The seemingly simple question of “what is pH in biology” unlocks a vast landscape of scientific inquiry, deeply intertwined with the advancements in technology that allow us to measure, monitor, and manipulate it. While pH, a measure of acidity or alkalinity, is a fundamental chemical property governing biological processes, its understanding and application in modern biological research are inseparable from the sophisticated technological tools that empower scientists. From the microscopic world of cellular functions to the expansive ecosystems of our planet, technological innovation is the key that unlocks the secrets of pH.

The Fundamental Role of pH in Biological Systems

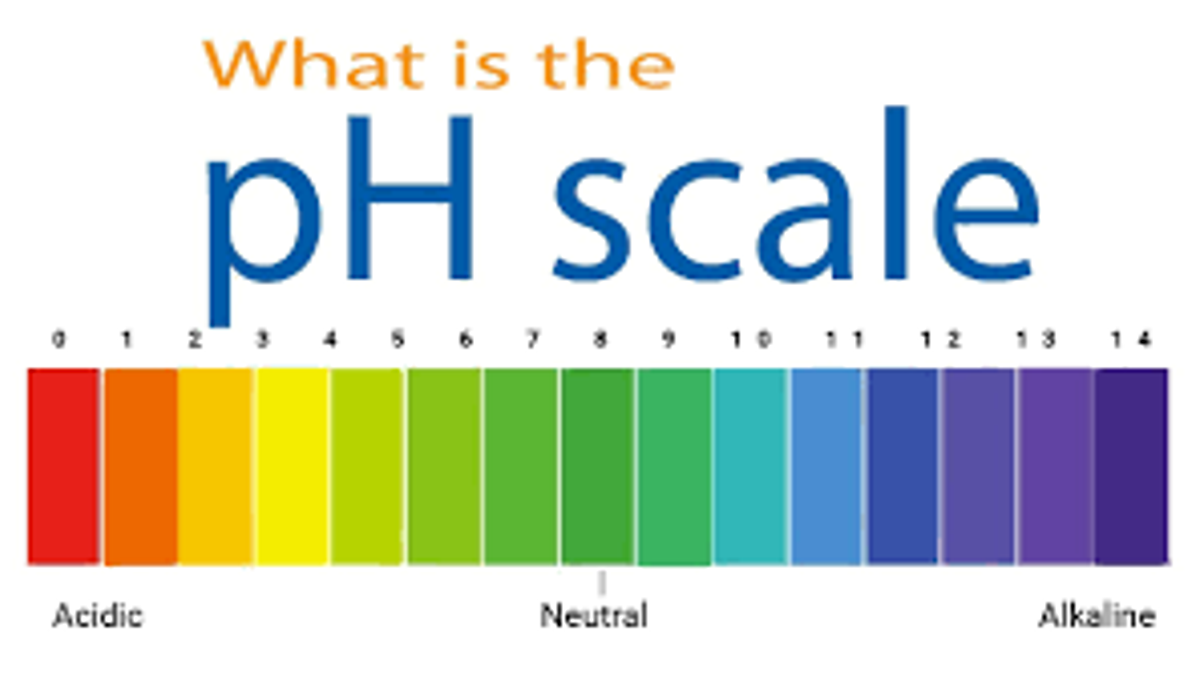

At its core, pH is a logarithmic scale used to specify the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. It quantifies the concentration of hydrogen ions ($H^+$). A pH of 7 is neutral, values below 7 are acidic, and values above 7 are alkaline (or basic). In biological contexts, maintaining a precise pH balance, known as homeostasis, is not merely advantageous; it is absolutely critical for life. Enzymes, the workhorses of biological reactions, have optimal pH ranges within which they function most efficiently. Deviations from these ranges can lead to denaturation, rendering the enzyme inactive and halting essential metabolic pathways. Protein structure, cell membrane integrity, nutrient transport, and even the genetic material within cells are all profoundly influenced by pH.

