In the realm of physical activity, the term “intensity” is a cornerstone concept, often discussed but sometimes vaguely understood. It’s the driving force behind our workouts, dictating their effectiveness and our physiological responses. Understanding what constitutes exercise intensity is crucial for anyone looking to optimize their fitness, achieve specific goals, or simply engage in exercise safely and productively. This article delves into the multifaceted nature of exercise intensity, exploring how it’s measured, its physiological impact, and how to manipulate it to suit individual needs.

The Physiology of Intensity: How Your Body Responds

Exercise intensity isn’t just an abstract measurement; it’s a direct reflection of the physiological demands placed upon your body. When you exercise, your body mobilizes various systems to meet the increased energy requirements. The harder you work, the more these systems are challenged.

Cardiovascular and Respiratory Demands

The most immediate and noticeable impact of increased exercise intensity is on your cardiovascular and respiratory systems. As your muscles demand more oxygen and nutrients to fuel their activity, your heart rate increases to pump blood more efficiently. This elevated heart rate delivers oxygenated blood to working muscles and removes metabolic byproducts like carbon dioxide.

Simultaneously, your respiratory rate and depth of breathing increase to facilitate greater oxygen intake and carbon dioxide expulsion. The rate at which your body can deliver oxygen to and remove waste from working tissues is known as your aerobic capacity, often measured by VO2 max. Higher intensity exercise pushes your aerobic system closer to its limits, demanding a greater VO2 max. The anaerobic threshold is another critical physiological marker related to intensity. This is the point during exercise where the body begins to rely more heavily on anaerobic energy production, leading to the buildup of lactic acid. Working above your anaerobic threshold is characteristic of high-intensity exercise and can only be sustained for shorter periods.

Muscular Engagement and Energy Systems

Beyond the cardiovascular system, exercise intensity directly influences the way your muscles are recruited and the energy pathways they utilize.

Muscle Fiber Recruitment

Different types of muscle fibers are recruited depending on the intensity and duration of the exercise. Slow-twitch (Type I) muscle fibers are fatigue-resistant and are primarily used for endurance activities and lower-intensity efforts. As intensity increases, fast-twitch (Type IIa and Type IIx) muscle fibers are recruited. Type IIa fibers are a hybrid, capable of both aerobic and anaerobic energy production, while Type IIx fibers are primarily anaerobic and powerful but fatigue very quickly. High-intensity workouts, therefore, engage a greater proportion of these powerful, fast-twitch fibers.

Energy Substrate Utilization

The primary fuel source for your muscles also shifts with intensity. At lower intensities, your body primarily relies on fat as an energy substrate, as this process is slower but sustainable for long periods. As intensity increases, the body shifts towards using carbohydrates (glycogen) stored in your muscles and liver. Carbohydrates can be broken down more rapidly to produce ATP, the energy currency of cells, allowing for higher power output. During very high-intensity efforts that are anaerobic in nature, the body exclusively relies on carbohydrate breakdown for rapid ATP production.

Measuring Exercise Intensity: Objective and Subjective Approaches

Accurately gauging exercise intensity is fundamental to tailoring workouts for specific goals, whether it’s improving cardiovascular health, building strength, or enhancing endurance. Fortunately, a variety of methods exist, ranging from objective, quantifiable metrics to more subjective, perceived measures.

Objective Measures: Heart Rate and Metabolic Equivalents (METs)

Objective measures provide concrete data that can be used to track progress and ensure you’re exercising within the desired intensity zones.

