Stateful Packet Inspection (SPI), often referred to as dynamic packet filtering, represents a significant evolution in network security beyond the capabilities of stateless packet filtering. While stateless methods examine each packet in isolation, SPI maintains a record of active connections and their associated state. This fundamental difference allows SPI firewalls to make more intelligent and context-aware decisions about which traffic to permit or deny. Understanding SPI is crucial for anyone involved in network management, cybersecurity, or even for individuals seeking a deeper comprehension of how their online communications are secured.

At its core, SPI addresses a critical limitation of stateless inspection: the inability to understand the context of a packet within a larger communication stream. Imagine a simple conversation. A stateless inspector would hear individual words without understanding if they are part of a question, an answer, or a statement. SPI, however, is like having the full transcript of the conversation, allowing for a much richer understanding of meaning and intent. This context-awareness is what empowers SPI to provide a more robust and effective security posture for networks of all sizes.

The Evolution from Stateless to Stateful Inspection

The development of SPI was a direct response to the growing complexity and inherent vulnerabilities of earlier network security models. To appreciate the significance of SPI, it’s essential to understand its predecessor and the limitations it presented.

Stateless Packet Filtering: A Foundational but Limited Approach

Stateless packet filtering, the earliest form of firewall technology, operates on a packet-by-packet basis. Each incoming and outgoing network packet is examined against a predefined set of rules, often referred to as an Access Control List (ACL). These rules typically inspect basic packet header information such as:

- Source IP Address: The origin of the packet.

- Destination IP Address: Where the packet is intended to go.

- Source Port: The application port on the sending device.

- Destination Port: The application port on the receiving device.

- Protocol: The communication standard being used (e.g., TCP, UDP, ICMP).

If a packet matches a rule in the ACL that permits it, the packet is allowed to pass. If it matches a rule that denies it, or if no rule permits it, the packet is dropped. The critical characteristic of stateless filtering is that it treats every packet as an independent entity, oblivious to any previous packets exchanged between the same hosts or applications.

Limitations of Stateless Inspection

While simple and computationally inexpensive, stateless packet filtering suffers from several significant drawbacks:

- Lack of Context: The most glaring limitation is its inability to understand the state of a connection. For example, in a TCP connection, there are distinct phases: establishing the connection (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK), data transfer, and tearing down the connection (FIN, ACK). A stateless firewall, by default, would have to allow incoming packets for a TCP session without knowing if they are part of an authorized, already established connection or an unsolicited attempt to initiate one.

- Vulnerability to Spoofing: Because it doesn’t track connection states, stateless firewalls can be susceptible to IP spoofing attacks. An attacker could forge packets with legitimate-looking source IP addresses and port numbers, which might be allowed by the stateless rules.

- Complexity in Configuration for Stateful Services: To secure complex protocols that involve dynamic port assignments or multiple connections (like FTP), stateless firewalls require extensive and often intricate rule sets. This can lead to misconfigurations and security gaps.

- Inability to Detect Malicious Payloads: Stateless inspection primarily focuses on packet headers. It has no mechanism to examine the actual data payload of a packet for malicious content or anomalies.

These limitations highlighted the need for a more sophisticated approach to network security, one that could understand the flow of information and make more granular, context-dependent decisions.

The Emergence of Stateful Packet Inspection

Stateful Packet Inspection emerged as the solution to the shortcomings of stateless filtering. SPI fundamentally changes how firewalls operate by introducing the concept of a “state table.” This table acts as a memory for the firewall, keeping track of all active network connections.

How Stateful Packet Inspection Works

When a new connection is initiated (e.g., a TCP SYN packet), the SPI firewall examines it against its rule set. If the packet is permitted, the firewall not only allows it to pass but also creates an entry in its state table for this new connection. This entry typically includes details such as:

- Source IP Address and Port

- Destination IP Address and Port

- Protocol

- Connection State: (e.g., SYNSENT, ESTABLISHED, FINWAIT)

- Sequence Numbers (for TCP): Critical for ensuring packets arrive in the correct order.

