In the realm of statistical analysis, understanding the potential for making incorrect conclusions is paramount. Two fundamental types of errors can arise during hypothesis testing: Type I error and Type II error. These concepts are not confined to academic research; they have significant implications across various fields, including the development and deployment of sophisticated technologies.

Within the burgeoning landscape of Tech & Innovation, particularly in areas like autonomous systems, AI-driven decision-making, and advanced sensor technologies, a precise understanding of Type I and Type II errors is crucial for ensuring reliability, safety, and efficacy. Whether it’s a drone navigating complex environments, an AI algorithm interpreting sensor data, or a remote sensing system identifying anomalies, the potential for misclassification or missed detection carries tangible consequences. This article will delve into the nature of Type I and Type II errors, their distinctions, and their profound relevance in the context of technological advancement.

Understanding the Fundamentals of Hypothesis Testing

At its core, hypothesis testing is a statistical method used to make inferences about a population based on sample data. It involves formulating two competing statements about a population parameter: the null hypothesis ($H0$) and the alternative hypothesis ($H1$). The null hypothesis typically represents the status quo or a statement of no effect, while the alternative hypothesis represents what we are trying to find evidence for. The goal of hypothesis testing is to determine whether there is enough statistical evidence in the sample data to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

The Null Hypothesis ($H_0$)

The null hypothesis, denoted as $H0$, is a statement of no effect or no difference. It represents the default assumption that is tested against. For example, in the context of a new AI algorithm designed for obstacle avoidance in drones, the null hypothesis might be that the algorithm does not significantly improve obstacle detection rates compared to existing methods. Or, in a remote sensing application, $H0$ could be that a particular area does not exhibit signs of a specific geological formation. The decision-making process in hypothesis testing is geared towards either rejecting or failing to reject this null hypothesis.

The Alternative Hypothesis ($H_1$)

The alternative hypothesis, denoted as $H1$ or $Ha$, is a statement that contradicts the null hypothesis. It represents the effect, difference, or phenomenon that the researcher is seeking to demonstrate. Continuing the drone example, the alternative hypothesis would be that the new AI algorithm does significantly improve obstacle detection rates. In remote sensing, $H1$ might propose that the area does exhibit the signs of the geological formation of interest. The statistical analysis aims to gather sufficient evidence from the data to support the rejection of $H0$ and, by extension, support $H_1$.