Heart Rate Monitoring

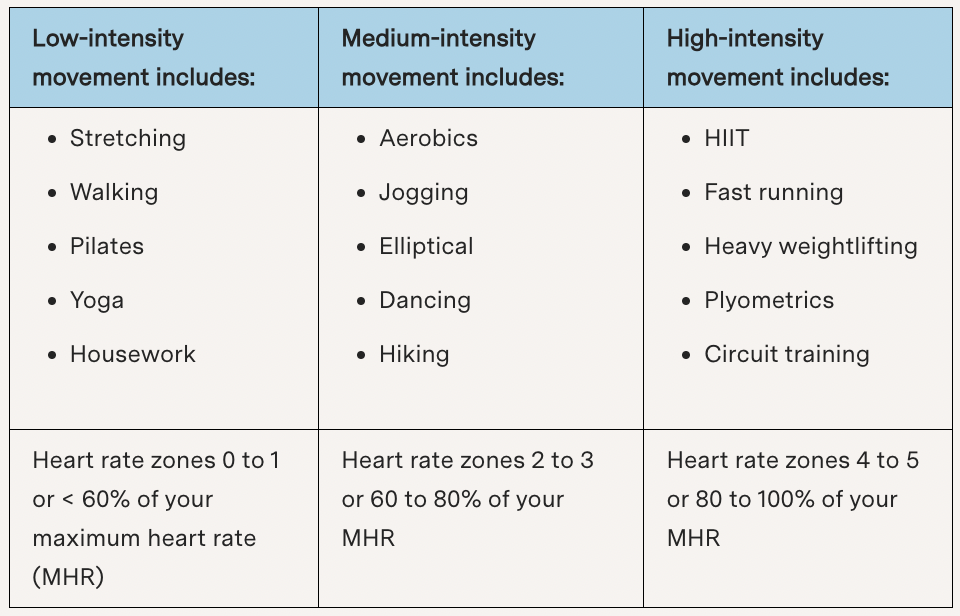

Heart rate is one of the most accessible and widely used objective measures of exercise intensity. Your maximum heart rate (MHR), often estimated by the formula 220 minus your age, serves as a benchmark. Exercise intensity can then be expressed as a percentage of your MHR. For example:

- Low Intensity: 50-60% of MHR

- Moderate Intensity: 60-70% of MHR

- Vigorous/High Intensity: 70-85% of MHR

Modern fitness trackers and heart rate monitors make this measurement seamless, displaying your heart rate in real-time and often classifying it into intensity zones. However, it’s important to note that MHR estimations are not universally accurate, and individual variations exist.

Metabolic Equivalents (METs)

Metabolic Equivalents (METs) offer another objective way to quantify exercise intensity. One MET is defined as the energy expenditure of sitting quietly. Different physical activities are assigned MET values based on their typical energy cost.

- Light Activity: < 3.0 METs (e.g., slow walking, light household chores)

- Moderate Activity: 3.0-6.0 METs (e.g., brisk walking, cycling at a moderate pace, gardening)

- Vigorous Activity: > 6.0 METs (e.g., running, swimming laps, high-intensity interval training)

METs provide a standardized way to compare the energy expenditure of various activities, regardless of an individual’s fitness level. For instance, running at 6 mph is approximately 10 METs, indicating a vigorous intensity.

Subjective Measures: Perceived Exertion

While objective measures offer precision, subjective measures provide a personal and often intuitive understanding of intensity, especially when objective tools are unavailable or when considering factors like stress, fatigue, and sleep.

The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale

The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale is a widely used and validated subjective tool. It asks individuals to rate how hard they feel they are working on a scale, typically from 6 to 20, or a modified version from 0 to 10. The original scale (6-20) is designed to correlate with heart rate (multiplying the RPE score by 10 approximates heart rate).

- 6-7: Very, very light (no exertion)

- 8-9: Very light

- 10-11: Fairly light

- 12-13: Moderate

- 14-15: Somewhat hard

- 16-17: Very hard

- 18-19: Very, very hard

- 20: Maximal exertion

The RPE scale encourages individuals to consider their overall bodily sensations, including breathing rate, heart rate, muscle fatigue, and sweat production. It’s a valuable tool for self-monitoring and adjusting workout intensity on the fly. A modified scale (0-10) is often used for its simplicity: 0 for no exertion, 5 for moderate exertion, and 10 for maximal exertion.

The Talk Test

The Talk Test is a simple, practical, and accessible method for gauging exercise intensity without any equipment. It relies on your ability to hold a conversation during physical activity.

- Low Intensity: You can talk easily, sing even.

- Moderate Intensity: You can talk, but not sing. You might be slightly breathless.

- High Intensity: You can only speak a few words at a time before needing to pause for breath.

