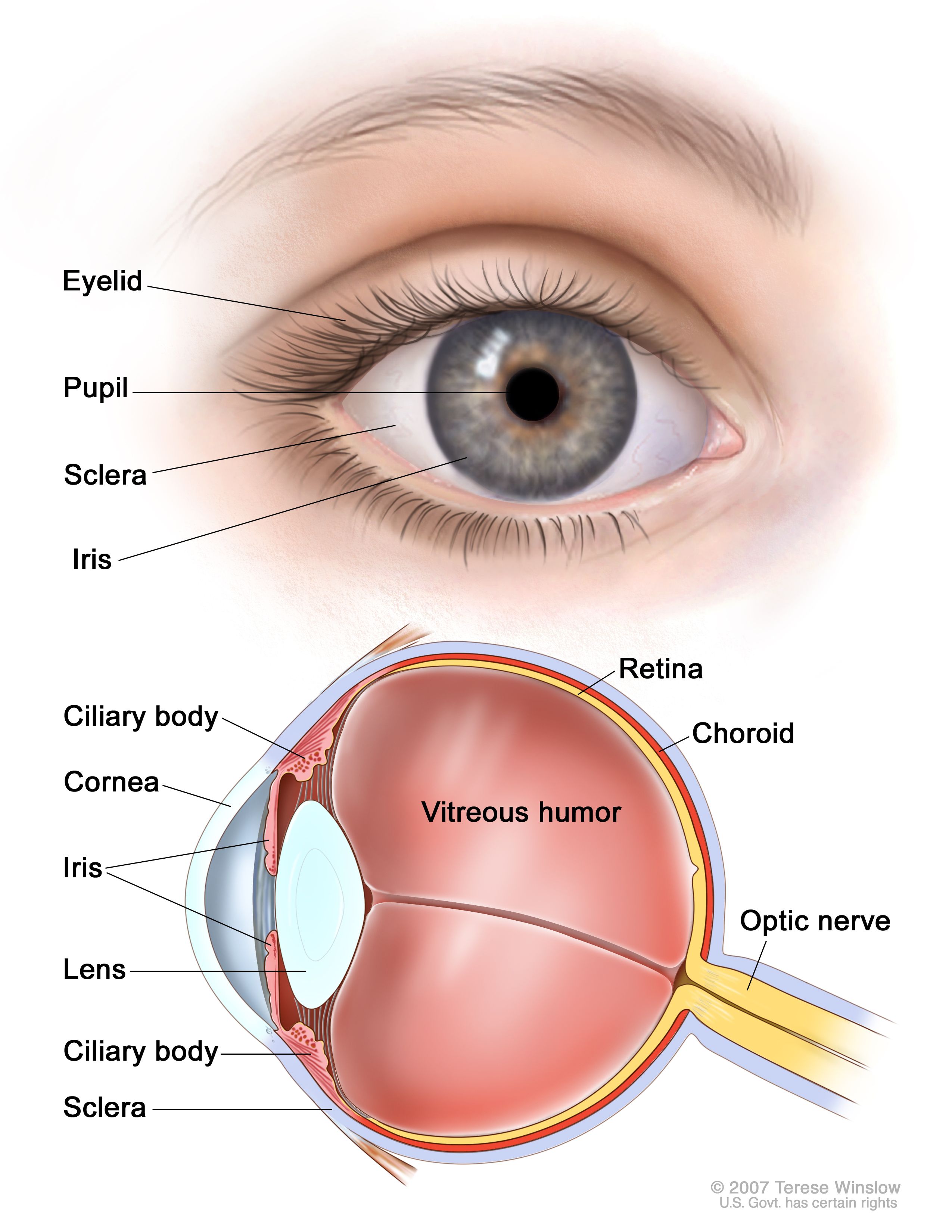

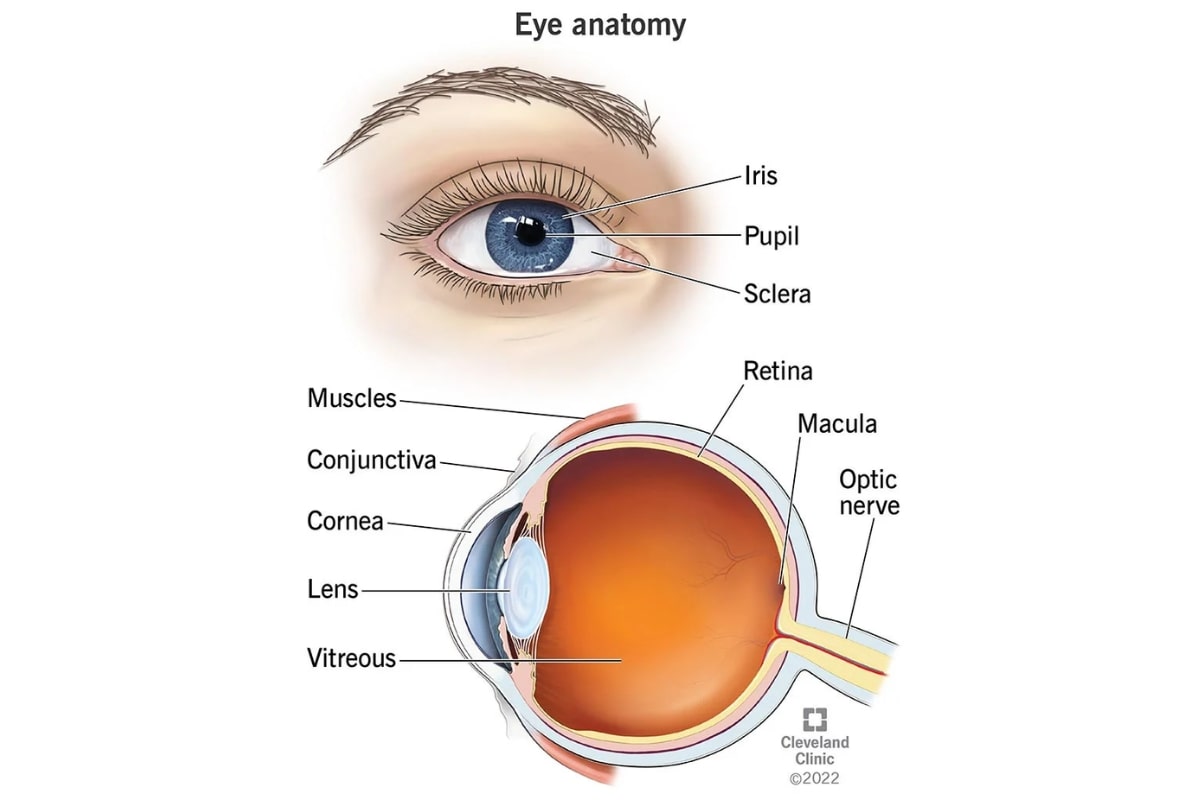

In the world of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the camera is frequently referred to as the “eye” of the drone. Just as the human eye relies on a biological lens to refract light onto the retina, a drone’s imaging system depends on a sophisticated assembly of glass or plastic elements—the lens—to project an image onto a digital sensor. While we often discuss flight times, battery capacities, and transmission ranges, the lens is arguably the most critical component for any pilot involved in photography, cinematography, or industrial inspection. It is the gatekeeper of light, the arbiter of clarity, and the primary factor that determines the visual “character” of the footage captured from the sky.

Understanding what the lens is within the context of drone technology requires a deep dive into optical physics, material science, and digital integration. This article explores the anatomy, functionality, and technological evolution of the drone’s eye.

The Anatomy of the Aerial Eye: How Drone Lenses Work

To understand the “lens in the eye” of a drone, one must first view it not as a single piece of glass, but as a complex optical system. Most modern drones utilize a “prime” or “zoom” lens configuration consisting of multiple individual elements arranged in groups. These elements work in harmony to correct distortions and ensure that light hits the sensor with absolute precision.

The Convergence of Light and Sensor