Decision Outcomes and Potential Errors

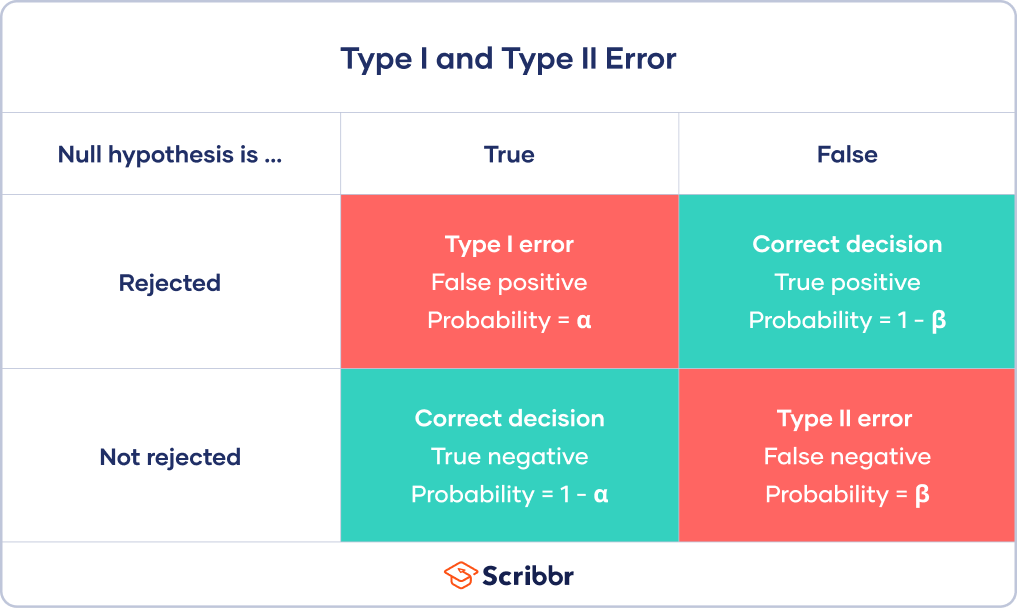

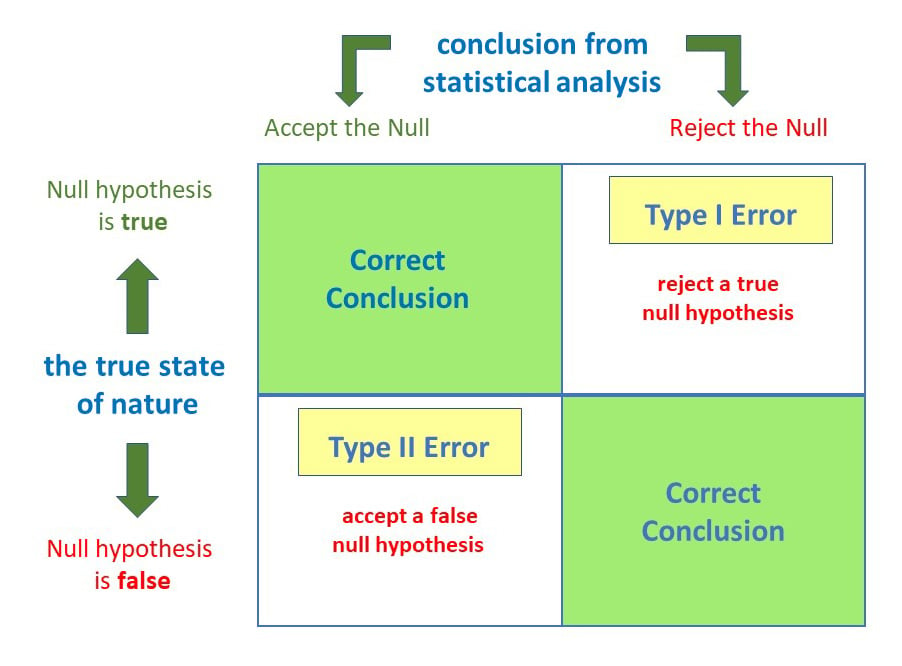

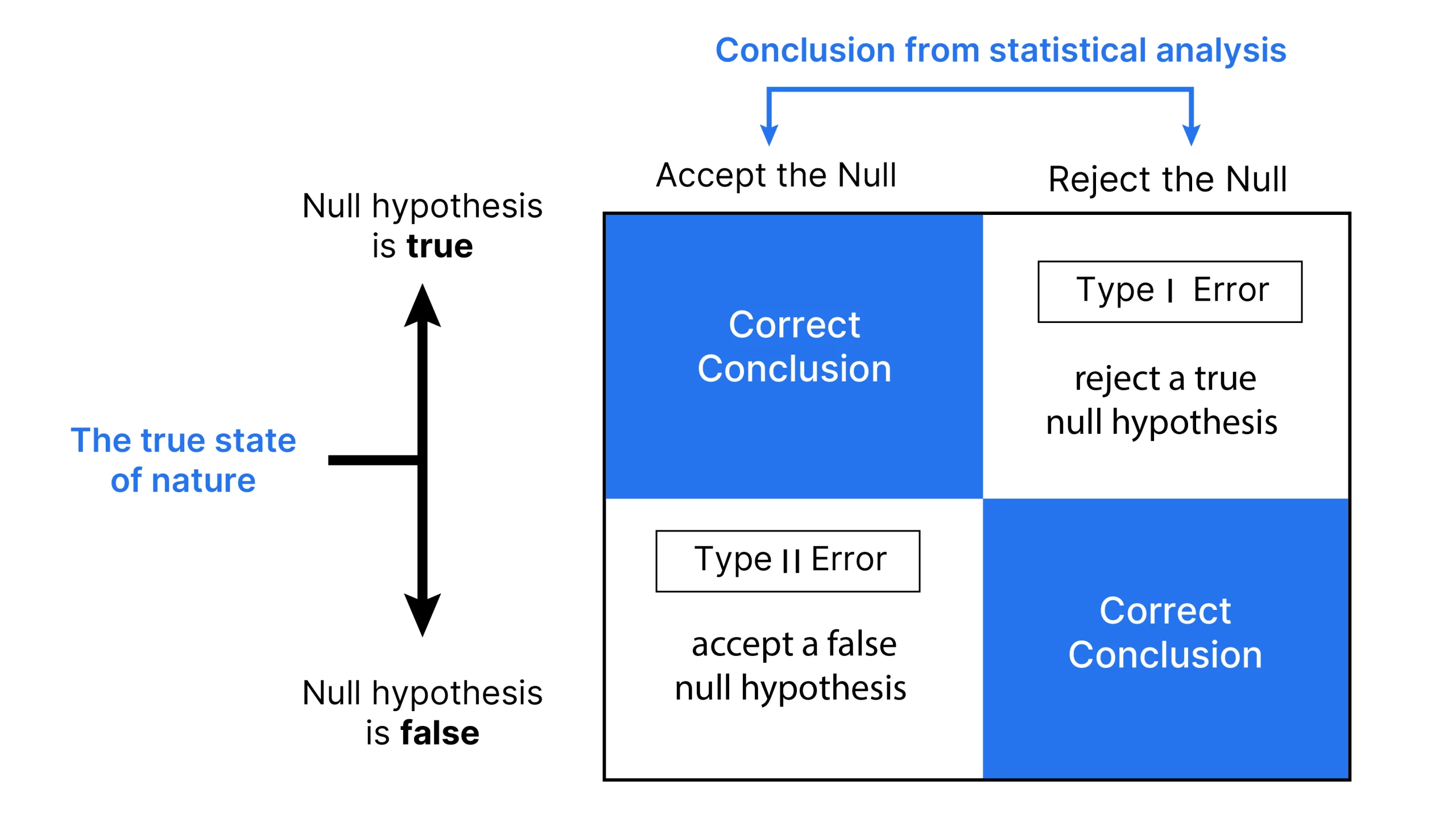

The outcome of a hypothesis test can lead to one of two decisions: either we reject the null hypothesis, or we fail to reject the null hypothesis. These decisions are made based on the observed data and a pre-determined significance level ($alpha$). However, because we are working with sample data rather than the entire population, there is always a possibility that our decision is incorrect. These incorrect decisions are categorized as Type I and Type II errors.

Defining and Distinguishing Type I and Type II Errors

The core of statistical inference lies in correctly evaluating the evidence to make an informed decision about the hypotheses. When this evaluation leads to an erroneous conclusion, it falls into one of two categories: Type I error or Type II error. Understanding the nature of each error is critical for interpreting statistical results and for designing robust technological systems.

Type I Error: The False Positive

A Type I error occurs when we reject the null hypothesis ($H_0$) when it is actually true. In simpler terms, it’s a “false positive” – we conclude that there is a significant effect or difference when, in reality, there isn’t one. The probability of committing a Type I error is denoted by the Greek letter alpha ($alpha$), which is also known as the significance level of the test. When we set a significance level of, for instance, 0.05, we are accepting a 5% risk of making a Type I error.

Implications in Tech & Innovation:

In the context of autonomous systems, a Type I error could manifest as an AI system erroneously detecting an obstacle that isn’t there. For a drone, this might lead to unnecessary evasive maneuvers, potentially causing it to lose its intended path or even crash if the evasive action is poorly executed. In medical diagnostic technology, a Type I error could mean a system falsely identifying a healthy individual as having a disease, leading to unnecessary anxiety and costly follow-up procedures. For AI-driven security systems, a Type I error might trigger a false alarm, causing disruption and a drain on resources.

Type II Error: The False Negative

