The term “indexed” can appear in various contexts, and when discussing technology, particularly within the realms of data management, search engines, and advanced computational processes, it signifies a structured approach to information retrieval and organization. It’s a fundamental concept that underpins much of the digital world we interact with daily, enabling rapid access to vast amounts of data. In essence, an index is a meticulously organized system designed to speed up the process of finding specific information within a larger dataset. Without indexing, searching for a particular piece of data would be akin to sifting through an unorganized library, requiring a linear examination of every single item.

The Core Concept of Indexing: Creating Order from Chaos

At its heart, indexing is about creating a surrogate, a map, or a table of contents for a larger body of information. This surrogate allows systems to bypass the need to process the entire dataset when a specific query is made. Instead, the system consults the index, which points directly to the location of the desired information. This dramatically reduces search times, making data retrieval efficient and scalable. The effectiveness of an index hinges on its design and the principles it employs to represent the original data in a searchable format.

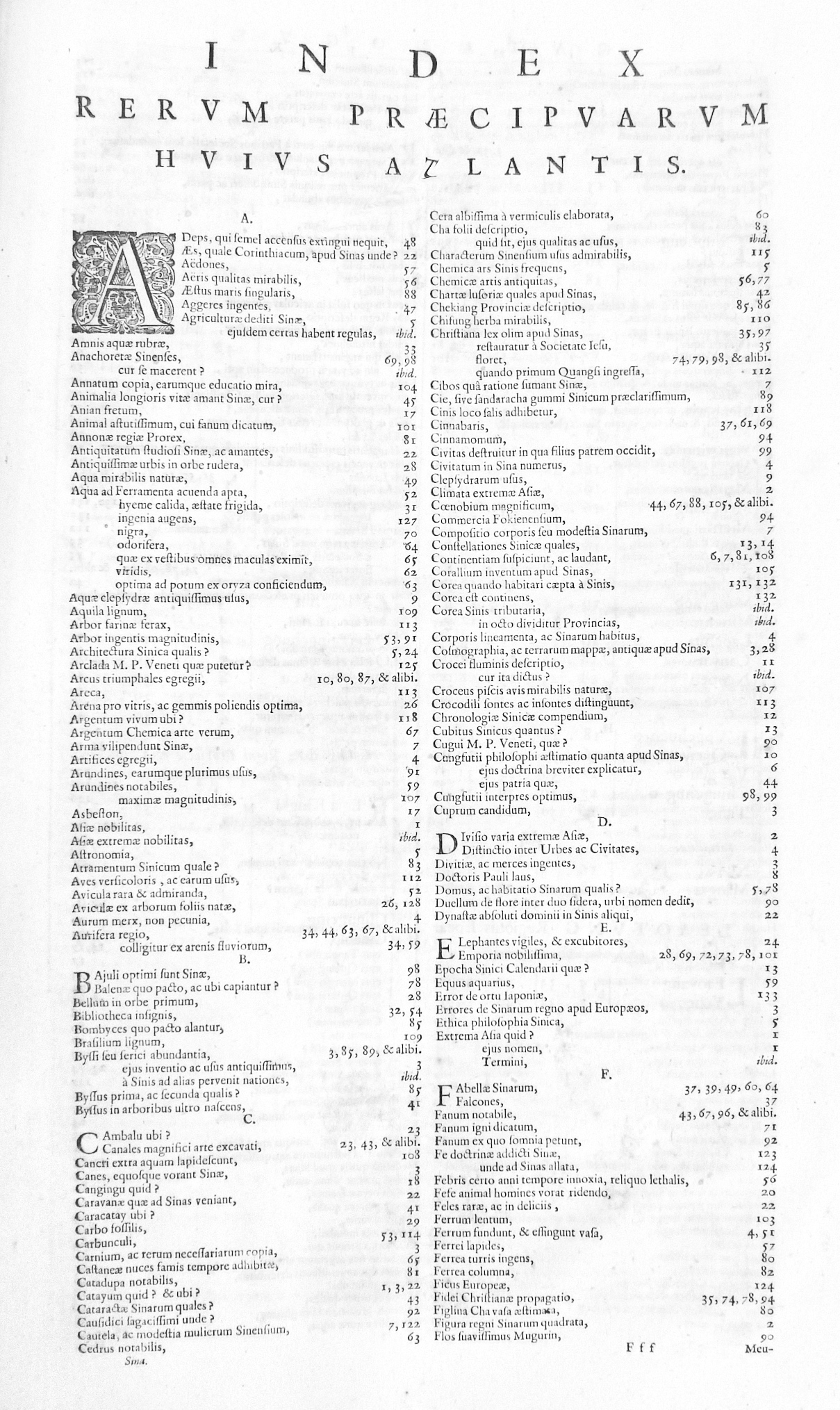

How Indices Work: A Bibliographic Analogy

To grasp the essence of indexing, consider the index found at the back of a book. This index lists keywords, concepts, or names mentioned within the text, along with the page numbers where they appear. If you want to find information about a specific topic, you don’t need to read the entire book. You consult the index, locate the relevant term, and are immediately directed to the pages containing that information. This is the fundamental principle behind digital indexing, albeit on a vastly larger and more complex scale. In digital systems, instead of page numbers, indices store pointers to data locations, often in the form of memory addresses or file paths.