At its most basic level, the lens performs a single task: it takes divergent light rays from the environment and converges them into a sharp focal point on the camera’s sensor. In the “eye” of the drone, this sensor (typically a CMOS or CCD chip) acts as the retina. The quality of this convergence determines the sharpness of the image. High-quality lenses use aspherical elements to reduce spherical aberration—a common issue where light rays at the edge of the lens focus at different points than those in the center, causing blurriness. In drone photography, where the subject is often several hundred feet away, the precision of this focus is what separates a professional-grade aerial map from a blurry snapshot.

Fixed vs. Variable Focal Lengths

The “eye” of a drone can be either specialized or versatile. Small, consumer-grade drones often feature fixed-focal-length lenses (prime lenses). These are optimized for a specific field of view (FOV), usually wide-angle, to capture expansive landscapes. Because they have fewer moving parts, they are lighter and more durable—essential traits for flight. Conversely, high-end platforms like the DJI Mavic 3 or the Inspire series utilize variable focal length lenses (zoom lenses). These allow the “eye” to narrow its focus, bringing distant objects closer without moving the aircraft. This is achieved by physically shifting the distance between lens elements within the barrel, a feat of miniaturized engineering that must withstand the vibrations and G-forces of flight.

Key Characteristics of High-Performance Drone Lenses

Not all “eyes” are created equal. The performance of a drone lens is dictated by several key specifications that influence how it handles light and detail. For professionals, these specs are the benchmarks used to select the right tool for a specific mission.