The Talk Test is particularly useful for beginners or those who prefer a less technical approach to understanding their effort level. It aligns well with the physiological responses: at low intensity, breathing is minimal; at moderate intensity, breathing is noticeable but allows for conversation; and at high intensity, breathing is significantly elevated, making prolonged speech difficult.

Manipulating Intensity for Diverse Fitness Goals

The ability to effectively manipulate exercise intensity is paramount to achieving a broad spectrum of fitness objectives. Whether the goal is to build cardiovascular endurance, enhance muscular strength, lose weight, or improve athletic performance, strategically adjusting intensity plays a pivotal role.

Cardiovascular Endurance and Fat Loss

For individuals aiming to improve their cardiovascular endurance and promote fat loss, a combination of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and periods of higher intensity is often recommended.

- Moderate-Intensity Aerobic Exercise: Sustained periods (e.g., 30-60 minutes) of moderate-intensity exercise, typically between 60-70% of MHR or an RPE of 12-14, are highly effective for building aerobic capacity and improving the body’s ability to utilize fat as an energy source. The sustained effort promotes adaptations in the cardiovascular system, making it more efficient at delivering oxygen.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): Incorporating HIIT, which involves short bursts of very high-intensity exercise (e.g., 80-95% of MHR, RPE 16-19) followed by brief recovery periods, can significantly boost cardiovascular fitness and metabolic rate. HIIT is known for its “afterburn effect” (Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption or EPOC), where the body continues to burn calories at an elevated rate long after the workout has ended. While HIIT sessions are typically shorter, their intensity demands a higher level of physiological adaptation.

The synergy between moderate and high-intensity training can lead to more significant improvements in VO2 max and a greater overall calorie expenditure, contributing to effective fat loss and improved cardiovascular health.

Strength Training and Muscle Hypertrophy

When the primary goal is to build strength and muscle mass (hypertrophy), intensity is typically dictated by the weight lifted and the number of repetitions performed.

- Heavy Lifting for Strength: To maximize strength gains, exercises are generally performed with heavier weights that allow for fewer repetitions (e.g., 1-6 repetitions per set) at an intensity that makes completing the last repetition very challenging. This forces the muscles to recruit a higher proportion of fast-twitch muscle fibers and stimulates neural adaptations that enhance the ability to generate force.

- Moderate to High Reps for Hypertrophy: For muscle growth, moderate to high repetitions (e.g., 8-15 repetitions per set) are often employed, using weights that allow for progressive overload. The intensity is such that the last few repetitions of each set are difficult to complete with good form. This range creates significant metabolic stress and mechanical tension within the muscle fibers, leading to cellular damage that, with proper recovery and nutrition, results in muscle hypertrophy.

Understanding the relationship between weight, repetitions, and perceived exertion is key in strength training. An RPE of 7-9 on a scale of 1-10 is often targeted for hypertrophy training, indicating a challenging but manageable effort for the target rep range.

Considerations for Different Populations

The appropriate intensity of exercise is not a one-size-fits-all concept. It must be individualized based on factors such as age, current fitness level, medical history, and specific goals.

Beginners and Deconditioned Individuals

For individuals new to exercise or those returning after a period of inactivity, starting with low to moderate intensity is crucial. This allows the body to gradually adapt to the demands of physical activity, reducing the risk of injury and overexertion. Focusing on proper form and building consistency with lower intensities will lay a solid foundation for future progression. The talk test is an excellent tool for this population, ensuring they can maintain conversation and avoid excessive breathlessness.

Advanced Athletes and Elite Performers

Advanced athletes and elite performers often incorporate a wider spectrum of intensities, including very high-intensity work and anaerobic conditioning, to push their physiological limits and optimize performance. However, even at this level, strategic periodization and recovery are essential to prevent overtraining and maintain long-term progress. Their programming often involves precisely calibrated intensity zones, determined through performance testing and physiological monitoring.