Enzyme Activity and Protein Conformation

Enzymes are proteins with complex three-dimensional structures that are exquisitely sensitive to their environment. The active site of an enzyme, where its substrate binds, is shaped by the arrangement of amino acid residues. These residues often carry charges that are dependent on the pH of the surrounding medium. At an optimal pH, these charges facilitate substrate binding and the catalytic process. However, as the pH deviates from the optimum, the charges on these amino acid residues can change, disrupting the enzyme’s structure and its ability to bind to its substrate, thereby reducing or eliminating its catalytic activity. This sensitivity is a primary reason why biological systems possess robust buffering mechanisms to maintain stable pH levels.

Cellular Integrity and Transport Mechanisms

Cell membranes, crucial for regulating the passage of substances into and out of cells, also rely on specific pH conditions. The lipid bilayer itself can be affected by extreme pH, but more importantly, the proteins embedded within the membrane – transporters, channels, and receptors – are highly pH-dependent. For instance, proton pumps, which actively move hydrogen ions across membranes, are fundamental to establishing pH gradients. These gradients are vital for processes like ATP synthesis in mitochondria and nutrient uptake in cells. Disruptions to these pH gradients, often caused by environmental changes or disease states, can compromise cellular function and viability.

Nucleic Acid Stability and Gene Expression

DNA and RNA, the molecules of heredity, are also indirectly affected by pH. While the phosphodiester backbone of nucleic acids is relatively stable across a range of physiological pH, changes can influence the ionization states of the bases, which can impact DNA replication, transcription, and translation. Furthermore, the proteins that interact with DNA to regulate gene expression, such as transcription factors and histones, are themselves subject to pH-dependent conformational changes. Therefore, maintaining cellular pH is crucial for the accurate transmission and expression of genetic information.

Technological Innovations in pH Measurement and Monitoring

The ability to accurately and precisely measure pH has been revolutionized by technological advancements, moving from rudimentary chemical indicators to sophisticated electronic sensors and automated systems. These innovations are not just about convenience; they are fundamental to our ability to study biological processes in real-time, across diverse environments, and at scales previously unimaginable.

The Evolution of pH Sensors

The cornerstone of pH measurement is the pH electrode. Early pH meters relied on glass electrodes, which, while revolutionary for their time, had limitations in terms of durability and response time. Modern pH sensing technologies have expanded significantly, incorporating:

Solid-State and ISFET Sensors

Ion-Selective Field-Effect Transistors (ISFETs) represent a significant leap forward. Unlike traditional glass electrodes that measure potential differences, ISFETs are semiconductor-based devices where the gate voltage is modulated by the concentration of specific ions, including hydrogen ions. This offers several advantages:

- Miniaturization: ISFETs can be manufactured at very small scales, enabling in-vivo monitoring and microfluidic applications.

- Durability: They are generally more robust and less prone to breakage than glass electrodes.

- Faster Response Times: ISFETs can provide rapid and stable readings.

- Reduced Electrolyte Drift: They often exhibit less drift compared to liquid-filled electrodes.

These advancements allow for continuous monitoring of pH within living organisms, in cell cultures, or in tiny biological samples, providing unprecedented insights into dynamic biological processes.

Optical pH Sensors

Optical pH sensing utilizes dyes or fluorescent probes that change their spectral properties (color or fluorescence intensity/wavelength) in response to pH variations. This approach offers unique advantages, particularly for applications where electrical interference is a concern or for remote sensing:

- Non-Electrochemical: Eliminates issues related to electrical noise and polarization.

- Remote Sensing: Can be integrated into fiber optics for measurements in inaccessible locations.

- Multiplexing: Different probes can be used simultaneously to measure pH and other parameters.

Recent innovations include the development of nanoparticles and nanocomposites embedded with pH-sensitive fluorophores, allowing for highly sensitive and targeted pH sensing within specific cellular compartments or tissues.

Automated and Remote Monitoring Systems

The ability to automatically and remotely monitor pH is crucial for a wide range of biological applications, from long-term ecological studies to clinical diagnostics.

Data Loggers and Telemetry

Modern pH sensors are frequently integrated with data loggers that continuously record measurements over extended periods. These loggers can store vast amounts of data, which can be retrieved manually or, increasingly, transmitted wirelessly via telemetry. This allows for:

- Continuous Environmental Monitoring: Tracking pH changes in aquatic ecosystems, soil, or agricultural settings over days, weeks, or even years.