Aperture and Light Sensitivity

The aperture is the “pupil” of the drone’s eye. It is the opening through which light enters the camera. Measured in f-stops (such as f/2.8 or f/11), the aperture controls two vital aspects of imaging: exposure and depth of field. In low-light environments, such as during dawn or dusk “blue hour” shoots, a wide aperture (a lower f-number) is crucial. It allows more light to reach the sensor, reducing the need for high ISO settings that introduce digital noise. Furthermore, adjustable apertures on professional drones allow pilots to control the depth of field, enabling that cinematic “bokeh” effect where the subject is sharp against a beautifully blurred background.

Resolution and Sharpness: Beyond the Megapixel

While marketing departments often focus on megapixels, the lens is what actually delivers that resolution. A 48-megapixel sensor is useless if the lens in front of it is “soft” or low-quality. Sharpness is a measure of how well the lens can distinguish between fine details, such as the individual leaves on a tree or the structural cracks in a bridge inspection. High-end drone lenses are engineered to provide “edge-to-edge” sharpness, ensuring that the corners of the frame are just as clear as the center. This is particularly vital in photogrammetry and mapping, where every pixel across the entire image is used to generate 3D models.

Advanced Optical Technologies in Modern UAVs

As drone technology has matured, the “lens in the eye” has benefited from innovations originally developed for high-end cinema cameras and space-based telescopes. These advancements allow drones to capture imagery that was once impossible for such small devices.

Low Dispersion Glass and Coatings

One of the greatest enemies of aerial imaging is chromatic aberration—a “purple fringing” effect that occurs when a lens fails to focus all colors of light at the same point. To combat this, manufacturers use Extra-low Dispersion (ED) glass. This specialized material has unique refractive properties that keep colors aligned. Additionally, modern drone lenses are treated with multi-layered nano-coatings. These microscopic layers reduce “flare” and “ghosting,” which are common when flying toward the sun. For an aerial filmmaker, these coatings are what allow for the capture of a crisp sunset without losing contrast to internal reflections within the lens.

The Role of the Gimbal in Optical Stability

While not technically part of the glass elements, the gimbal is the “socket” that holds the eye. In drone photography, the lens must remain perfectly still even as the aircraft buffets in the wind. A three-axis gimbal uses brushless motors to compensate for pitch, roll, and yaw in real-time. This mechanical stabilization works in tandem with the lens’s own optical properties to ensure that the light hitting the sensor is not blurred by movement. In some high-end systems, the lens also features internal Optical Image Stabilization (OIS), where elements move slightly to counteract high-frequency vibrations that the gimbal might miss.

Choosing the Right “Eye” for Your Mission

Selecting a drone is often a matter of selecting a lens. Depending on the application—be it creative filmmaking, agricultural monitoring, or infrastructure inspection—the requirements for the “eye” change significantly.

Wide-Angle for Surveying and Landscapes

Most standard drones come equipped with a wide-angle lens, typically equivalent to a 24mm or 28mm lens on a full-frame camera. This provides a broad field of view, making it the ideal choice for capturing the scale of a mountain range or the layout of a construction site. In surveying, a wide lens allows the drone to cover more ground in fewer passes, increasing efficiency. However, the trade-off is often “barrel distortion,” where straight lines (like the horizon) appear slightly curved. High-quality drone lenses include rectilinear corrections to ensure that even at wide angles, the world looks as it should.

Telephoto Lenses for Inspection and Wildlife

In recent years, “dual-camera” or “triple-camera” drones have become the industry standard for professional use. These units include a telephoto lens alongside the standard wide-angle eye. A telephoto lens is essential for “non-destructive” inspections—allowing a pilot to see a high-voltage power line or a cell tower component from a safe distance. In wildlife cinematography, the telephoto lens allows the “eye” to zoom in on an animal without the drone’s noise disturbing its natural behavior. This versatility turns the drone into a multi-functional tool capable of both macro-level observation and micro-level detail.

The Future of Drone Optics: AI and Computational Imaging

The concept of the “lens in the eye” is currently undergoing a digital revolution. We are moving away from purely physical optics toward a hybrid of glass and silicon. As drones become smarter, the way they interpret the light entering the lens is changing.

Computational photography allows the drone’s internal processor to “correct” the lens in real-time. Software can remove distortion, sharpen edges, and even merge multiple exposures to create a higher dynamic range (HDR) than the physical lens could achieve on its own. Furthermore, AI-driven lenses are beginning to emerge. These systems can recognize subjects and adjust focus or zoom automatically to keep a moving target perfectly framed.

As we look to the future, the “eye” of the drone will likely become even more specialized. We are already seeing the integration of thermal lenses—which see heat rather than light—and multispectral lenses used in precision agriculture to “see” the health of crops through invisible light frequencies. Regardless of the spectrum, the fundamental principle remains: the lens is the most vital bridge between the physical world and the digital data we collect from the sky. Without a high-quality lens, a drone is merely a flying machine; with it, it becomes a powerful, perceptive eye capable of transforming our perspective of the earth.