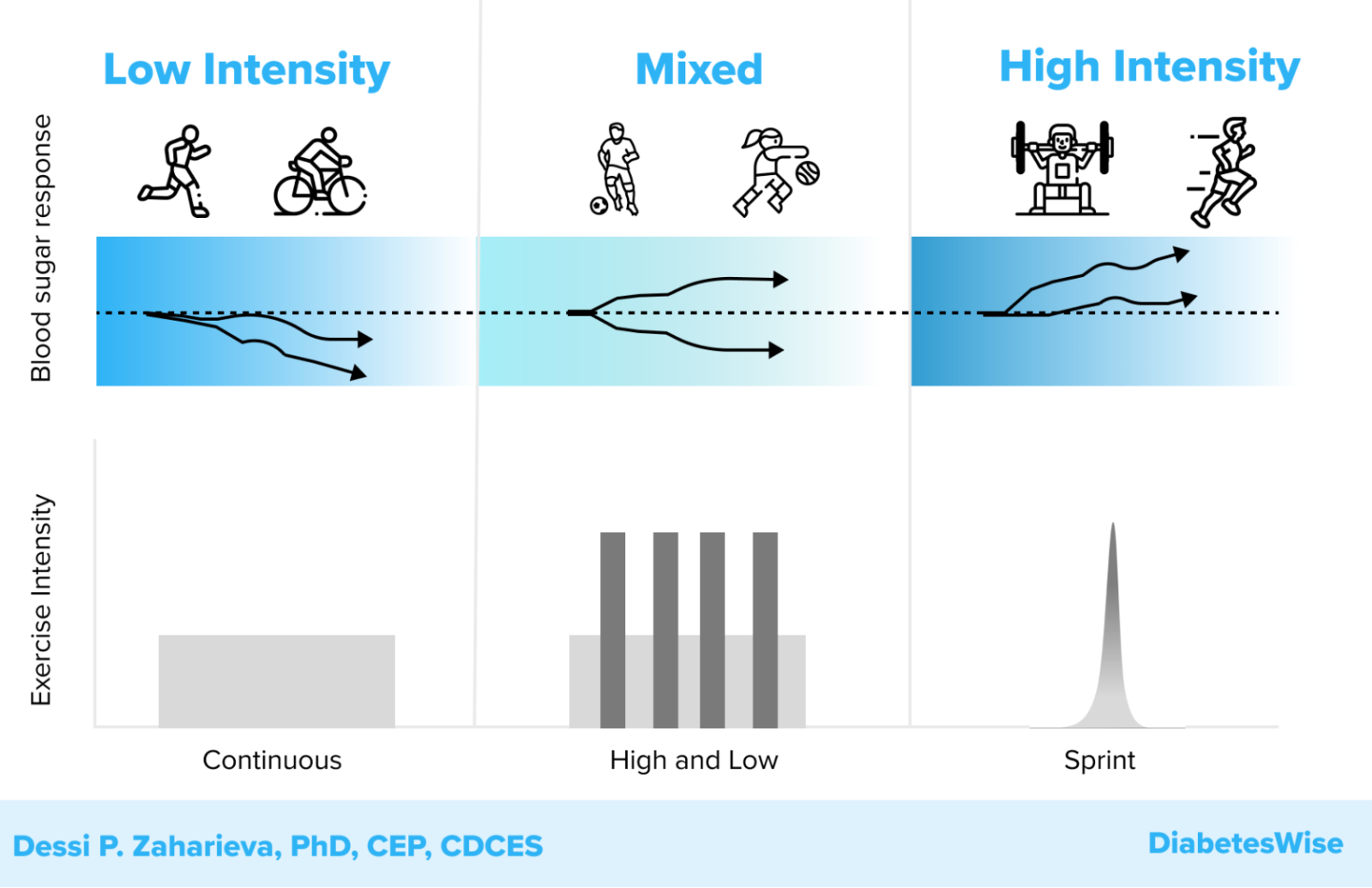

Individuals with Chronic Conditions

For individuals managing chronic health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or arthritis, exercise intensity must be carefully prescribed and monitored by a healthcare professional or a qualified exercise physiologist. Moderate-intensity exercise is often recommended to improve cardiovascular health, manage blood glucose levels, and reduce pain, but the specific intensity, duration, and type of exercise will be highly individualized to ensure safety and efficacy.

In conclusion, understanding and applying the principles of exercise intensity is fundamental to unlocking the full benefits of physical activity. By employing a combination of objective and subjective measures, and by strategically manipulating intensity, individuals can tailor their workouts to meet their unique fitness goals, leading to improved health, performance, and overall well-being.