The term “seismically” is intrinsically linked to the study of earthquakes and seismic waves. When we talk about something happening “seismically,” we are referring to events or phenomena related to seismic activity. This encompasses not just the direct occurrences of earthquakes but also their causes, effects, and the methods used to detect and analyze them. Understanding seismic activity is crucial for hazard assessment, structural engineering, and scientific research into the Earth’s internal structure.

The Science of Seismic Activity

Seismic activity is the motion of the Earth’s surface resulting from the sudden release of energy in the Earth’s crust that creates seismic waves. This energy is most commonly released during earthquakes, but it can also be generated by volcanic eruptions, large landslides, and even human-made explosions. The study of these phenomena falls under the discipline of seismology.

Earthquakes: The Primary Source of Seismic Waves

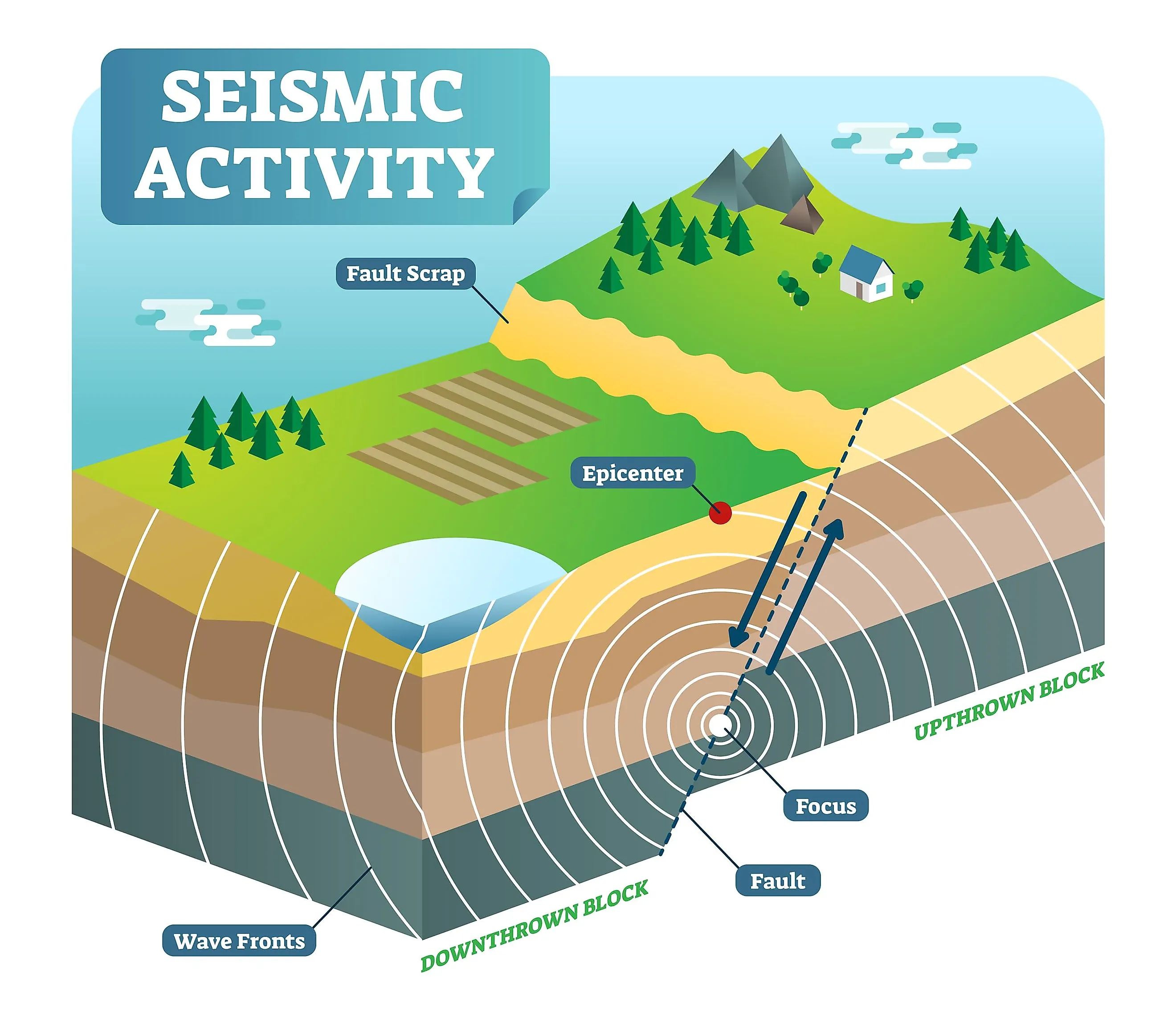

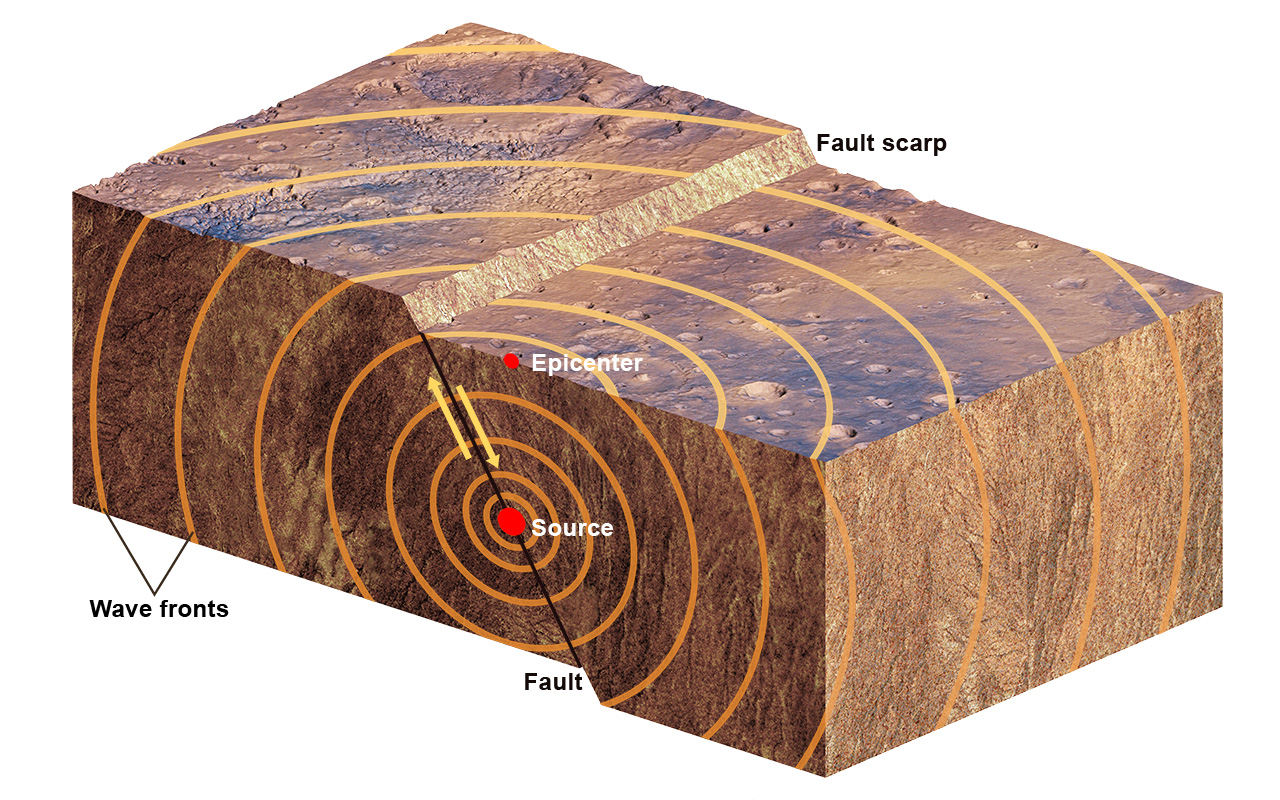

Earthquakes are the most significant and widely studied source of seismic activity. They occur when stress built up along fault lines in the Earth’s crust is suddenly released. This stress can accumulate over long periods due to the slow, continuous movement of tectonic plates. When the stress exceeds the strength of the rocks, they fracture, causing the ground to shake.