A Type II error occurs when we fail to reject the null hypothesis ($H_0$) when it is actually false. This is a “false negative” – we conclude that there is no significant effect or difference when, in reality, there is one. The probability of committing a Type II error is denoted by the Greek letter beta ($beta$). The power of a statistical test, which is the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis, is calculated as $1 – beta$. A higher power indicates a lower probability of making a Type II error.

Implications in Tech & Innovation:

A Type II error in autonomous systems could mean an AI system failing to detect a real obstacle. For a drone, this could lead to a collision, damaging the drone and potentially causing harm or damage to property. In a remote sensing application for environmental monitoring, a Type II error might result in failing to detect a nascent environmental hazard, delaying crucial intervention. In fraud detection systems, a Type II error could mean a fraudulent transaction goes unnoticed, leading to financial losses.

The Trade-off Between Type I and Type II Errors

There is an inherent trade-off between Type I and Type II errors. Decreasing the probability of one type of error generally increases the probability of the other, assuming the sample size remains constant. This is because the decision boundary in hypothesis testing is adjusted to control these probabilities.

- Lowering $alpha$ (reducing Type I error risk): If we want to be more certain that we are not falsely claiming an effect (reducing Type I error), we would set a lower significance level (e.g., $alpha = 0.01$ instead of 0.05). However, this makes it harder to reject the null hypothesis, thus increasing the risk of a Type II error (failing to detect a real effect).

- Increasing Power (reducing Type II error risk): To reduce the risk of a Type II error and increase the power of the test, we can increase the sample size. A larger sample size provides more information and reduces the variability of our estimates, making it easier to detect true effects. Alternatively, using a more sensitive statistical test or increasing the significance level (which increases Type I error risk) can also reduce Type II error.

The optimal balance between these errors depends heavily on the specific application and the relative costs of each type of error.