- Timestamps and other connection-specific data.

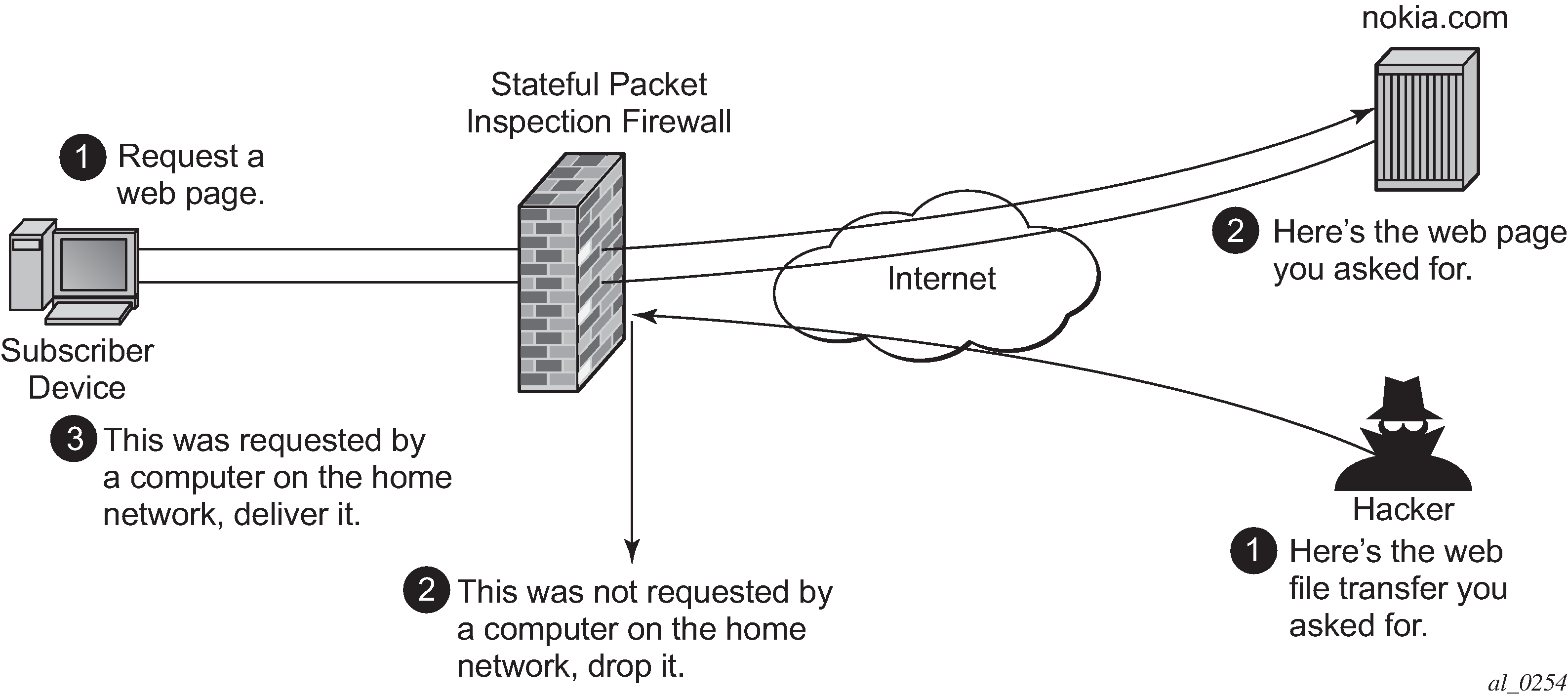

As subsequent packets arrive for that connection, the firewall consults its state table. Instead of re-evaluating the packet against the entire ACL, it checks if the packet is consistent with an existing, authorized connection in the state table.

- Valid Incoming Packets: If an incoming packet matches an entry in the state table for an established connection, it is allowed to pass without needing to match an explicit inbound rule. This is because the firewall already knows this traffic is expected and legitimate.