The Importance of Structure and Efficiency

The primary driver behind indexing is efficiency. In an era where data is generated at an unprecedented rate, the ability to quickly access and process this data is paramount. Imagine a search engine trying to find relevant web pages for your query without an index. It would have to crawl and analyze every single web page on the internet every time you searched – an impossible task. Indexing allows search engines to pre-process and organize the web’s content, creating vast indices that can be queried in fractions of a second. This principle extends to databases, file systems, and many other data-intensive applications.

Types of Indices: Tailoring to Specific Needs

The way an index is constructed depends heavily on the type of data it’s indexing and the specific needs of the application. Different indexing strategies are employed to optimize for different kinds of queries and data structures. Understanding these variations helps to appreciate the sophistication of modern data management.

Database Indices: Optimizing Query Performance

In the realm of databases, indices are crucial for speeding up data retrieval operations. When you execute a SELECT query in a SQL database, for example, the database management system (DBMS) often utilizes indices to locate the requested rows without scanning the entire table.

B-Trees and B+ Trees: The Workhorses of Database Indexing

The most common types of database indices are B-trees and B+ trees. These are self-balancing tree data structures that maintain sorted data and allow for efficient searching, insertion, and deletion of records.

- B-trees: A B-tree is a generalized form of a binary search tree where each node can have more than two children. This structure is optimized for disk-based storage, minimizing the number of disk I/O operations required to find data. Internal nodes in a B-tree store keys and pointers to child nodes, while leaf nodes store the actual data records or pointers to them.

- B+ Trees: A B+ tree is a variation of a B-tree where all data records are stored exclusively in the leaf nodes. The internal nodes of a B+ tree only contain keys and pointers, facilitating faster traversal to the leaf nodes. Furthermore, the leaf nodes in a B+ tree are typically linked together in a sequential manner, allowing for efficient range queries (e.g., finding all records between two values). This makes B+ trees particularly well-suited for database indexing where sequential scanning of data is common.

Hash Indices: For Exact Match Queries

Hash indices are based on hash functions, which map data keys to specific locations within an index. They are highly efficient for exact match queries (e.g., finding a record with a specific ID). However, they are generally not suitable for range queries or sorting, as the hash function does not preserve the order of the keys.

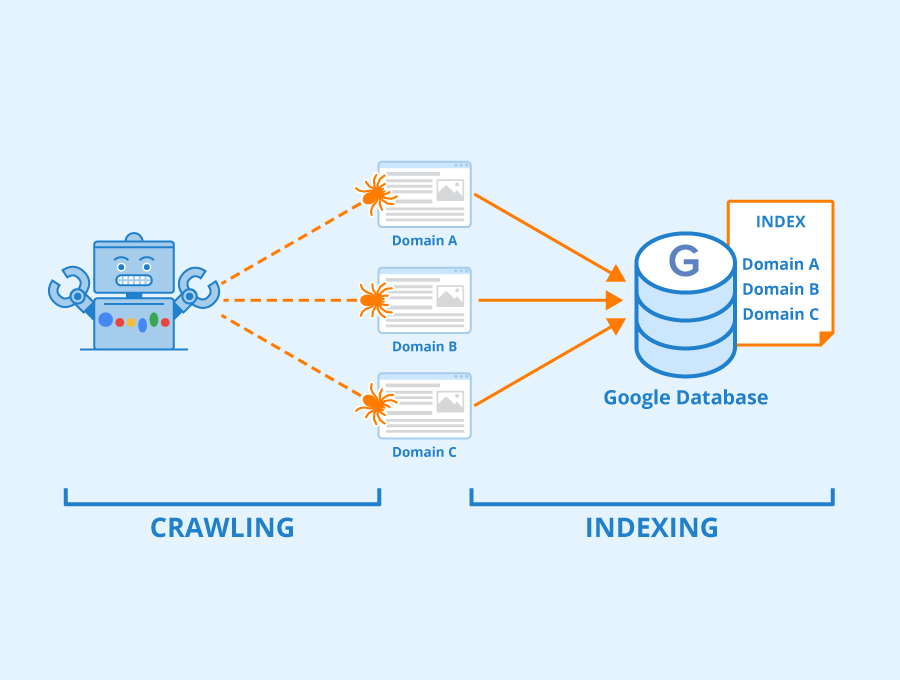

Search Engine Indices: Navigating the World Wide Web

Search engines like Google, Bing, and DuckDuckGo rely on massive, complex indices to provide search results. These indices are built by “crawling” the internet, where automated programs systematically visit web pages, extract their content, and store information about the pages and their terms.