- Real-time Clinical Data: Monitoring patient pH levels in intensive care units or during surgical procedures, alerting medical staff to critical changes.

- Autonomous Research Platforms: Deploying sensors on buoys, underwater vehicles, or even drones for in-situ data collection in remote or hazardous environments.

Microfluidics and Lab-on-a-Chip Devices

The convergence of microfluidics and pH sensing has led to the development of “lab-on-a-chip” devices. These miniaturized systems can perform complex biological analyses on tiny sample volumes. Integrated pH sensors on these chips allow for:

- High-Throughput Screening: Rapidly assessing the pH sensitivity of enzymes or drug candidates.

- Cellular Assays: Precisely controlling and monitoring the pH environment of individual cells or small cell populations.

- Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Developing portable devices for rapid pH testing in medical settings.

These technologies are transforming biological research by enabling more precise, efficient, and less invasive studies of pH-dependent phenomena.

pH in Applied Biological Technologies

The understanding and precise control of pH, empowered by technological innovation, are central to numerous applied biological technologies that impact human health, agriculture, and environmental sustainability.

Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Development

The biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries rely heavily on pH control for a multitude of processes.

Fermentation and Bioprocessing

Large-scale fermentation, used to produce antibiotics, enzymes, recombinant proteins, and biofuels, requires meticulous pH monitoring and control. Bioreactors are equipped with sophisticated pH probes and automated feedback systems that adjust the pH by adding acids or bases to maintain optimal conditions for microbial growth and product formation. This ensures consistent yields and high-quality products.

Drug Formulation and Delivery

The pH of pharmaceutical formulations can significantly impact drug stability, solubility, and bioavailability. Technologies for precise pH adjustment and stabilization are critical during drug development. Furthermore, advanced drug delivery systems, such as pH-sensitive liposomes or nanoparticles, are designed to release their therapeutic payload specifically in environments with a particular pH, such as acidic tumor microenvironments or the digestive tract, thereby improving efficacy and reducing side effects.

Environmental Monitoring and Restoration Technologies

Understanding and managing pH is crucial for assessing and improving the health of ecosystems.

Water Quality Monitoring

pH is a key indicator of water quality. Automated pH sensors deployed in rivers, lakes, and oceans provide continuous data on environmental conditions, helping to detect pollution, monitor the impact of acid rain, and assess the health of aquatic life. Data from these sensors can feed into sophisticated ecological models, informing conservation efforts and regulatory decisions.

Soil Health and Agriculture

Soil pH influences nutrient availability, microbial activity, and plant growth. Technologies for soil pH testing, ranging from simple field kits to advanced sensor arrays, help farmers optimize soil conditions for crop production. This includes selecting appropriate fertilizers and amendments, leading to increased yields and reduced environmental impact. Furthermore, precision agriculture technologies are integrating pH data with other environmental parameters to create optimized irrigation and fertilization strategies.

Medical Diagnostics and Therapeutics

The human body is a complex biochemical system where pH plays a vital role, and technological advancements are enhancing our ability to diagnose and treat pH-related imbalances.

Blood Gas Analysis

Accurate measurement of blood pH, along with partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide, is a cornerstone of critical care medicine. Advanced blood gas analyzers use electrochemical sensors to rapidly and precisely determine these parameters, providing essential information for managing patients with respiratory or metabolic disorders.

Gastrointestinal Health

pH varies dramatically throughout the gastrointestinal tract, and monitoring these changes can aid in diagnosing conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or malabsorption syndromes. Advances in wireless pH monitoring capsules allow patients to swallow a small device that transmits pH data from different sections of their digestive system, providing a non-invasive diagnostic tool.

The intricate dance of chemical reactions that define life is orchestrated by a delicate balance of pH. As our technological capabilities expand, so too does our ability to probe, understand, and harness the power of pH in biological systems. From the fundamental research laboratory to cutting-edge medical treatments and environmental stewardship, the intersection of pH and technology is a testament to human ingenuity, driving innovation across the vast and vital field of biology.