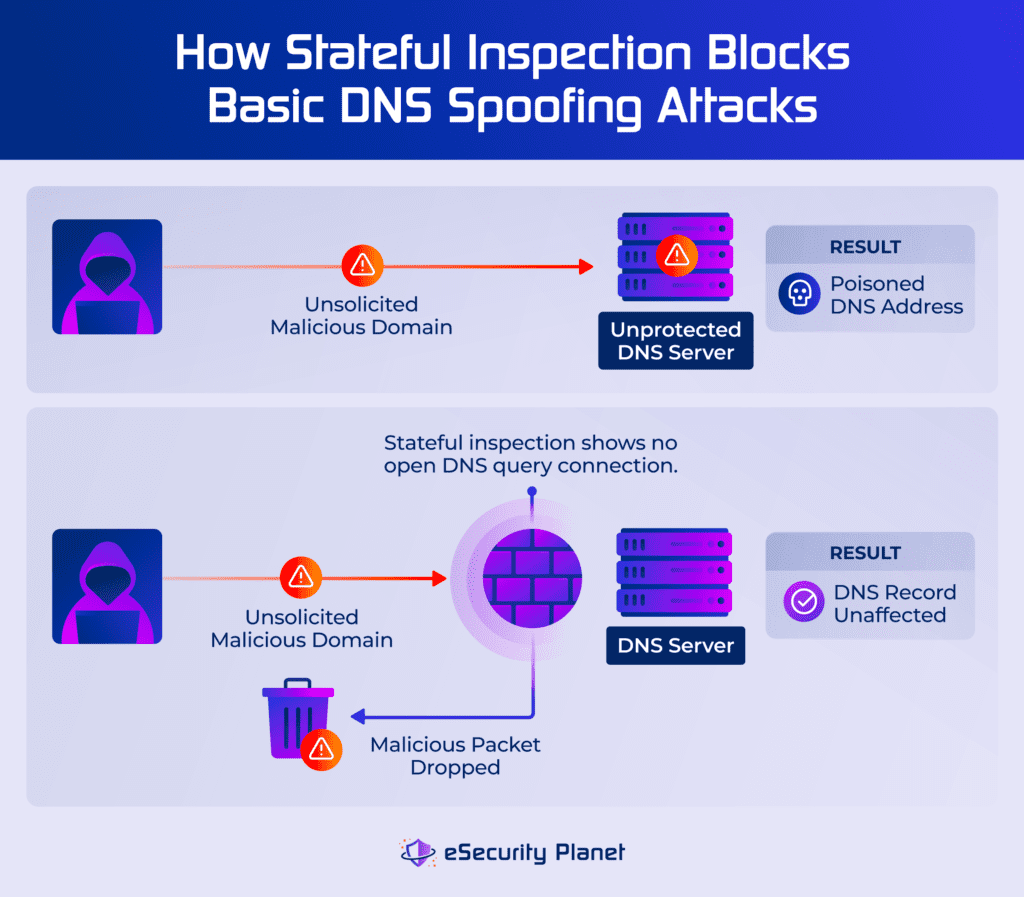

- Unsolicited Incoming Packets: If an incoming packet does not have a corresponding entry in the state table, the firewall treats it as unsolicited and potentially malicious. It then applies the configured ruleset to determine if this new, uninitiated connection should be permitted. Typically, unless there’s a specific rule allowing inbound connections on certain ports, these will be denied.

- Outbound Connection Tracking: Similarly, when an outbound connection is established, its state is recorded. This allows the firewall to permit the return traffic for that established connection, even if there isn’t a specific rule permitting inbound traffic from the external network.

Key Advantages of SPI

The stateful nature of SPI provides several significant advantages over stateless filtering:

- Enhanced Security: By understanding connection states, SPI firewalls can more effectively block unsolicited incoming traffic and prevent many types of attacks, such as IP spoofing and certain denial-of-service (DoS) attacks.