Tectonic Plates and Fault Lines

The Earth’s outermost layer, the lithosphere, is broken into several large pieces called tectonic plates. These plates are constantly in motion, driven by convection currents in the underlying mantle. The boundaries between these plates are where most earthquakes occur. Fault lines are fractures in the Earth’s crust where movement has taken place. These movements can be along strike-slip faults (where blocks move horizontally past each other), dip-slip faults (where blocks move up or down relative to each other), or oblique-slip faults, which involve a combination of both. The San Andreas Fault in California is a classic example of a strike-slip fault.

Types of Seismic Waves

When an earthquake occurs, energy is released in the form of seismic waves. These waves travel through the Earth and can be detected by seismographs. There are two main types of seismic waves: body waves and surface waves.

Body Waves: These waves travel through the Earth’s interior.

- P-waves (Primary Waves): These are compressional waves, meaning they cause particles in the rock to move back and forth in the same direction that the wave is traveling. P-waves are the fastest seismic waves and can travel through solids, liquids, and gases. They are often the first waves detected by seismographs, hence their name “primary.”

- S-waves (Secondary Waves): These are shear waves, meaning they cause particles in the rock to move perpendicular to the direction that the wave is traveling. S-waves are slower than P-waves and can only travel through solids. Their inability to pass through liquids is a key piece of evidence for the liquid outer core of the Earth.

Surface Waves: These waves travel along the Earth’s surface and are typically generated when body waves reach the surface. They are slower than body waves but often cause the most damage during an earthquake because they have larger amplitudes.

- Love Waves: These waves cause horizontal shearing of the ground. They are named after British mathematician A.E.H. Love.

- Rayleigh Waves: These waves cause particles in the ground to move in an elliptical motion, similar to waves on the surface of the ocean. They are named after Lord Rayleigh.

Other Sources of Seismic Activity

While earthquakes are the primary source, other geological and man-made events can also generate seismic waves.

Volcanic Eruptions

Volcanic eruptions involve the movement of magma beneath the Earth’s surface. This movement, along with the explosive release of gases and ash, can create seismic waves. Volcanic seismicity is often monitored to assess the potential for an eruption. The specific types of seismic signals generated by volcanoes can differ from those of tectonic earthquakes, often exhibiting volcanic tremor or long-period events.

Landslides and Avalanches

Large-scale landslides and avalanches, particularly those involving significant mass movement, can generate detectable seismic signals. The impact of the moving material on the ground creates vibrations that propagate as seismic waves. While usually localized, very large events can be registered by seismic networks.

Human-Induced Seismicity

Human activities can also induce seismic events.

- Explosions: Mining operations, quarrying, and nuclear testing create explosions that generate seismic waves. These are often distinguishable from natural earthquakes by their source characteristics.

- Reservoir Impoundment: The filling of large reservoirs behind dams can sometimes trigger small earthquakes. The immense weight of the water can stress pre-existing faults.

- Fluid Injection and Extraction: Activities like wastewater injection, hydraulic fracturing (fracking), and the extraction of oil and gas can alter subsurface pressures and potentially induce seismic events. This is an area of ongoing research and concern.

Detecting and Measuring Seismic Activity

The detection and measurement of seismic waves are fundamental to seismology. This is achieved through a sophisticated network of instruments and analysis techniques.

Seismographs and Seismometers

A seismograph is an instrument that records the ground motion caused by seismic waves. A seismometer is the actual sensor that detects the vibrations. Modern seismographs are highly sensitive and can detect even very small tremors. They typically consist of a mass suspended by a spring or pivot. When the ground moves, the inertia of the mass causes it to remain relatively still, while the casing of the instrument moves with the ground. This relative motion is then recorded.

