The term “cleaved” in the context of technology, particularly in the realm of cameras and imaging, refers to the precise and intentional separation or division of an image, signal, or data stream. This act of cleaving is not about destruction or loss, but rather about segmentation for specific analytical, processing, or transmission purposes. Understanding what it means for an image or data to be cleaved is crucial for appreciating the sophisticated techniques employed in modern imaging systems, from advanced scientific instruments to consumer-grade cameras.

The concept of cleaving an image or data stream can be applied across a wide spectrum of applications within cameras and imaging. It often involves separating different layers of information, such as separating an object from its background, isolating specific spectral bands, or dividing a high-resolution image into smaller, more manageable tiles for processing. This segmentation allows for targeted operations, enhancing efficiency and enabling the extraction of nuanced details that might otherwise be lost in a monolithic data set.

Understanding Image Segmentation: The Core of “Cleaving”

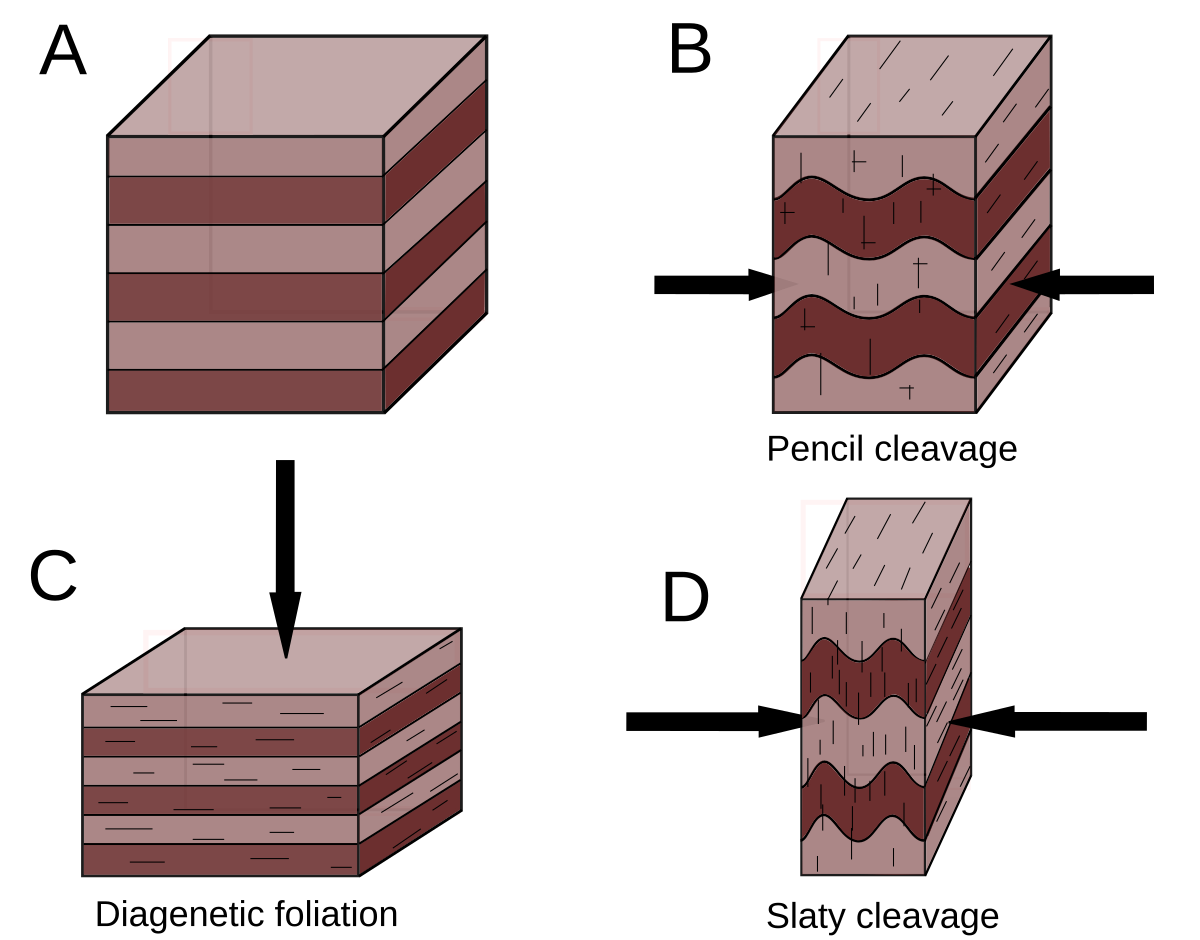

At its heart, “cleaving” in cameras and imaging is synonymous with image segmentation. This is the process of partitioning a digital image into multiple segments, often pixels. The goal is to simplify or change the representation of an image into something that is more meaningful and easier to analyze. In essence, cleaving an image means breaking it down into its constituent parts, where each part shares certain characteristics.