- Simplified Rule Management: For common protocols like TCP, administrators don’t need to create explicit rules for every possible inbound response. The firewall automatically permits legitimate return traffic for established connections.

- Support for Complex Protocols: Protocols that use dynamically assigned ports (e.g., FTP’s data channel) are handled much more gracefully. The SPI firewall can inspect the control channel traffic, identify the port used for data transfer, and dynamically open that port in its state table for the duration of the connection.

- Improved Performance (in some cases): While maintaining the state table requires some overhead, once a connection is established, subsequent packet inspection can be faster as it relies on table lookups rather than a full ACL evaluation.

The Mechanics of Stateful Packet Inspection

Understanding the internal workings of an SPI firewall reveals how it achieves its enhanced security. The core components are the rule set and the state table, working in tandem to control network traffic.

The Firewall Rule Set and its Interaction with State

The firewall’s rule set, much like in stateless filtering, defines the policies for network traffic. However, in SPI, the rule set is primarily used to:

- Approve or Deny the initiation of new connections: Rules dictate which protocols, source/destination IPs and ports are allowed to start a new communication session. For example, a rule might permit outbound HTTP traffic (port 80) from any internal host to any external web server.

- Define default behaviors for traffic not matching existing states: If a packet arrives and doesn’t correspond to an existing connection in the state table, the rule set determines whether this new, unsolicited traffic is allowed.

- Control management and logging features: Rules can also specify how traffic should be logged or which administrative interfaces are accessible.

The critical difference is that once a connection is approved and its state is recorded, subsequent packets belonging to that established connection are automatically permitted as long as they are consistent with the expected state and sequence. This significantly reduces the burden on administrators to meticulously define every potential traffic flow.

The State Table: The Firewall’s Memory

The state table is the heart of SPI. It dynamically stores information about active network connections. Each entry in the state table represents a unique, ongoing communication session. The information stored includes:

- Connection Identifiers: Source and destination IP addresses, source and destination ports.

- Protocol Type: TCP, UDP, ICMP, etc.

- Connection State: For TCP, this includes states like

SYN_SENT,ESTABLISHED,FIN_WAIT,CLOSE_WAIT, etc. For UDP and ICMP, states are typically simpler, often just indicating an active flow. - Sequence and Acknowledgment Numbers (for TCP): These are crucial for reassembling packets in the correct order and verifying data integrity.

- Timers: Entries in the state table are associated with timeouts. If a connection becomes idle for a predefined period, its entry is removed from the state table, conserving resources and closing off potentially stale connections.

- Application-Layer Gateway (ALG) Information: If the firewall has an ALG enabled for a specific protocol (like FTP), it might store information derived from the application layer to facilitate proper state tracking.

When a packet arrives, the firewall first attempts to match it against an entry in its state table.

- If a match is found: The packet is considered part of an established, trusted connection. The firewall then checks if the packet conforms to the expected state and sequence numbers. If it does, the packet is allowed through.

- If no match is found: The packet is considered to be initiating a new connection or is an unsolicited packet. The firewall then consults its rule set to determine if this new connection attempt is permitted.

The state table is a dynamic entity, constantly updated as connections are established, data is exchanged, and connections are terminated. Its efficient management is key to the performance and security of an SPI firewall.

Application-Layer Gateways (ALGs) and Protocol Awareness

One of the most powerful extensions of SPI is the integration of Application-Layer Gateways (ALGs). While basic SPI understands connection states for protocols like TCP and UDP at the transport layer, many application-level protocols are more complex. They might:

- Use multiple ports dynamically.

- Embed IP addresses or port information within the data payload.

- Have specific command structures that indicate the intent of communication.

ALGs act as protocol-specific proxies or intelligent filters that sit “above” the transport layer. When an ALG is enabled for a particular protocol (e.g., FTP, H.323, SIP), the SPI firewall:

- Inspects the control traffic: It understands the commands and parameters exchanged at the application layer.