Global Seismograph Networks

To effectively monitor seismic activity worldwide, numerous seismographs are deployed in a global network. These networks are operated by national geological surveys, universities, and international organizations. Data from these stations are shared to provide a comprehensive picture of seismic events. The density and distribution of seismographs are crucial for accurately locating the epicenter and determining the depth of earthquakes.

Seismograms and Data Analysis

The recording produced by a seismograph is called a seismogram. Seismograms are graphical representations of ground motion over time. Seismologists analyze seismograms to extract valuable information about seismic events.

Determining Location and Magnitude

By comparing the arrival times of P-waves and S-waves at different seismograph stations, seismologists can triangulate the location of an earthquake’s epicenter (the point on the Earth’s surface directly above the focus). The difference in arrival times directly correlates with the distance from the seismograph to the earthquake.

The magnitude of an earthquake is a measure of the energy released. The most common scale is the Richter scale, though the Moment Magnitude Scale (Mw) is now preferred by seismologists as it provides a more accurate measure of the total energy released. Magnitude is calculated based on the amplitude of the seismic waves recorded on seismograms, taking into account the distance from the epicenter.

Understanding Earth’s Interior

Seismic waves travel at different speeds through different materials. By studying how seismic waves refract and reflect as they pass through the Earth, seismologists can infer the composition and structure of the Earth’s interior, including the crust, mantle, and core. This is the primary method by which we understand what lies beneath our feet.

The Significance of Seismic Activity

Understanding seismic activity has profound implications for safety, infrastructure, and scientific discovery.

Hazard Assessment and Mitigation

One of the most critical applications of seismic study is in assessing seismic hazards. By analyzing historical seismic data, identifying active faults, and understanding regional seismicity patterns, scientists can create seismic hazard maps. These maps are crucial for:

- Building Codes: Informing the design and construction of buildings and infrastructure to withstand anticipated ground shaking. This includes specifying materials, structural reinforcement, and foundation design.

- Land-Use Planning: Guiding development away from high-risk areas and influencing zoning regulations.

- Emergency Preparedness: Developing effective emergency response plans, including evacuation routes, shelter locations, and communication strategies.

Earthquake Early Warning Systems

Advanced seismological techniques have led to the development of Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) systems. These systems detect the initial, faster-traveling P-waves of an earthquake and send out alerts before the slower, more damaging S-waves and surface waves arrive. This provides a few seconds to tens of seconds of warning, allowing people to take protective actions such as dropping, covering, and holding on, and can also automate safety measures like stopping trains or shutting down critical industrial processes.

Scientific Research and Exploration

Seismology plays a vital role in advancing our understanding of fundamental geological processes.

Plate Tectonics

The study of earthquakes provides direct evidence for the theory of plate tectonics, explaining the movement of continents, the formation of mountain ranges, and the distribution of volcanoes. Seismicity patterns at plate boundaries are key to understanding these large-scale geological forces.

Earth’s Dynamic Processes

Analyzing seismic waves allows scientists to peer deep into the Earth, revealing the dynamics of the mantle and the processes that drive plate movement. Understanding the composition and behavior of the Earth’s core is also heavily reliant on seismic wave behavior.

Predicting and Understanding Future Events

While predicting the exact time, location, and magnitude of future earthquakes remains a significant scientific challenge, ongoing research into seismic precursors, fault behavior, and stress accumulation aims to improve forecasting capabilities. Understanding the complex interplay of forces that lead to seismic events is crucial for this endeavor.

In conclusion, “seismically” is a term that encapsulates a vast and intricate field of scientific inquiry. It refers to anything related to the vibrations of the Earth’s crust, primarily caused by earthquakes, but also by other geological and human-induced events. The continuous monitoring, analysis, and understanding of seismic activity are paramount for protecting lives, safeguarding infrastructure, and deepening our knowledge of our dynamic planet.