Consequences and Mitigation Strategies in Technological Applications

The presence of Type I and Type II errors in technological systems can have profound and sometimes severe consequences, ranging from minor inefficiencies to catastrophic failures. Therefore, robust strategies for mitigation and management are essential in the design, development, and deployment phases.

Real-World Scenarios and Their Costs

In the domain of Tech & Innovation, particularly with the increasing reliance on artificial intelligence and autonomous decision-making, the costs associated with errors are often amplified.

- Autonomous Vehicles and Drones: A Type I error in an autonomous vehicle’s perception system might cause it to brake unnecessarily for an imaginary obstacle, leading to rear-end collisions. A Type II error could mean failing to detect a pedestrian, resulting in a fatal accident. For drones, misidentifying a safe landing zone (Type I) could lead to an unnecessary abort, while failing to detect an approaching aircraft (Type II) could result in a mid-air collision.

- Medical Devices and Diagnostics: A medical imaging AI that produces a Type I error might flag a benign anomaly as cancerous, leading to invasive biopsies and patient distress. A Type II error from the same system could miss a developing malignancy, delaying life-saving treatment.

- Cybersecurity Systems: A Type I error in a firewall could block legitimate network traffic, disrupting critical operations. A Type II error could allow malware or unauthorized access to penetrate the system, leading to data breaches and significant financial or reputational damage.

- Robotics in Manufacturing: A robot arm that makes a Type I error in its positional accuracy might reject a perfectly good component. A Type II error could lead to a faulty assembly, resulting in product defects and recalls.

Strategies for Minimizing Errors

Mitigating Type I and Type II errors in technological applications requires a multi-faceted approach that often involves statistical rigor, intelligent system design, and rigorous testing.

1. Increasing Sample Size and Data Quality

A fundamental statistical principle for reducing error is to increase the amount and quality of data used for training and validation.

- More Data: Larger datasets provide a more representative picture of the phenomena being modeled, allowing algorithms to learn more robust patterns and reduce the impact of random fluctuations that can lead to errors. In machine learning, this translates to improved model generalization.

- Data Augmentation and Diversity: Beyond sheer quantity, the diversity and representativeness of the data are critical. Ensuring that the training data encompasses a wide range of conditions, scenarios, and potential edge cases helps prevent the model from being overly specialized and prone to errors when encountering novel situations.

- Data Cleaning and Labeling: Inaccurate or biased data can fundamentally undermine the learning process. Rigorous data cleaning, verification, and accurate labeling are essential to ensure that the models are trained on reliable information, thereby reducing the likelihood of both Type I and Type II errors.

2. Optimizing Model Design and Algorithms

The choice of algorithms and the architecture of AI models play a significant role in their error characteristics.

- Algorithm Selection: Different algorithms have varying sensitivities to Type I and Type II errors. For instance, algorithms that are highly sensitive to anomalies might be more prone to Type I errors, while those that are more conservative might be more susceptible to Type II errors. Selecting algorithms appropriate for the specific task and tolerance for each error type is crucial.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: The performance and error profile of a model are heavily influenced by its hyperparameters. Careful tuning of these parameters, often through cross-validation and grid search, can help find an optimal balance between Type I and Type II error rates.

- Ensemble Methods: Combining the predictions of multiple models (ensemble learning) can often lead to more robust and accurate results than any single model. If individual models have different error profiles, the ensemble can leverage their strengths to reduce the overall error rate.

3. Establishing Robust Evaluation Metrics and Thresholds

Beyond simply minimizing errors, it’s important to have appropriate metrics and decision thresholds that align with the application’s risk tolerance.

- Beyond Accuracy: While overall accuracy is important, it can be misleading when dealing with imbalanced datasets or when the costs of Type I and Type II errors are different. Metrics like precision, recall, F1-score, and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves provide a more nuanced understanding of a model’s performance and its error characteristics.

- Cost-Sensitive Learning: In many technological applications, the cost of a Type I error differs significantly from the cost of a Type II error. Cost-sensitive learning algorithms explicitly incorporate these costs into the training process, aiming to minimize the overall expected cost of errors.

- Adaptive Thresholding: For systems that operate in dynamic environments, static decision thresholds may not be optimal. Implementing adaptive thresholding mechanisms that adjust based on current conditions or confidence levels can help balance error rates and improve overall system performance.

In conclusion, Type I and Type II errors are fundamental considerations in statistical inference and are of paramount importance in the field of Tech & Innovation. By understanding their definitions, implications, and developing sophisticated strategies for their mitigation, we can build more reliable, safer, and effective technologies that drive progress and benefit society.