- Identifies dynamic port assignments: For example, in FTP, the client initiates a control connection on port 21. The server then might instruct the client to connect to a different, dynamically assigned port for the data transfer. The ALG recognizes this instruction and dynamically opens the appropriate port in the state table for the data connection, even if there isn’t a static rule allowing inbound traffic on that specific port.

- Modifies or sanitizes payloads (in some advanced implementations): Some ALGs can also inspect and, if necessary, modify information within the application payload to ensure security or to facilitate communication across different network environments.

By incorporating ALGs, SPI firewalls can provide granular control and security for a wide range of application protocols that would be very difficult, if not impossible, to secure effectively with stateless inspection or even basic SPI alone. This protocol awareness is crucial for modern network security, where diverse applications constantly communicate across the internet.

Advanced Capabilities and Future Directions

Stateful Packet Inspection continues to evolve, incorporating new techniques and technologies to address the ever-changing threat landscape. Its core principles remain, but its implementation and integration with other security measures are becoming increasingly sophisticated.

Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDPS) Integration

Modern firewalls that employ SPI often integrate with Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) and Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS). While SPI focuses on the validity of connections based on state and rules, IDPS/IPS focus on the content and behavior of the traffic.

- IDPS: These systems monitor network traffic for malicious patterns, known attack signatures, or anomalous behavior. If suspicious activity is detected, an IDS generates an alert.

- IPS: An IPS takes this a step further. When it detects a threat, it can actively intervene, much like a firewall. This can include blocking the offending IP address, resetting the connection, or dropping malicious packets – capabilities that complement and enhance SPI.

The synergy between SPI and IDPS/IPS creates a multi-layered defense. SPI ensures that only legitimate connections are established and maintained, while IDPS/IPS scrutinize the data flowing through those connections for signs of malicious intent. This combination is significantly more effective than either technology alone.

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) is an extension of SPI that goes beyond examining packet headers and basic state information. DPI inspects the actual data payload of the packet. This allows for much more granular control and security analysis, such as:

- Application Identification: DPI can identify specific applications (e.g., BitTorrent, Skype, social media apps) regardless of the ports they use, enabling policies to be applied based on application rather than just port numbers.

- Content Filtering: It can be used to block specific types of content, such as malware, viruses, or inappropriate material, by examining the data within packets.

- Data Loss Prevention (DLP): DPI can detect and prevent sensitive data (e.g., credit card numbers, social security numbers) from leaving the network.

- Protocol Anomaly Detection: By understanding the expected structure of various protocols, DPI can detect deviations that might indicate an attack or misconfiguration.

While DPI offers powerful capabilities, it also introduces challenges. Inspecting the payload of every packet can be computationally intensive, impacting network performance. Furthermore, the increasing use of encryption (SSL/TLS) by many applications makes it difficult for DPI to inspect the payload without man-in-the-middle decryption techniques, which raise privacy and security concerns.

The Future of Stateful Inspection: AI and Machine Learning

The future of network security, including stateful inspection, is increasingly being shaped by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). These technologies offer the potential to automate and enhance many aspects of SPI:

- Behavioral Analysis: AI/ML can analyze vast amounts of network traffic data to learn normal network behavior. Deviations from this baseline can then be identified as potential threats, even if they don’t match known signatures. This is particularly useful for detecting zero-day exploits and novel attacks.

- Automated Policy Optimization: AI can analyze traffic patterns and security events to suggest or automatically implement optimal firewall rules, reducing the burden on administrators and improving security posture.

- Threat Prediction and Proactive Defense: ML models can be trained to predict potential attack vectors and proactively adjust firewall configurations or deploy defenses before an attack materializes.

- Enhanced State Table Management: AI could potentially optimize the management of state tables, dynamically adjusting timeouts and prioritizing critical connections based on real-time threat analysis.

While fully autonomous AI-driven firewalls are still some way off, the integration of AI and ML with stateful packet inspection promises a more intelligent, adaptive, and resilient approach to network security, capable of keeping pace with the evolving and sophisticated threats of the digital age.