Inverted Indices: The Backbone of Text Search

The primary indexing mechanism used by search engines is the inverted index. Unlike a traditional index that maps a document to the terms it contains, an inverted index maps terms to the documents in which they appear. For each word (or token) in a document collection, an inverted index stores a list of all the documents that contain that word, along with additional information such as the frequency of the word in each document and the positions of the word within those documents.

- Structure: An inverted index typically consists of a vocabulary (a list of all unique terms) and an inverted list for each term. The inverted list for a term contains entries for each document that includes the term. Each entry might include the document ID and positional information.

- Querying: When a user submits a search query, the search engine breaks the query into individual terms. It then looks up each term in its inverted index and retrieves the corresponding document lists. By intersecting or merging these lists based on the query’s logic (e.g., “AND,” “OR,” “NOT”), the search engine can quickly identify the documents that are most relevant to the query.

Beyond Keywords: Ranking and Relevance

Modern search engine indices go beyond simple term-to-document mapping. They incorporate sophisticated algorithms to rank the relevance of documents, considering factors like the frequency and placement of keywords, the authority and popularity of the website, and the user’s search history. This advanced indexing allows search engines to present the most useful results at the top of the search results page.

File System Indices: Organizing Your Digital Files

Even your operating system uses indices to manage the files and folders on your computer. When you search for a file on your hard drive, the operating system’s file system index helps to locate it quickly without having to scan every sector of the disk.

File System Metadata and Indexing Services

File systems store metadata about each file, such as its name, size, creation date, modification date, and location. Indexing services within the operating system build and maintain indices based on this metadata, allowing for fast searches based on various criteria. For example, you can search for all files modified in the last week, or all documents containing a specific word, by leveraging these indices.

Advanced Indexing Concepts and Applications

The concept of indexing extends beyond basic data retrieval and plays a critical role in more complex technological applications, driving innovation in fields like artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data analysis.

Full-Text Indexing: Comprehensive Information Retrieval

Full-text indexing is a specialized form of indexing that allows for searching within the content of documents, not just their metadata. This is particularly useful for large collections of text documents, such as articles, books, emails, or code.

Tokenization, Stemming, and Stop Words

Creating a full-text index involves several processing steps:

- Tokenization: Breaking down text into individual words or “tokens.”

- Stemming and Lemmatization: Reducing words to their root form (e.g., “running,” “ran,” “runs” all become “run”). This ensures that variations of a word are treated as the same.

- Stop Word Removal: Eliminating common words (like “the,” “a,” “is”) that have little semantic value for searching and can bloat the index.

These processed tokens are then used to build the inverted index, enabling powerful searches across the entire textual content.

Spatial and Temporal Indexing: Navigating Multi-Dimensional Data

As data becomes more complex, encompassing not only text but also geographical locations and time stamps, specialized indexing techniques emerge.

Geospatial Indices: Locating Data on a Map

Geospatial indices are designed to efficiently query data based on its spatial location. Techniques like Quadtrees and R-trees are used to organize spatial data, allowing for fast retrieval of objects within a given geographic area or proximity to a specific point. This is vital for applications like GPS navigation, mapping services, and location-based services.

Temporal Indices: Ordering Events Over Time

Temporal indices are optimized for queries involving time. They help in efficiently retrieving data based on time ranges or specific timestamps. This is crucial for analyzing time-series data, historical records, and event logs.

The Future of Indexing: AI and Machine Learning Integration

The evolution of indexing is increasingly intertwined with artificial intelligence and machine learning. As AI models become more sophisticated, they require efficient ways to access and process vast amounts of data for training and inference.

Vector Indices: Enabling Semantic Search

One of the most exciting developments is the rise of vector indices. In machine learning, data is often represented as numerical vectors (embeddings) that capture its semantic meaning. Vector indices (like Faiss, Annoy, or ScaNN) are designed to efficiently search for similar vectors within a high-dimensional space. This enables semantic search, where queries are understood based on their meaning rather than just keyword matching. For example, instead of searching for “red sports car,” a semantic search might return results for “crimson convertible” if the embeddings are sufficiently similar. This technology is transforming how we search for images, audio, and even complex concepts.

In conclusion, “indexed” is a fundamental concept that signifies a structured, organized, and optimized approach to managing and retrieving information. Whether it’s speeding up database queries, enabling rapid web searches, organizing your personal files, or powering advanced AI applications, indexing plays an indispensable role in the efficiency and functionality of modern technology. The continuous development of indexing techniques reflects the ever-growing volume and complexity of data we interact with, ensuring that we can find what we need, when we need it, with remarkable speed and accuracy.