Pixels: The Fundamental Building Blocks of a Cleaved Image

Every digital image is ultimately composed of a grid of pixels. When we talk about cleaving an image at a fundamental level, we are referring to the ability to isolate and manipulate individual pixels or groups of pixels. Each pixel represents a single point in the image and carries information about its color and intensity. Advanced imaging systems can “cleave” an image by targeting specific pixels based on their properties, allowing for fine-grained analysis.

Object-Background Separation: Isolating the Subject

One of the most common and practical applications of cleaving in imaging is the separation of a foreground object from its background. This is a cornerstone of many image processing tasks, from photo editing to computer vision. In essence, the image is “cleaved” into two distinct regions: the object of interest and everything else. This allows the software or system to focus processing power and analytical attention solely on the subject.

- Techniques for Object-Background Separation:

- Thresholding: This is a simple but effective method where pixels are classified as either belonging to the object or the background based on a predefined intensity threshold. Pixels above the threshold might be considered part of the object, while those below are considered background.

- Edge Detection: Algorithms that identify sharp changes in intensity, which typically correspond to the boundaries of objects, can be used to “cleave” the image. By tracing these edges, the object can be delineated from the background.

- Clustering Algorithms: Techniques like K-means clustering can group pixels with similar color or intensity characteristics, effectively segmenting the image into different regions that can then be identified as object or background.

- Machine Learning Segmentation: More advanced methods utilize deep learning models, trained on vast datasets, to accurately identify and segment objects within complex scenes, even in challenging lighting conditions or with intricate details. These models can “cleave” images with remarkable precision.

Semantic and Instance Segmentation: Adding Meaning to the Cleave

Beyond simply separating an object from its background, more sophisticated forms of cleaving involve understanding the “meaning” of the segmented regions.

- Semantic Segmentation: This involves assigning a class label to every pixel in an image. For instance, in a scene captured by a drone, semantic segmentation could cleave the image into regions representing “road,” “tree,” “building,” and “sky.” Each pixel within a “tree” region would be labeled as such, regardless of whether it’s part of a single tree or multiple trees.

- Instance Segmentation: This is an even more granular form of cleaving. It not only assigns a class label to each pixel but also distinguishes between different instances of the same class. So, in the drone example, instance segmentation would not only identify “trees” but also differentiate between “tree 1,” “tree 2,” and so on. This level of cleaving is critical for tasks requiring precise object counting and individual object tracking.

Spectral and Data Layer Cleaving: Unveiling Hidden Information

The concept of cleaving extends beyond the visible light spectrum and simple spatial divisions. In advanced imaging, data is often captured and processed in layers, and cleaving these layers unlocks a deeper understanding of the subject.

Multispectral and Hyperspectral Imaging: Cleaving by Wavelength

Multispectral and hyperspectral cameras capture images across numerous narrow, contiguous spectral bands, far beyond the three broad bands (red, green, blue) of a standard RGB camera. This allows for the “cleaving” of the image based on its spectral properties.

- Multispectral Imaging: These cameras typically capture data in 3 to 15 spectral bands. By cleaving the captured data into these individual bands, we can analyze the unique spectral signatures of different materials. For example, in agriculture, cleaving multispectral data can reveal the health of crops by analyzing their reflection of near-infrared light, which is strongly influenced by chlorophyll content.

- Hyperspectral Imaging: This technology captures hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands. This provides an incredibly rich dataset, allowing for highly detailed spectral analysis. Cleaving hyperspectral data enables the identification of specific minerals, chemicals, or even subtle variations in the composition of materials that would be invisible to the naked eye or standard cameras. This is invaluable in fields like remote sensing, material science, and medical diagnostics.

Depth Information: Cleaving the Scene in Three Dimensions

Many modern cameras and imaging systems can capture depth information, essentially creating a 3D map of the scene. This depth data can be “cleaved” from the visual image or processed independently.

- Stereoscopic Vision: Similar to human binocular vision, stereoscopic cameras capture two images from slightly different viewpoints. By comparing these two images, depth information can be calculated, effectively “cleaving” the scene into layers of distance.

- LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging): LiDAR systems emit laser pulses and measure the time it takes for them to return after reflecting off surfaces. This process generates a dense point cloud, where each point has X, Y, and Z coordinates. This point cloud can be thought of as a “cleaved” representation of the 3D structure of the environment, independent of visual appearance.

- Time-of-Flight (ToF) Sensors: These sensors also measure the time it takes for light to travel to an object and back, providing depth information. This data can be “cleaved” from RGB data or used to create depth maps for applications like augmented reality or robotics.

Practical Applications of Cleaving in Camera Technology

The ability to “cleave” images and data streams has profound implications across numerous industries, driving innovation and enabling new capabilities.

Enhanced Object Recognition and Tracking

The precise segmentation and isolation of objects through cleaving are fundamental to robust object recognition and tracking systems.

- Autonomous Vehicles: For self-driving cars, cleaving is essential for identifying pedestrians, other vehicles, traffic signs, and lane markings. This allows the vehicle to understand its environment and make informed driving decisions.

- Surveillance and Security: Cleaving enables security systems to isolate individuals or suspicious objects within a video feed, triggering alerts or initiating further analysis.

- Industrial Automation: In manufacturing, cleaving can be used to identify and track products on an assembly line, ensuring quality control and efficient workflow.

Advanced Image Editing and Manipulation

For photographers and videographers, the concept of cleaving is deeply intertwined with their creative tools.

- Masking and Layering: Professional photo editing software heavily relies on the ability to “cleave” parts of an image using masks. This allows users to selectively apply adjustments, filters, or effects to specific areas without affecting the rest of the image.

- Background Removal: A common application of cleaving is the seamless removal of backgrounds from portraits or product shots, allowing them to be placed on new backgrounds.

- Compositing: In filmmaking and visual effects, cleaving and then reassembling different image elements are crucial for creating realistic or fantastical scenes.

Scientific and Medical Imaging

The ability to cleave data is revolutionizing scientific research and medical diagnostics.

- Microscopy: In microscopy, cleaving can be used to isolate specific cells, organelles, or molecular structures for detailed analysis. Hyperspectral microscopy, for example, cleaves spectral information to identify cellular components.

- Medical Imaging (MRI, CT Scans): These imaging modalities generate vast amounts of data that are often “cleaved” into anatomical slices or regions of interest for diagnosis and treatment planning. Segmentation algorithms are vital for identifying tumors, lesions, or other abnormalities.

- Remote Sensing: As mentioned earlier, cleaving spectral bands from satellite and aerial imagery is fundamental for analyzing land use, monitoring environmental changes, and identifying resources.

The Future of Cleaving in Imaging

As camera technology continues to advance, the concept of cleaving will become even more sophisticated and integrated.

Real-time AI-Powered Segmentation

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is enabling real-time, highly accurate segmentation. Cameras will be able to “cleave” complex scenes and identify objects with unprecedented speed and precision directly at the point of capture.

Dynamic Data Stream Cleaving

Instead of just static images, future systems will be able to dynamically cleave and process continuous streams of data, adapting to changing environments and priorities. This is crucial for applications like autonomous navigation and advanced robotics.

Personalized Imaging Experiences

Cleaving could also lead to more personalized imaging experiences. Imagine a camera that automatically “cleaves” the most important subjects in a scene and optimizes its settings to capture them perfectly, or a system that cleaves only the relevant information for a specific user’s needs.

In conclusion, while the term “cleaved” might sound somewhat abstract, in the context of cameras and imaging, it represents a fundamental and powerful concept: the intelligent segmentation and isolation of image data. From the basic division of pixels to the complex separation of spectral bands and 3D structures, cleaving empowers us to extract more meaning, enhance analysis, and unlock new creative and scientific possibilities. As technology progresses, the ways in which we cleave and understand visual information will only continue to expand, pushing the boundaries of what is possible with cameras and imaging systems.